CHAPTER 107 Sacroiliac Disease

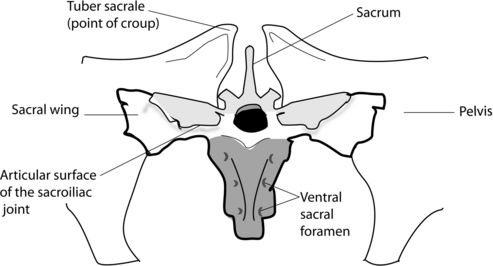

The skeletal structures involved in sacroiliac disease include the pelvic bones, vertebral column, and sacroiliac joints where the ventral aspect of the ilium, the ilial wing, comes into close contact with the sacral bone (Figure 107-1). At this junction there are two synovial joints, with a thin layer of fibrocartilage at the ilial facets and hyaline cartilage at the sacral facets.

Figure 107-1 Bony structures of the sacroiliac region of the horse (viewed from the front of the horse).

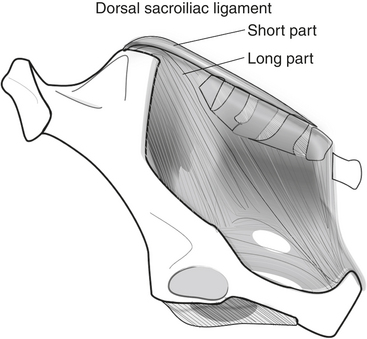

At the ventral aspect of the sacroiliac joint, several ligamentous structures provide support, including the capsule of the joint itself and a package of small fibrous ligaments known as the ventral sacral ligaments. Also some ligaments originating from the sacral bone attach muscles to the great trochanter of the femur. On the top of the pelvic bones, the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments originate from the tuber sacrale. These include a long part, which adheres to the fibrous structures of the pelvis (the sciatic ligament), and a smaller, short part that adheres to the sacral bone and the coccygeal vertebrae and ligaments (Figure 107-2). Also, from the ventral aspect of the ilial wing, the interosseus sacroiliac ligament supports the sacroiliac joint.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

History

Horses with sacroiliac pain may be presented with a great diversity of owner or rider complaints, including reduced stride length in one or both hind limbs, asymmetry of the hind end with one hip lowered, or atrophy of the croup muscles. Owners report changes in both the rhythm and quality of the walk, with a more lateral element to the walk seen especially during serpentines or circles. Reduced stride length may be seen in one or both hind limbs. There are no clear signs at the trot, just a little stiffness with slightly reduced propulsion and engagement. Downward transitions from canter to trot or from trot to walk can be of lower quality, with a disturbance in the rhythm in the new gait in the first strides after the transition. Going downhill, even when the incline is small, can be difficult, and refusal to jump in hunting, cross-country, or eventing is a common rider complaint.