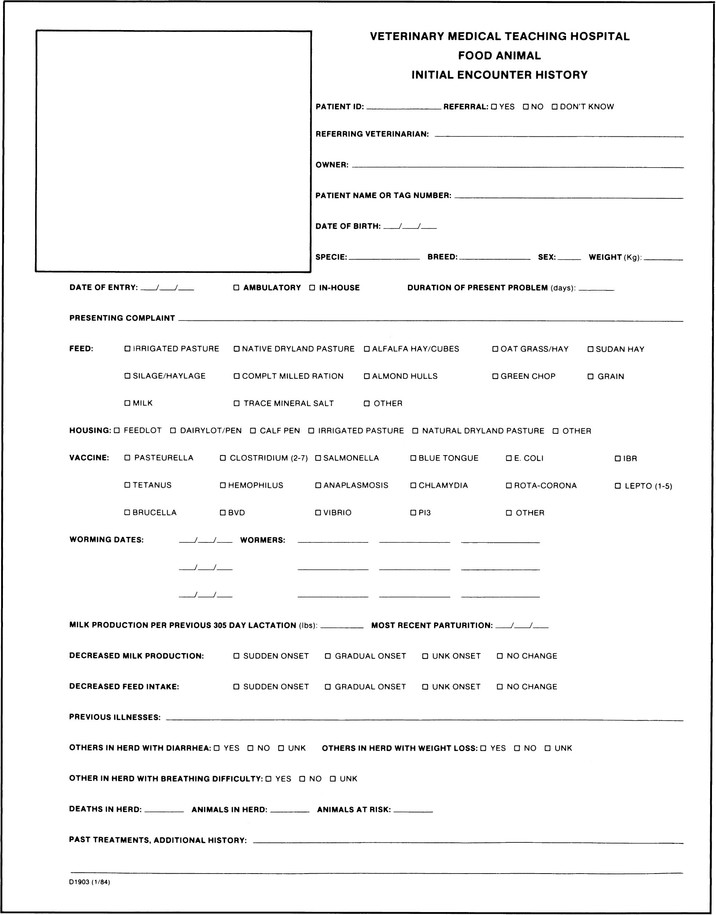

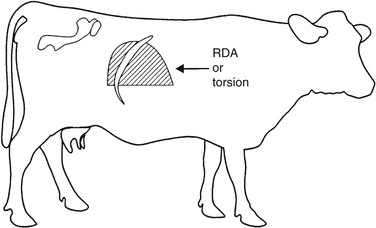

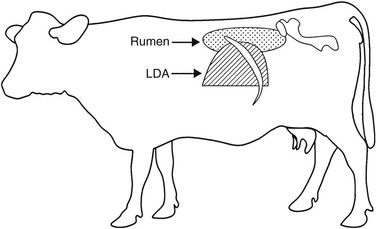

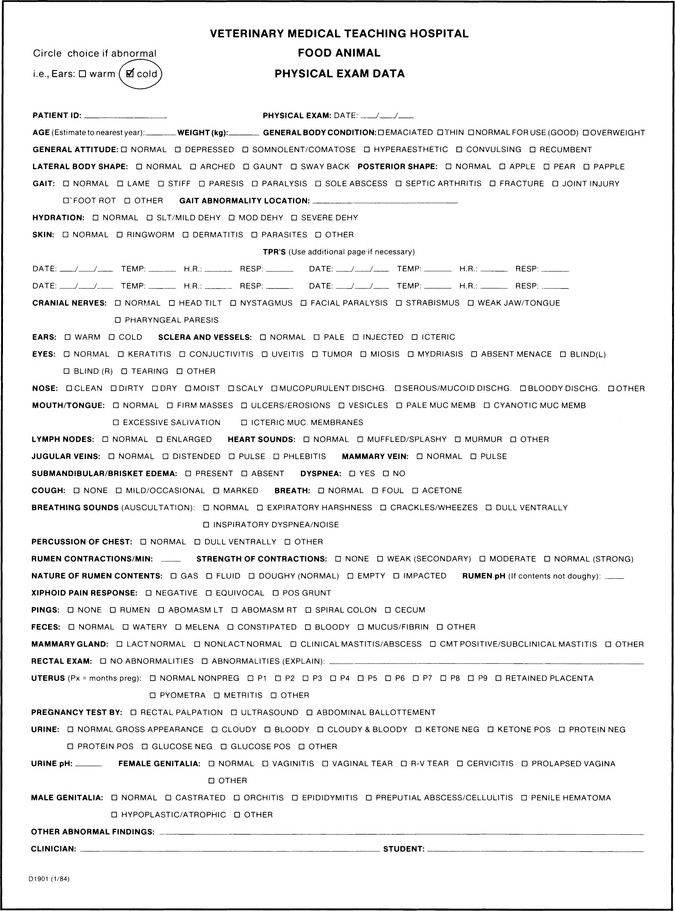

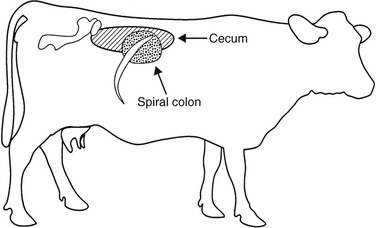

Ronald L. Terra, Consulting Editor James P. Reynolds The initial and often the most important step in the diagnostic approach to the sick ruminant is the physical examination. Before or perhaps throughout this process an anamnesis is obtained by asking questions of the owner or manager. The signalment can be derived by either observation or questioning the owner, and information related to the chief, or presenting, complaint should be determined, especially the duration, whether the onset was gradual or sudden, and any associated signs that may have been noted. For females, one must know when the last parturition occurred, and for dairy cows, what the production parameters were in the previous lactation, as well as in the current lactation. With dairy cows a drop in milk production is often the only sign noted by the owner. Weight can be either approximated, via heart-girth measurements, or determined exactly if facilities exist. What and how the animal is fed are questions to be asked. Does the animal refuse any or all of the feed offered? Is there more than one ration or feeding regimen for this particular operation? If so, are these same signs noted in animals exposed to different feeding practices? The examiner also obtains vaccination and worming history and inquires about pasture or housing practices to determine the influence that management factors have on the incidence of the disease. Previous diseases noted in the herd, therapeutic regimens used, and resolutions of previous problems are pertinent aspects. Finally, the examiner should note the treatment history of the patient. An example of a history questionnaire that can be used for ruminants is included (Fig. 1-1). Specific problems that are noted in the history or physical examination can be looked up on pages 21 and 22, and lists of differential diagnoses can be considered. A complete examination should always be performed even if the presenting complaint is easily recognizable. The physical examination provides the veterinarian with information that is used to assess the health status of the patient. This information, combined with that obtained while taking the history, enables the practitioner to determine which specific signs of disease are present (i.e., what the problem(s) is/are) and aids in the localization of the disease process to specific organ systems. The physical examination also helps to determine which ancillary diagnostic tests must be performed. Additional information gathered during the examination may reveal disorders other than the presenting complaint that warrant further attention and may have a profound influence on the prognosis of the case. Realistically, economic and temporal constraints preclude full examinations in some cases. In these situations the veterinarian must be familiar enough with the complete physical examination to know which aspects can be excluded and which should be performed. A systematic approach to the animal must be developed and used in every physical examination. The first step is to form an initial overall impression by observing the animal from a distance. The animal is then restrained and examined topographically, beginning on one side, moving to the other, and then evaluating the rear and finally the head and neck. Thus individual organs and systems are examined completely, although disjointedly, and the information gained is correlated to form the complete diagnosis. As observations are made and a physical examination is performed, it is important to follow a systematic approach and to record findings. A checklist has been found to be extremely useful (Fig. 1-2). While observing the animal from a distance, the examiner should assess its posture, gait, behavior, and physical condition. Observation of the other members of the flock or herd helps to differentiate normal from abnormal characteristics under each particular management system because normal may vary from farm to farm and because what is considered “normal” for a farm by the owner or herdsman might actually be abnormal; this information is valuable for assessing the incidence of a disease or disorder that is caused by management. As more animals in more herds are observed, a background of knowledge is gained, allowing the practitioner to assess these management deficiencies more reliably. The general appearance and conformation of the animal are included in determining posture. These are assessed in light of the age and breed of the patient. Determining abnormalities in posture can be difficult; however, noting these subtle changes can contribute greatly to the diagnosis of a disease process. Conformation is recognized by looking at the overall size and shape with particular regard to height, width, and relationship of the head, neck, and legs to the trunk. The general appearance of the patient in light of overall conformation can then be assessed. Determining a body condition score and correlating it with stage of lactation can offer insight into the course of the presenting complaint. Is the young, growing animal within breed standards for size and weight? (See Chapter 9.) The condition of the hair coat and presence of external parasites can be noted during the physical examination (e.g., frank hair loss, as seen in louse infestation, or dander and scruffiness of the hair coat, as seen in chronic debilitating diseases). Observe the animal for signs of abdominal splinting or arching of the back, as can be seen with peritonitis. This posture can also be noted with other disease processes when these produce pain in the ventral abdomen. Lateral curvature of the spine could indicate a congenital defect or a chronic spinal lesion. Carrying the tail up away from the body is seen with conditions resulting in pain or irritation in the perineal region, vagina, or rectum. Standing with all four legs in the classic “saw-horse” stance with the neck and tail held erect is typical of tetanus. Abduction of the elbows is seen in disorders that cause thoracic pain. Lameness can be noted by observing unwillingness to bear weight fully on the affected limb, while either standing or walking. Loss of extensor or flexor capabilities of the joints is seen in nerve paralysis or paresis; it can also be caused by tendon and/or joint contractures, in which case joints are rigid. Walking as if all four feet are sore may indicate laminitis. With bright and alert recumbent animals, a thorough examination to rule out fractures or severe joint trauma is essential. Once these have been ruled out, inability to stand may be indicative of generalized muscular paresis or paralysis. These can be of a primary nature, as with lesions within the spinal column causing cord compression, or secondary to mineral or electrolyte deficiencies (e.g., hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia). To be able to judge the behavior of the animal as being normal or abnormal, the observer must call on a large amount of experience. Observing the animal from a distance allows assessment of eating and drinking behavior, as well as assessment of the subject as it is ruminating, urinating, and defecating. How the animal gets up or lies down and how it ambulates are important. Signs indicative of estrus or signs commonly seen with calving might be considered normal or abnormal, given the history and behavior of the animal during these events. Observing the patient during the milking process may also be beneficial. The influence of the manager on animal behavior is important, as is the overall temperament of the particular breed or herd in question. Normal animals react to the approach of a human being by moving away; however, those that have had extensive contact with people may be more inquisitive. Within a herd one can note animals that are more tolerant than others, more stubborn, more restless, and more anxious. These traits are not necessarily abnormal and need to be differentiated from behavior that would be considered secondary to disease. In general, one must determine whether the behavior is one of a depressed or apathetic animal or of a hyperexcitable or frenzied animal. Nutritional status and physical condition are assessed by means of observation and palpation. Special attention is paid to the dewlap, the spinous processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, the shoulder area, and the area around the tailhead. Determination of body condition will then result in a classification of the animal as being anywhere from severely emaciated or cachectic to extremely overconditioned or fat (see Chapter 9 for body scores). Next it must be determined whether the condition is of a primary or nutritional nature or the result of disease. Disease processes can influence or be influenced by the animal’s body condition. Extremely thin animals are seen in primary undernutrition and also with chronic disease. Females carrying multiple fetuses and lactating animals with metabolic abnormalities secondary to abomasal displacements would also show signs of weight loss. Overconditioned animals are at greater risk for a wide variety of disorders primarily related to the accumulation of fat in the liver and excessive fat storage in the omentum. With the animal properly restrained, the physical examination can now progress to specific palpation, auscultation, and percussion. Obtaining a sample of urine for urinalysis is of great value if incorporated into the physical examination; it is easy to perform with the use of dipsticks such as N-Multistix (Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany). Stroking the perineal region can aid in eliciting urination in the female bovine; however, even this is futile if the animal is apprehensive. Consequently, it is recommended that this be done first, while the patient is still fairly relaxed. In the male, elicitation of urination is slightly more difficult and requires massaging of the preputial orifice. Another method is to wash the outside of the prepuce with warm water, but this is less successful. In the female sheep and goat, stroking the perineal area can be attempted, but positive results are rarely achieved. A method that has been reported but which causes the animal great stress is to prevent it from breathing until urination is stimulated. In male or castrated male sheep and goats, gentle massage of the prepuce sometimes results in urination. If that fails, the breath-holding technique can be used. Because of the extreme stress associated with this induced hypoxic state, the author cautions against using this technique and further recommends that it not be attempted on patients that are severely compromised because of any disease process. (See Chapter 22 for further information on interpretation of the urinalysis.) Body temperature is then measured with a rectal thermometer. Normal values for each species are given in Table 1-1. There are no absolute values, and the upper and lower limits should be adjusted as needed to account for ambient temperature and housing. For example, if the ambient temperature is greater than 37.5° C (100° F), a body temperature of 39.5° C (103° F) may still be considered normal for the adult bovine, especially if the animal is not allowed access to shade. When body temperatures approach 41° C (106° F), as a result of high ambient temperatures, heat stroke may occur. Keep in mind that the animal tries to maintain its body temperature within these normal limits, and marked deviation from the norm would be indicative of a disease process. A markedly elevated temperature is seen in acute, severe inflammatory processes. Pathologic lowering of the body temperature is seen in disorders that cause an inhibition of metabolism such as postparturient paresis, neonatal hypoglycemia, the end stages of a chronic disease, or severe septicemia resulting from gram-negative bacteria. There is a normal diurnal variation in body temperature of as much as 0.5° to 1° C (1° to 2° F). In the female there can also be a slight increase in temperature in the days preceding estrus. Neonates are poor thermoregulators and often have a normal body temperature that is 0.5° to 1° C higher than that of adults. TABLE 1-1 Normal Values for Temperature in the Ruminant1–3 In the evaluation of the thoracic and abdominal cavities, the initial step is the ballottement of the abdomen on the right side. An increase in fluid being sequestered intraabdominally could be related to some degree of intestinal or ruminal stasis or associated with an increase in peritoneal fluid, as with peritonitis or ruptured bladder. Ballottement can also reveal whether any firm mass such as a fetus, impacted abomasum, abscess, or tumor is located in the abdomen. In goats the abdominal fat pad is quite prominent and tends to obscure any significant finding on ballottement. Deep palpation of the paralumbar fossa can sometimes reveal masses in this region including lymphomas, fat necrosis, or abscesses. In goats, lambs, and calves, two hands are used to deeply palpate the abdomen; the normal freely movable left kidney is usually readily palpable. On the right side an enlarged or painful liver or kidney can be noted. Palpation of an abnormal swelling or firmness, especially with the elicitation of pain, indicates a problem that must be further evaluated. The spinal column and ribcage are then palpated; the presence of fractures, enlargement of the costochondral junctions, or the elicitation of pain is noted. Enlargement or fractures of the costochondral junctions are commonly seen in young animals with deficiencies of calcium, copper, or vitamin D. Auscultation with concurrent percussion by snapping the finger against the thoracic and abdominal walls is the next procedure. Gas trapped within abdominal viscera elicits a “pinging” sound that can be heard with the stethoscope. Localization of these gas pings to certain areas within the abdomen is helpful in determining which alimentary structure is involved (Figs. 1-3 to 1-5). If the cecum is enlarged and gas filled, an abdominal ping can be heard. This can extend caudally to the tuber coxae and cranially through the paralumbar fossa and under the ribcage on the right side (see Fig. 1-3). The diameter of this area can be variable and range from 6 inches (15 cm) in a cecal displacement to 3 feet (1 m) horizontally in cecal torsions. Spiral colon pings are generally localized to the right dorsocranial paralumbar fossa and rarely extend farther forward than the tenth intercostal space. They tend to be round areas 10 inches (25 cm) or less in diameter centered high under the last rib (see Fig. 1-3) and are commonly found in sick cattle that are anorectic. These pings have no specific diagnostic significance. Gas pings associated with a right-sided displacement or torsion of the abomasum can extend as far cranially as the ninth intercostal space and caudally into the paralumbar fossa (see Fig. 1-4). The diameter of displacements is usually 18 inches (45 cm), whereas that of torsions can be up to 3 feet (1 m). In cases of abomasal volvulus, the animal is usually exhibiting other systemic signs such as increased heart rate, dehydration, depression, scleral injection, and mild colic. In simple right-sided displacements or dilations of the abomasum, the only significant finding may be the small gas ping localized to the abomasum in a cow with depressed appetite and decreased milk production. On the left side, gas pings can be noted as originating from the rumen, the peritoneum, or a left displaced abomasum (LDA). The auscultation of a gas ping that is primarily localized to the dorsal aspect of the paralumbar fossa and auscultable on both sides of the spinal column would be indicative of a pneumoperitoneum. The extent of these pings can be from the thoracolumbar junction caudally to the retroperitoneal space. Pings associated with ruminal tympany occupy the whole of the paralumbar fossa and can extend dorsally to the spinal column but generally do not extend over to the right side (see Fig. 1-5). LDA results in a gas ping that is localized, easily outlined, and approximately 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 cm) in diameter. Caudal extent of the displacement is generally the thirteenth rib; however, it can extend into the paralumbar fossa, in which case the outline of the abomasum can be easily palpated. The LDA should ping over the eleventh rib on a line from the hip to the elbow (see Fig. 1-5). Rumen gas associated with a left-sided ping will rarely ping at this location. Identification of a fluid line within the displacement can aid in diagnosis and is accomplished by balloting the left paralumbar fossa while auscultating the area of the gas ping concurrently, a process known as succussion. LDA often gives a pitch that changes in tone as it is percussed, as a result of movement of the rumen behind the abomasum. Often with LDA, intermittent gas bubbling or “sloshing fluid” sounds are heard. Rumen gas can be further differentiated from gas trapped in an LDA by rectal palpation of the rumen. One can also differentiate rumen gas from that trapped in an LDA by passage of a stomach tube into the rumen. Blowing into the rumen yields obviously auscultable sounds unless an LDA is present, in which case the sounds are muffled as the practitioner listens over the area of the ping. Performing a rumen or abomasal tap, the Liptac test, can further differentiate whether the ping originates from an LDA or the rumen. Fluid collected from an LDA would have a pH of less than 4, whereas that of the rumen should be 6 or higher. The rumen is examined by both auscultation and palpation. It should have a doughy texture with a small gas cap in its dorsal regions and usually is not distended above a plane formed by the coxofemoral joints. Increased accumulation of gas within the rumen would be seen with acute primary frothy bloat and also with free gas bloat. The rumen contractions should be counted, observed, and auscultated. Normally, primary ruminal contractions occur one and one-half to three times per minute, and the force of the contraction should displace the lateral body wall at least The cardiac region of the thorax is auscultated next. Heart rate and rhythm are determined at this time. Rate varies among species, and age differences within species are noted. In general, older or larger animals have a slower heart rate. Table 1-2 lists the ranges of heart rate that are considered normal for the ruminant species, depending on age. Tachycardia can be seen in animals that have been stressed or excited, as in the process of restraint. However, with time the rate should return to within a more normal range. Any deviation from the normal heart rate in a quiet, relaxed animal implies a general disturbance of the normal health of the animal. Increased heart rate can be seen with fever, inflammation, pain, hypocalcemia, or metabolic disturbances that result in hypovolemia. Bradycardia is seen with conduction disorders within the heart muscle and with some metabolic disorders (uremia, hypokalemia). The most common causes of arrhythmias are atrial fibrillation in adult cattle and hyperkalemia in diarrhetic neonates. Location and intensity of the heart sounds are also important to note because muffling or displacement of the sounds can indicate space-occupying lesions within the thorax, pericardium, or mediastinum. With pericardial effusion the heart sounds are initially dull but develop splashy washing machine sounds as a gas-fluid interface develops. This often takes weeks. Normally the heart occupies a space on the ventral thorax between the third and sixth ribs. Most of the heart mass is located on the left side of the chest; thus the heart sounds should be louder on that side. However, if the heart is muffled on the left side and louder than normal on the right, one should consider the possibility of inflammation of the pericardium or lung lobes on the left side of the chest. Displacements of the heart sounds caudally are an indication of a space-occupying lesion in the anterior thorax or mediastinum, such as an abscess or neoplasm. Cranial displacements of the heart sounds would be noted with distention of the ruminoreticulum, eventration of abdominal viscera into the thorax through a diaphragmatic hernia, or other space-occupying lesions as noted previously. If any murmurs are noted on auscultation, an attempt should be made to localize the murmur to a specific heart valve. While the heart is auscultated, the pulse should also be palpated. The easiest point to find a pulse while the heart is being auscultated is at the vascular notch of the mandible where the facial artery is easily palpated. Pulse deficits in conjunction with an increase in heart rate are seen in atrial fibrillation and premature ventricular contractions. The heart rhythm is also noted. Dropped beats, gallop rhythm, and sinus arrhythmias should be compared with other clinical signs to determine importance. TABLE 1-2 Normal Resting Heart Rates (Beats/Min) for Adult and Young (<30 Days of Age) Ruminants1–3

Ruminant History, Physical Examination, Welfare Assessment, and Records

Obtaining the History

Examination

Visual Examination

Physical Examination

Animal

Degrees Celsius

Degrees Fahrenheit

Cattle

Adult

38-39

100.5-102.5

Calf

39-40.5

101.5-103

Sheep

Adult

39-40

102-103.5

Lamb

39.5-40.5

102.5-104

Goat

Adult

38.5-39.5

101.5-103.5

Kid

39-40.5

102-104

to 1 inch (1 to 2 cm). When auscultated, the ruminal contraction sounds like a dull roar that starts quietly, rises to a peak, and dies away. Hypocalcemia and peritonitis are examples of disorders that result in weak or absent ruminal contractions. Hypermotility is rarely seen but can occur and has been described in association with vagal indigestion.

to 1 inch (1 to 2 cm). When auscultated, the ruminal contraction sounds like a dull roar that starts quietly, rises to a peak, and dies away. Hypocalcemia and peritonitis are examples of disorders that result in weak or absent ruminal contractions. Hypermotility is rarely seen but can occur and has been described in association with vagal indigestion.

Animal

Average

Range

Cattle

Adult

60

40-80

Calf

120

100-140

Sheep

Adult

75

60-120

Lamb

140

120-160

Goat

Adult

85

70-110

Kid

140

120-160 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ruminant History, Physical Examination, Welfare Assessment, and Records

Chapter 1