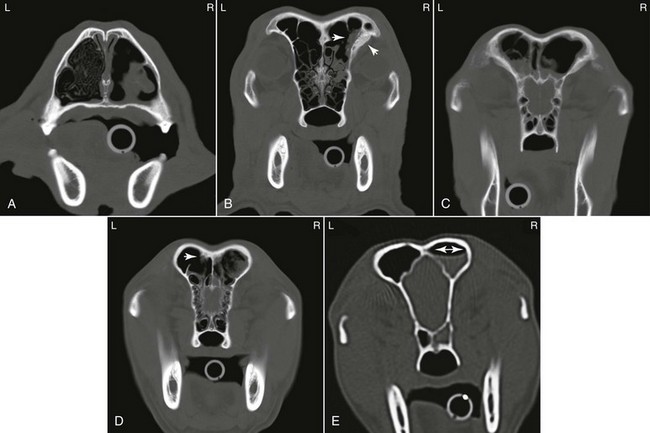

Chapter 154 The causes of nasal discharge and obstructive nasal breathing in the dog are listed in Box 154-1. The principal diseases associated with chronic rhinitis are sinonasal neoplasia, idiopathic lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis, and fungal rhinitis (Lefebvre et al, 2005). Nasal discharge is not limited to primary nasal disease but also may occur with systemic and extranasal disorders. Extranasal disorders often have systemic signs (e.g., depression, pyrexia, hemorrhage) and a history of acute onset, whereas primary nasal disorders have a more chronic nature. Important extranasal disorders that may manifest with nasal discharge include coagulopathies, vasculitis, hypertension, hyperviscosity syndrome, and pneumonia. Clinical history and physical examination findings generally offer an indication of primary nasal disease as opposed to systemic or extranasal disease. Routine laboratory tests (complete blood count, serum chemistry panels, urinalysis), coagulation profile, blood pressure, and thoracic radiographs are important to rule out most of the systemic or extranasal causes of nasal discharge. Cytologic evaluation of nasal discharge is rarely helpful except possibly for identification of Eucoleus (Capillaria) boehmi parasitic ova. Performing bacterial and fungal cultures of nasal discharge is not recommended because results are nonspecific and simply represent resident bacteria and fungi. Serologic testing for aspergillosis should be considered, because a positive result is highly suggestive of disease, although a negative result does not rule out nasal infection (Pomrantz et al, 2007). Empiric antimicrobial treatment is not advised and merely delays definitive diagnosis unless chronic Bordetella bronchiseptica or Pasteurella multocida rhinitis (both very rare) or pneumonia is present. Diagnostic imaging studies are performed with the patient under anesthesia. Imaging studies often are essential in dogs with chronic rhinitis to help reach a diagnosis. It is critical that imaging studies be completed before rhinoscopy or collection of intranasal samples so that blood from secondary hemorrhage does not obscure subtle lesions or affect the quality of diagnostic images. If dental disease is suspected, dental radiographs are recommended to evaluate teeth and surrounding structures. Radiographic images of the nose and sinuses may provide some insight but often do not reveal a specific cause of the nasal disease. Radiographs often lack sufficient resolution to identify or localize early nasal disease. Computed tomography (CT) is vastly superior to plain radiography of the nasal cavity (Lefebvre et al, 2005). Nasal CT provides a thorough assessment of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses and provides superior insight into the nature and extent of disease. Contrast-enhanced CT images are useful to distinguish between vascularized soft tissue and mucus accumulation. Because nasal CT clearly demonstrates the location and extent of nasal disease, it is often used to help guide postimaging rhinoscopic and biopsy procedures and delineate nasal tumors for radiation therapy. If routine diagnostic steps do not provide a cause for rhinitis, referral to an institution providing CT imaging is advised. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often considered superior to CT for delineation of tumor borders, a recent study failed to document an advantage of MRI over CT in detecting intracalvarial changes in dogs with nasal neoplasia (Dhaliwal et al, 2004). Tissue samples are not submitted routinely for bacterial or fungal culture except when fungal plaques are detected (Pomrantz et al, 2007) or sometimes when a foreign body is identified. To confirm a diagnosis of aspergillosis, a positive result on fungal culture should be supported by diagnostic imaging, cytologic, rhinoscopic, or histologic evidence of infection. Primary bacterial rhinitis is exceedingly rare in the dog, and almost all bacterial infections develop secondary to underlying primary nasal disease. A heavy growth of even one or two bacterial isolates may merely be indicative of bacterial colonization; however, pure isolates of B. bronchiseptica and possibly of P. multocida may be significant if the clinical history is supportive. If tissue cultures are performed, the results must be interpreted carefully in light of histopathologic and other diagnostic information. Geographic locality plays a role but, excluding nasal foreign bodies (Aronson, 2004) and dental disease, the most common causes of chronic rhinitis in dogs are neoplasia, idiopathic chronic (lymphoplasmacytic) rhinitis, and fungal rhinitis. Parasitic rhinitis is uncommon. The treatment for nasal mites (Pneumonyssus caninum) is ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg PO, with the dose repeated in 2 to 3 weeks. Selamectin has been reported effective at 6 to 24 mg/kg for three doses at 2-week intervals, and milbemycin is recommended for use in dogs with possible MDR-1 (multidrug resistance protein 1) mutations using a dosage of 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg body weight PO once a week for 3 weeks. The treatment for nasal nematodes (E. [Capillaria] boehmi) is not clearly defined, although ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg PO once or fenbendazole for 2 weeks reportedly have been effective. Allergic rhinitis often is mild, but if it is severe, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, or trimeprazine/prednisone (Temaril-P) may be prescribed to control clinical signs. In the rare situation of bacterial rhinitis caused by B. bronchiseptica, doxycycline 5 to 10 mg/kg every 12 hours PO for 2 weeks may be effective. Nasal aspergillosis is most commonly seen in young to middle-aged dolichocephalic dogs, although older-aged dogs should not be excluded. Sinonasal aspergillosis is a noninvasive disease in dogs with fungal hyphae confined to the surface of the mucosa and not within or below the surface mucosa. The bony destruction seen with this disease is not caused by the fungus itself but appears to result from the host inflammatory response due to an aberrant dysregulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Systemic immunosuppression is not present in affected dogs. Local immune-dysfunction owing to imbalance between proinflammatory and antiinflammatory signals is likely involved in the pathogenesis of this disease. Dysregulation of genes encoding Toll- and Nod-like pattern recognition receptors involved in the innate immune response in the nasal mucosa of dogs with sinonasal fungal rhinitis has recently been described (Mercier et al, 2012). Affected dogs often have copious unilateral or bilateral mucopurulent nasal discharge. The volume of nasal discharge is often less in dogs with primary fungal frontal sinusitis. Sneezing is common and may be accompanied by mild to severe epistaxis. Facial pain and depigmentation and ulceration of the nasal planum may be present. Unlike in nasal neoplasia, facial distortion is unusual in all but advanced cases of fungal rhinitis. Nasal CT images (Figure 154-1) along with rhinoscopy findings are noteworthy for the presence of dramatic turbinate loss within the nasal cavity (Saunders et al, 2004). Frontal sinus involvement may be present and is characterized on CT by an irregularly marginated soft tissue attenuating density within the affected sinus (see Figure 154-1). Mucosal thickening and bone remodeling of the affected sinus may also be seen. Invasion through the maxillary or palatine bones with extension into surrounding soft tissue structures is seen occasionally. Nasal CT is preferred over radiography so that the integrity of the cribriform plate can be evaluated before local antifungal therapy is initiated. Diagnosis of nasal aspergillosis is confirmed by visualization of fungal plaques on nasal or sinus mucosa and demonstration of branching septate hyphae on cytologic or histologic examination of samples from affected regions within the nose. Serologic tests positive for aspergillosis also support the diagnosis, although negative results may occur even with extensive disease. Occasionally special staining methods for fungi may be useful for identifying fungal elements in tissue biopsy samples. Repeated sampling or a trial of antifungal drugs may well be indicated in dogs for which the index of suspicion for nasal aspergillosis is high; however, extensive débridement of fungal plaques should be performed before treatment. Figure 154-1 A, Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the middle region of the nasal cavity in a dog with nasal aspergillosis involving the right nasal cavity and right frontal sinus. The right nasal cavity is largely devoid of turbinate structures with scattered regions of soft tissue attenuating densities (mucopus) present. The left nasal cavity has normal turbinate structures present. B, CT scan for the same patient at the level of the rostral frontal sinuses. There is a fungal plaque in the right ventrolateral frontal sinus (arrow in sinus) characterized by an irregularly marginated amorphous soft tissue attenuating density along the frontal bone. Adjacent to the fungal plaque, periostitis of the ventrolateral aspect of the right frontal bone is present. C, CT scan in another patient at the level of the midregion of the frontal sinuses with bilateral fungal sinusitis. Within both sinuses the fungal plaques are seen irregularly marginated amorphous soft tissue attenuating material. Mucosal thickening of the frontal sinuses bilaterally is present. Mild periostitis of the ventrolateral aspect of the left frontal bone is present. D, CT scan in another patient with fungal sinusitis. A large irregularly shaped heterogenous representing a fungal plaque is present in the right frontal sinus. Mucosal thickening of the right frontal sinus is present. A small fungal plaque is present in the dorsal aspect of the left frontal sinus (arrow). The structure is irregularly marginated and associated with mild periostitis adjacent to the fungal plaque. E, CT scan showing a meniscus in the right frontal sinus, which is consistent with fluid caused by obstruction rather than the irregularly marginated amorphous soft tissue attenuating densities seen with fungal sinusitis.

Rhinitis in Dogs

Diagnosis

Treatment of Common Causes of Rhinitis

Fungal Rhinosinusitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rhinitis in Dogs

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue