13 Reproductive Disorders

General Diagnostic Approach

For all males, history should investigate changes in the appearance of external genitalia, preputial discharge, excessive licking of genitalia, and changes in urinary patterns. For breeding males, history should include libido, mating ability, number of females bred, conception rate, breeding methods (i.e., natural or artificial insemination, frequency of use, how insemination dates are chosen), and reproductive performance of bitches before and after being bred to the male in question. Reproductive history should include methods used to screen for infectious diseases affecting reproduction (e.g., Brucella canis in dogs and viral rhinotracheitis in cats) (see Chapter 15), medications known to affect reproductive function (e.g., glucocorticoids), familial association with infertility, and stressful activities such as racing or being shown.

Vaginal Cytology

Hemorrhage

RBCs are common in normal and abnormal vulvar discharges (Box 13-1); their significance is determined by accompanying cells. Superficial (cornified) vaginal epithelial cells with RBCs are expected during normal proestrus and estrus but may also occur because of exogenous estrogens or ovarian pathology such as follicular cysts or ovarian remnants. RBCs mixed with mucus are found in lochia, the normal postpartum vaginal discharge. When cytology reveals peripheral blood with occasional intermediate and parabasal epithelial cells, causes of hemorrhage should be sought. These include subinvolution of placental sites, vaginal laceration, uterine and vaginal neoplasia, uterine torsion, and coagulopathies.

Box 13-1 Causes of HEmorrhagic Vulvar Discharge in the Bitch and Queen

With Mainly Superficial (Mature) Epithelial Cells (estrogen influence)

Normal estrus; or late proestrus or early diestrus (most common)

Ovarian pathologic condition (i.e., cystic follicles, functional ovarian tumor)

Leiomyoma is the most common uterine and vaginal tumor in small animals, and hemorrhagic vulvar discharge, with or without a palpable mass, is the most common sign. Leiomyomas do not readily exfoliate; therefore neoplastic cells are rarely found cytologically. Uterine torsion occurs almost exclusively in periparturient females. Abdominal pain and unrelenting straining are the prominent findings, and a hemorrhagic discharge is common. Abdominal ultrasound is indicated. Vulvar bleeding is rarely the only clinical sign of a coagulopathy. If a bleeding disorder is suspected, a hemostatic profile (see Chapter 5) is indicated.

Purulent or Septic Discharge

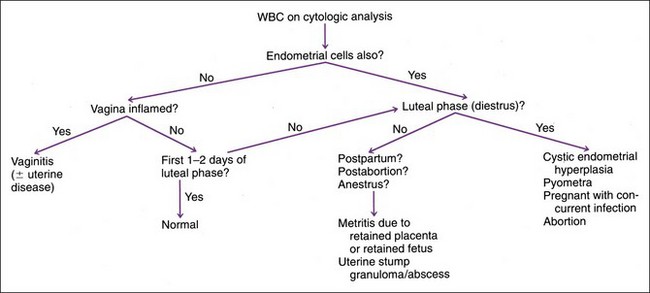

Bleeding can accompany any inflammatory process. If the WBC : RBC ratio is more suggestive of an exudate than of peripheral blood, an inflammatory disease should be sought. WBCs suggest inflammation, but they are normally found in large numbers during the first 1 to 2 days of diestrus and in lesser numbers in normal lochia. Septic (i.e., bacteria seen) or purulent vulvar discharges may originate from vulva, vestibule, vagina, or uterus. The source of a septic/purulent exudate determines prognosis and must be identified. Vaginoscopy is a reasonable next step. Hyperemia, edema, or mucosal lesions should be obvious with vestibulitis or vaginitis. These would not exclude concurrent uterine pathology (Figure 13-1). If endoscopy suggests a uterine and/or cervical source of discharge or if endometrial cells are found during cytologic evaluation, uterine involvement is probable and abdominal ultrasonography is indicated.

FIGURE 13-1 Diagnostic considerations for purulent or septic vaginal cytology. WBC, White blood cells.

Mucus

This is the predominate component of lochia. Mucoid discharge may also occur during normal late pregnancy and possibly in scant amounts during the nonpregnant, luteal phase (i.e., diestrus). Further testing of these otherwise healthy animals is usually unnecessary. Cervicitis, mucometra, and androgens can also cause mucoid discharge. Conversely, a scanty mucoid vulvar discharge is apparently normal in some otherwise healthy bitches (Box 13-2).

Vaginal Epithelial Cells

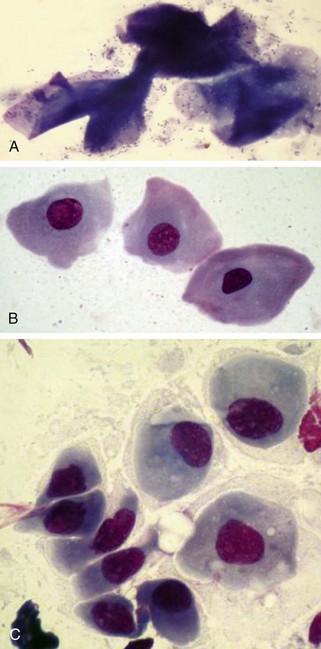

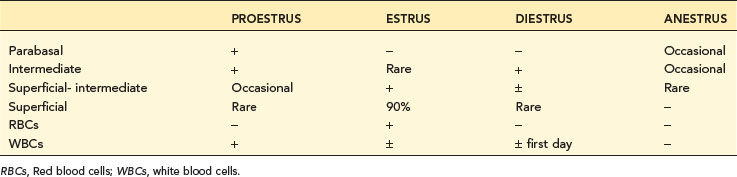

Estrogen causes proliferation and cornification of vaginal epithelium. Therefore vaginal cytology can be used to monitor estrous cycle, especially the follicular phase of proestrus and estrus when ovarian follicles are producing estrogen (Figure 13-2). During proestrus, parabasal, intermediate, and some superficial cells are exfoliated. RBCs, WBCs, and bacteria are present. As estrogen increases, there is a gradual increase in numbers of cornified epithelial cells and a decrease in WBCs. During estrus, superficial (cornified) cells predominate, eventually accounting for greater than 90% of the exfoliated epithelial cells. RBCs and extracellular bacteria are often present (Table 13-1). WBCs are absent during estrus unless concurrent inflammation exists.

Diestrus (luteal phase) is marked by an abrupt change: parabasal and intermediate cells outnumber the superficial cells. Sheets of epithelial cells are often noted at the onset of diestrus. WBCs almost always return at this time. RBCs and bacteria are often present. Thus it is often impossible to base differentiation of late proestrus from early diestrus on a single vaginal smear. Fewer cells are exfoliated during anestrus; therefore the preparations are relatively acellular. Parabasal and intermediate epithelial cells, with or without a few WBCs and bacteria, are present during anestrus (see Table 13-1). Similar changes occur during the feline estrous cycle, except that RBCs and WBCs are uncommon.

Canine Breeding and Whelping Management

Determining stages of the estrous cycle helps determine optimal breeding dates to maximize conception and litter size and to predict whelping dates more accurately. When using vaginal cytology as the only laboratory aid to breeding management, maximal conception rates and litter size are obtained when normal bitches are bred on the first day of estrus and again 3 or more days later. Although it may not change conception rates or litter size, breeding every other day is also acceptable (Box 13-3). Normal gestation length varies from 58 to 72 days after the first breeding date. When gestation length is calculated from the first day of cytologic diestrus, 93% of bitches whelp 57 days after day one of diestrus. Calculating gestation length from cytologic diestrus instead of breeding dates is helpful for recognizing prolonged gestation or premature delivery.