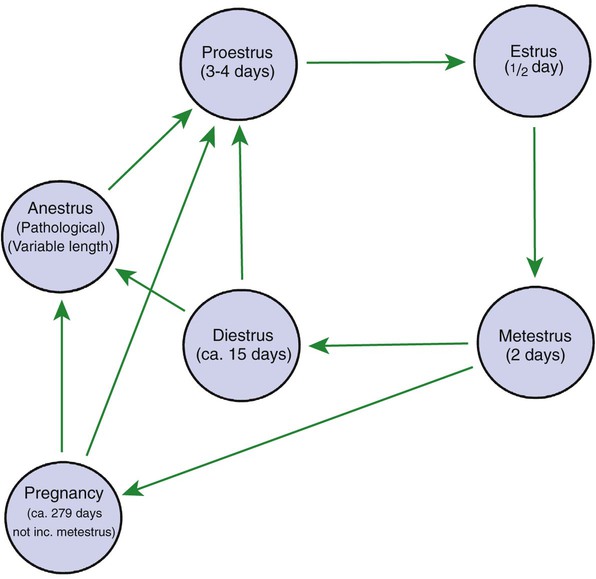

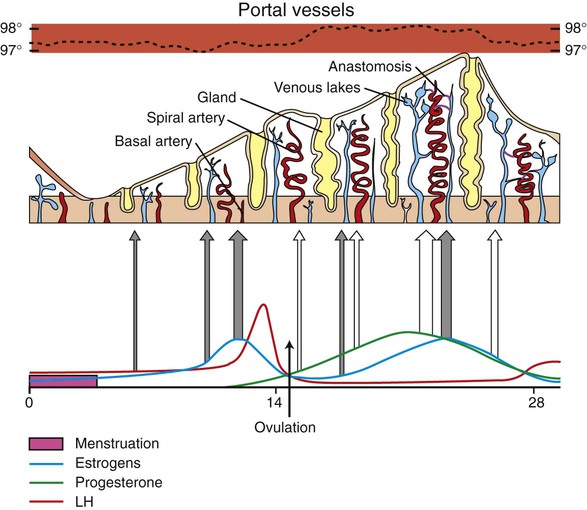

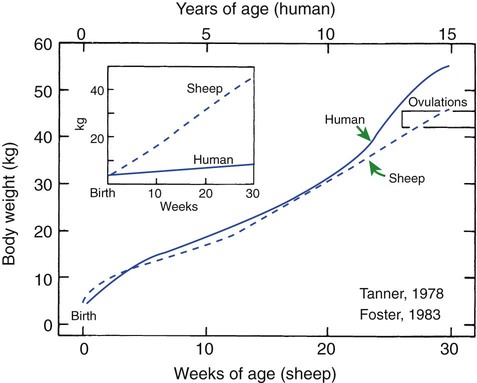

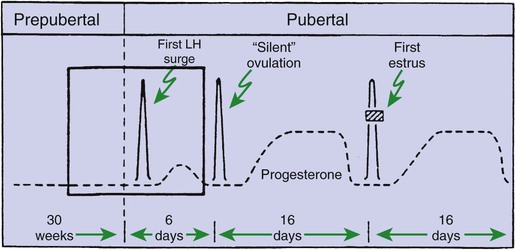

1. The two types of reproductive cycles are estrual and menstrual. Puberty and reproductive senescence 1. Puberty is the time when animals initially release mature germ cells. 2. Reproductive senescence in primates occurs because of ovarian inadequacy, not inadequacy of gonadotropin secretion. 1. Sexual receptivity is keyed by the interaction of the hormones estrogen and progesterone, via gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the female and testosterone in the male. External factors controlling reproductive cycles 1. Photoperiod, lactation, nutrition, and animal interaction are important factors that affect reproduction. 2. Inadequate nutrition results in ovarian inactivity, especially in cattle. Domestic animals have limited periods of estrus (or sexual receptivity); the term estrous cycle is used, and the onset of proestrus defines the start of the cycle (Figure 37-1). Primates are sexually receptive during most of the reproductive cycle; the term menstrual cycle is used, with the onset of menstruation (vaginal discharge of blood-tinged fluids and tissues) designated as the start of the cycle (Figure 37-2). The first day of the cycle for both estrual and menstrual cycles in many species begins shortly after the end of the luteal phase. In the dog a normal anestrous period separates diestrus and proestrus (the stages of the cycle are described later). The estrous cycle has been classically divided into stages that represent either behavioral or gonadal events (see Figure 37-1). The terminology, originally developed for the guinea pig, rat, and mouse, is as follows: • Proestrus. Period of follicle development, occurring subsequent to luteal regression and ending at estrus. • Estrus. Period of sexual receptivity. • Metestrus. Period of initial development of the corpus luteum (CL). For females to begin reproductive cycles, they must undergo a process called puberty. The term puberty is used to define the onset of reproductive life. For the female, although the onset of sexual activity (in domestic animals) or first menstrual bleeding (in primates) is often used as the onset of puberty, the most precise definition is the time of first ovulation. For all species, there is a critical requirement for the attainment of a certain size in order for puberty to be initiated, in cattle about 275 kg, for example, and in sheep about 40 kg (Figure 37-3). If this critical requirement is not met because of inadequate nutrition, puberty is delayed. The age at puberty for domestic animals is as follows: cats, 6 to 12 months; cows, 8 to 12 months; dogs, 6 to 12 months; goats, 7 to 8 months; horses, 12 to 18 months; and sheep, 7 to 8 months. Classically, bitches have attained 75% of their adult size before puberty occurs. With appropriate growth and photoperiod exposure, the secretion of gonadotropins in lambs causes significant follicle growth. This growth is maintained because of decreased sensitivity of the hypothalamus to estrogens produced by growing follicles. The first endocrine event of puberty in the ewe lamb is the appearance of a preovulatory-type surge of gonadotropins, presumably induced by estrogens produced by developing follicles (Figure 37-4). The gonadotropin surge results in the production of a luteal structure, through luteinization of a follicle(s), which has a short life span, 3 to 4 days. After the demise of the initial luteal structure, another gonadotropin surge occurs, leading to ovulation and the formation of a CL, usually of a normal life span. At this time, cyclical ovarian activity is finally initiated in the ewe lamb.

Reproductive Cycles

Reproductive Cycles

The Two Types of Reproductive Cycles Are Estrual and Menstrual

Puberty and Reproductive Senescence

Puberty Is the Time When Animals Initially Release Mature Germ Cells

Reproductive Senescence in Primates Occurs Because of Ovarian Inadequacy, Not Inadequacy of Gonadotropin Secretion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree