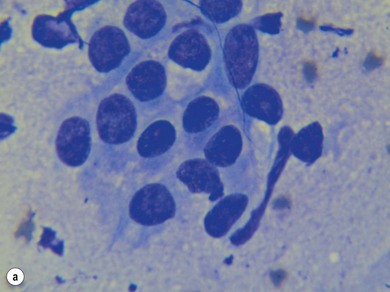

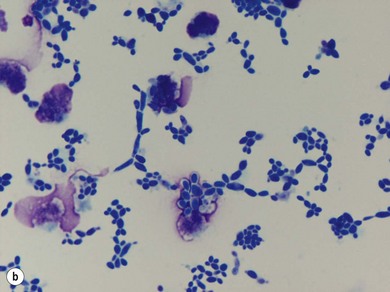

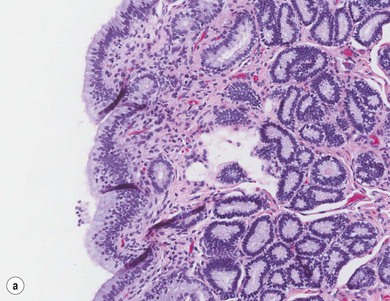

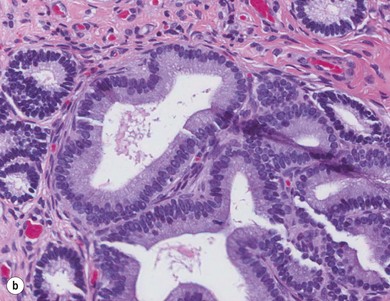

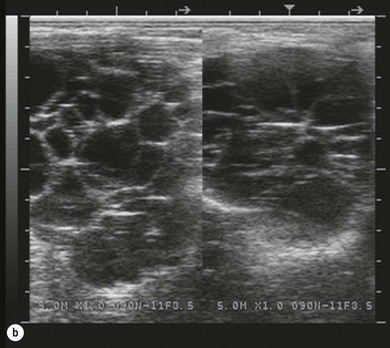

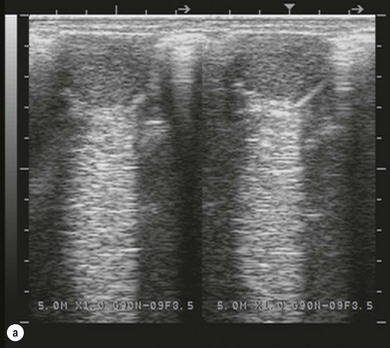

Chapter 14 • Usually lasts 5–7 days; oestrus behaviour typically ceases 24–48 hours after ovulation. • Mare is sexually receptive – stands to be mounted, seeks stallion’s attention, squats, raises the tail, rhythmically everts the clitoris (‘winking’) and urinates, does not flatten ears or kick (Figure 14.1). • The cervix becomes increasingly pink, moist, relaxed, open and oedematous. When it is fully relaxed, the caudal portion of the cervix lies on the floor of the vagina. • The uterus is oedematous and flaccid. On ultrasonographic examination, the oedematous endometrial folds make the cross-section of the uterine horn resemble a sliced tomato or a wagon wheel (Figure 14.2). Endometrial oedema declines as the follicle matures and approaches ovulation and it is typically minimal at ovulation. • Characterized by high concentrations of oestrogen and luteinizing hormone (LH) and basal concentrations of progesterone. Follicles often soften 24 hours prior to ovulation, but some become turgid again prior to ovulation. The mare is frequently sensitive to the palpation of the ovary at this time due to the relatively large diameter of the preovulatory follicle and its proximity to the broad ligament. The preovulatory follicle increases from approximately 30 mm 6 days prior to ovulation to an average of 45 mm by the day of ovulation. At the height of the breeding season, however, it is not unusual for a mare to be in oestrus for only 3–4 days and ovulate a follicle of less than 35 mm in diameter. On ultrasonographic examination the pre-ovulatory follicle becomes less circular and tends to ‘point’ towards the ovarian fossa – the ultimate site of rupture for follicles in the mare. • Following ovulation, the follicular cavity fills with blood and is termed a corpus haemorrhagicum (CH). Double ovulations occur in approximately 16% of cycles with the highest incidence in Thoroughbreds, Warmbloods and draught horses. The average interval between ovulations is 1 day with a range of 0–5 days. • Mare actively rejects the stallion – clamps tail down, swishes tail, flattens ears, strikes, squeals, bites. • A corpus luteum (CL) is present on the ovaries. The CL may be fluid-filled (50%) or non-fluid-filled (Figure 14.3). The CL is not normally palpable in the mare. • The cervix is pale, firm, dry and closed. The caudal portion of the cervix is positioned high in the vaginal lumen, lifted by the dorsal cervical ligament. • Uterine tone increases, and the uterine horns become tubular. • Characterized by high circulating concentrations of progesterone that rise sharply following ovulation. Prostaglandin F-2α, released from the uterus on day 14 or 15, causes luteolysis and return to oestrus. • Mares can have considerable follicular growth during dioestrus. Ovulation occasionally occurs during dioestrus despite the presence of high concentrations of progesterone and absence of oestrous behaviour. • Occurs before and after seasonal anoestrus. • In early spring, oestrous behaviour may be observed intermittently or continuously for several weeks; however these transitional cycles are anovulatory. The first ovulation of the season is generally followed by normal, cyclic activity. • Clusters of large follicles (>30 mm) are often found on the ovaries, but there is no ovulation. • The cervix does not close tightly until the mare ovulates. General physical: Check for the presence of any painful or chronic conditions, especially those related to the musculo-skeletal system. Examination of external genitalia: 1. Vulva: the vulvar lips should meet evenly. For maximal function the dorsal commissure of the vulva should be no more than 4 cm above the pelvic floor; at least 2/3 of the vulva should be positioned below the pelvic floor There should be a cranial-to-caudal slope of no more than 10° from the vertical (Figure 14.4). 2. Discharge on the vulvar lips, tail or hindquarters. 3. Clitoris: can harbour contagious equine metritis (CEM) organism (Taylorella equigenitalis) or other venereally transmissible organisms. Use a standard hospital-type swab to sample the clitoral fossa. A narrow-tipped (paediatric-type) swab is then used for the central and, if present, lateral clitoral sinuses (Figure 14.5). The swabs are then placed in Amies charcoal transport medium and kept at 4°C until their arrival at the laboratory. If more than one mare is being swabbed a disposable glove should be worn on the hand used to evert the clitoris. Examination of internal genital tract: Palpation per rectum and transrectal ultrasonography: 1. Cervix: correlate shape and consistency with cycle stage. 2. Uterus and endometrial folds. Check for: Presence of free fluid in the lumen. Presence of endometrial cysts. Presence of endometrial oedema. Sacculations: commonly at body-horn junction. Pregnancy; embryonic vesicles measuring 5 mm in diameter (~10–11 days of pregnancy) are detectable by most available ultrasound equipment. Endometrial swabbings for microbiological culture: Bandage the mare’s tail or place in plastic sleeve. Wash perineum thoroughly with mild soap or povidone-iodine solution, rinse and dry. Use sterile sleeve or clean sleeve and sterile surgeon’s glove. Lubricate with a small amount of sterile water-soluble lubricant. Use double-guarded swab (Figure 14.6). Try to avoid sampling the uterus during dioestrus because of high susceptibility to infection at this stage of the cycle. If examination of the mare is necessary during dioestrus, administer a luteolytic dose of PGF2α at the end of the procedure. Endometrial cytology: Obtain smear from aspirated uterine fluid or from swab. Cytology brushes are also available and provide better sampling of endometrial cells for the cytology smear. Stain with ‘Diff-Quik’. The presence of neutrophils suggests active endometritis. Fungal elements, if present, are readily observed in the endometrial cytology smear (Figure 14.7) 1. Speculum: the vestibulovaginal seal serves as a barrier to ascending bacterial infection. This seal is best tested during oestrus using a mildly lubricated speculum. If the seal is effective, resistance will be met. The windsucker test can also be performed to evaluate the integrity of the vestibulovaginal seal. When the labia are gently parted, mares with a weak, incompetent vestibulovaginal seal produce a characteristic sound, indicating air inrushing into the vagina (windsucker). If the mare has a competent vestibulovaginal seal, air does not enter the vagina. Appearance of cervix and vagina. Vaginal varicosities in region of vestibulovaginal seal (Figure 14.8). Endometrial biopsy: Use Bouin’s fixative. Endometrial biopsy is used as a prognostic indicator to evaluate ability of a mare to carry a foal to term. Abnormalities seen include: The following diagnostic aids are not carried out routinely during a breeding soundness examination. Ovarian neoplasm: Ovarian tumours are not uncommon in mares. They may cause abdominal pain and discomfort to the mare if they reach a sufficient size. Granulosa-cell tumour: most common ovarian tumour. It originates from the sex cord stromal tissue, is usually multilocular, benign, unilateral and often secretes hormones (Figure 10a). Clinical signs: One ovary is enlarged and has no ovulation fossa. The contralateral ovary is usually small and firm and has no follicular activity because of: • Suppression of gonadotropins by negative feedback from ovarian steroids and persistent elevated concentrations of inhibin produced by the tumour. Behaviour varies depending on the predominant hormone secreted: Diagnosis: Palpation and ultrasonography of an enlarged ovary with a small inactive contralateral ovary. Ultrasonographic findings may range from a uniformly dense structure to a structure containing one or many large cysts (Figure 10b). Haematoma: A haematoma results from the follicular cavity overfilling with blood after ovulation or from an anovulatory follicle that becomes haemorrhagic. It can become quite large (>10 cm), but usually regresses within 2–3 cycles, occasionally leaving a calcified nodule. The mare continues to cycle normally. Occasionally a haematoma may expand to destroy part or all of the ovary (Figure 14.11). On rare occasions, ovarian haematomas fail to organize, get to unusually large sizes and become filled with fibrinosuppurative material (Figure 14.12), leading invariably to adhesions and inflammation of surrounding tissues including the gastrointestinal tract. Unresolved ovarian haematomas that reach sizes greater than 15 cm in diameter should be removed surgically to avoid life-threatening complications. Anovulatory follicles: These may be termed persistent or autumn follicles. They can be 10–15 cm in diameter and are commonly found in autumn associated with declining concentrations of LH. They are nonpathological structures containing blood, which can be gelatinous in consistency. The ultrasonographic appearance of the uterus is that of a uterus in diestrus rather than estrus. 1. Mesonephric origin – cysts located adjacent to the ovary. Usually called paraovarian cysts. 2. Paramesonephric origin – cysts in the region of the ovarian fossa, but are not of ovarian origin. 3. Epithelial inclusion cysts – often called fossa cysts. Originate in the ovarian fossa. Surface epithelium is disrupted at ovulation and becomes pinched off and embedded in the ovarian cortex (Figure 14.13). The cysts can become numerous in old mares and can eventually obstruct ovulation. In severe cases, most of the ovary can be destroyed by pressure necrosis. Endometritis: Persistent mating-induced endometritis is probably the commonest cause of subfertility in mares. Aetiology: Normal, resistant mares are able to clear bacteria from the uterus within 72 hours. Susceptible mares appear to have defects in uterine contractility and/or uterine immune defence mechanisms and remain infected after bacteria are introduced into the uterus. The three physical barriers to microorganisms gaining entrance to the uterus are the vulva, the vestibulovaginal seal and the cervix. If any of these structures are incompetent the mare is predisposed to developing persistent endometritis. Another aggravating factor in the pathogenesis of endometritis is delayed uterine clearance, which refers to the mare’s failure to mechanically clear the uterus of fluid and contaminants associated with mating or artificial insemination. • Correct any predisposing conformational defects. • Remove fluid from the uterus by lavage with sterile, isotonic saline solution. Can use oxytocin (10–20 IU IV) to assist in fluid removal. • Infuse uterus with antibiotic (choice depends on microorganism cultured – use IV preparation). Dilute antibiotic into 30–60 mL for intrauterine infusion. • Treat the mare daily during oestrus (short cycle with PGF2α if necessary). • If the uterus contains a large amount of fluid on the day before breeding, flush with consecutive litres of buffered, isotonic saline solution (non-irritant) until the recovered fluid is clear. Lavage of the uterus with mucolytic agents (acetylcysteine) may be helpful to remove bacteria that form biofilms in the endometrium. Infuse broad-spectrum antibiotic or choose antibiotic based on antimicrobial sensitivity testing. • Use artificial insemination if possible. Otherwise, infuse 100 mL of semen extender containing an appropriate antibiotic into the uterus immediately prior to covering. • Flush the uterus with consecutive litres of buffered, isotonic saline solution not earlier than 4 hours after breeding until the recovered fluid is clear. Infuse antibiotic. • Repeat flushing and infusion of antibiotic until one day after ovulation. Oxytocin can be administered to ensure 100% fluid recovery during these flushes. Aetiology: The entire uterine wall is inflamed. Metritis occurs after parturition and is often related to trauma. It can be secondary to retained placenta. Toxins can pass through the uterine wall to the general circulation. Endometrosis (formerly called chronic degenerative endometritis): Chronic degenerative changes occur within the endometrium, increasing with age. There are three main pathological findings: 1. Periglandular fibrosis – fibrosis around the glands. Associated with reduced ability to carry a foal to term (Figure 14.9b). 2. Cystic glandular distension – dilated glands. Commonly contain inspissated secretion. Fibrosis may interfere with glandular secretion. 3. Endometrial cysts – may interfere with pregnancy if extensive. Caused by coalescence of lymphatic lacunae (enlarged lymphatics). If large, can surgically excise via endoscope using biopsy instrument, electrocautery or laser. Some workers have advocated the use of repeated flushes using hot (45–50°C), hypertonic saline solution to enhance uterine contraction. Diagnosis: Diagnosis is by hysteroscopy. There may be single or multiple bands, partial or complete sheets or tunnels between adjacent endometrial folds. They result in infertility if extensive, cause pyometra or impede movement of embryo, which is necessary to signal maternal recognition. Pyometra: Unlike the cow, pyometra in the mare is not always accompanied by a retained corpus luteum and anoestrus. Affected mares may cycle regularly or may have short cycles due to premature release of PGF2α. The uterus may accumulate 0.5 to 60 L of exudate. Mares with pyometra frequently have a fibrosed or occluded cervix. Usually there are no systemic signs. Uterine abscess: This is rare. It can be secondary to dystocia, AI, severe metritis or uterine therapy. In the acute phase, there may be systemic signs – fever, neutrophilia, peritonitis. If small, can attempt surgical drainage into the uterus; otherwise, use abdominal approach. Poor prognosis for future breeding. Uterine neoplasia: Leiomyomas or sarcomas are rare. Diagnosis: Diagnosis is by palpation and ultrasonography per rectum. Classification of tumour is by histopathological exam after surgical removal. Contagious equine metritis (CEM): Aetiology: This disorder is caused by Taylorella equigenitalis, a microaerophilic, Gram-negative coccobacillus. Transmission is venereal. The organism persists in clitoral sinuses (under anaerobic conditions) of carriers. Stallions are inapparent carriers. In some countries CEM is a reportable disease. Clinical signs: Signs are severe endometritis with profuse watery, mucopurulent discharge. Mares have short oestrous cycles. Chronic infection can develop when clinical signs are not obvious. A symptomless carrier state can also exist. Aetiology: Cervicitis is usually associated with vaginitis and/or endometritis. Apart from infection, it can be associated with irritants, such as air or urine in the vagina, and uterine medications. Diagnosis: Diagnosis is by direct visualization of the caudal aspect of the cervix using speculum examination. Diagnosis: Diagnosis is by digital examination of the cervix while it is under the influence of progesterone (dioestrus). Treatment: Treatment involves surgical correction by a 2- or 3-layer closure after evaluating the endometrium by endometrial biopsy. Mares are given a sedative/analgesic combination of romifidine or xylazine plus butorphanol or epidural anaesthesia plus sedation. Retraction of the cervix may be facilitated by infiltration of local anaesthetic solution dorsal to the cervix. An incision is made along the scar of the healed edges of the tear and extended 1 cm cranial to the end of the tear, to ensure separation of mucous membrane from the fibromuscular layer. The wound can be sutured in three layers (internal mucous membrane, fibromuscular, and external mucous membrane) using a continuous horizontal mattress for the outer and inner layers and a continuous suture for the fibromuscular layer, or two layers (internal mucous membrane + inner fibromuscular layer, outer fibromuscular layer + external mucous membrane) in a continuous suture pattern using absorbable suture. The lumen of the cervix should be checked for patency throughout the procedure. Give a course of antibiotics plus NSAIDs if necessary. Wait 30 days before breeding. Advise the owner that the cervix may tear again at the next parturition. Pneumovagina (windsucking): This is an important and relatively common condition. • Poor vulvar and perineal conformation, especially the presence of an incompetent vestibulovaginal seal (Figure 14.4) (2nd physical barrier to potential contaminants to the uterus). • Poor body condition predisposes. • <2/3 of the vulvar lips below the level of the tuber ischii. Treatment: Treatment is Caslick’s vulvoplasty. Treat endometritis first. Infiltrate vulvar margins with local anaesthetic solution from just below level of the ischium to the dorsal commissure. Remove a 1-cm strip of mucosa from the mucocutaneous margin (N.B. do not remove skin). Use continuous or interrupted sutures to appose denuded tissue surfaces. Remove sutures after 10–12 days. Do not close vulva excessively – predisposes to urovagina. A ‘breeder’s stitch’ of umbilical tape can be placed at the ventral edge of the repair to protect the suture line during coitus until the mare is confirmed pregnant. Alternatively, surgical staples may be also used to provide temporary vulvar closure until the mare is examined for pregnancy, especially for maiden mares. Open vulvoplasty prior to foaling. The vulvoplasty should be closed as soon as possible after foaling unless there is significant oedema or uterine lavage is necessary. Urovagina: Urine accumulates in the vagina (urine pooling, vesicovaginal reflux) causing inflammation. The condition is associated with poor conception and early embryonic death. Treatment: Treatment depends on the cause. Poor body condition should be corrected. Urogvagina may correct itself if it occurs after foaling. In mild cases, mares can conceive if urine is physically removed from the vagina before breeding. Intrauterine infusion of semen extender protects sperm from the deleterious effects of urine. If there is injury to the vestibulovaginal seal or if the vagina has a severe cranioventral slope, surgery is required. Urethral extension appears to give the most reliable results. The mare is sedated, and epidural anaesthesia is induced. After appropriate cleansing of the region, the vulvovaginal fold (urethral fold or transverse fold) is retracted with forceps. The dorsal mucosa and submucosa of the vulvovaginal fold are incised horizontally along the dorsal edge 2–4 cm cranial to its caudal border. The incisions are continued onto the middle of the vestibular wall and extended caudally to the labia. The cut edges are freed from the deep submucosa by dissection to create mucosal/submucosal flaps. The opposing edges of the flaps are joined in a Y-shape by an inverting suture line to create a tunnel from the urethral orifice to the caudal vestibule. A sterile catheter can be placed in the urethra prior to performing the procedure to prevent damage to the urethral orifice and to provide a template. Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be given post-surgery, and the reproductive tract should not be examined for at least 2 weeks. Persistent hymen: This is more common in mares than in other domestic species. Aetiology: The hymen may be imperforate or may be present because the caudal section of the paramesonephric duct failed to fuse with the urogenital sinus. Treatment: Treatment is by surgical excision after sedation of the mare. It is usually adequate to nick the membrane with a guarded blade and then extend the incision with the operator’s fingers. Secretions may accumulate cranial to the hymen. These secretions may infrequently become infected and result in infertility. • The embryo is mobile in the uterus until day 16 after ovulation. This mobility of the embryo may be necessary for maternal recognition of pregnancy because the mobile embryo inhibits PGF2α release. • The zona pellucida is shed at day 7, and the embryo is surrounded by a glycoprotein capsule. ‘Hatching’ from the zona pellucida, as seen in the cow, does not occur in the mare because the formed capsule retains the embryo’s spherical shape. The capsule persists until the fourth week of pregnancy. 3. Microcotyledonary. Attachment by microvilli does not occur until approximately 38 days. The macrovilli, which appear at day 45, are the forerunners of the microcotyledons. Maximum placental attachment does not occur until completion of the interdigitation of the placental microcotyledons at day 150. The uterine glands secrete ‘uterine milk’ throughout pregnancy.

Reproduction

14.1 The non-pregnant mare

Stages of the oestrous cycle

Dioestrus

Vernal and autumn transition stages

Examination of the mare for breeding soundness

Diseases of the mare’s reproductive tract

C Uterine tubes

D Uterus

E Cervix

F Vagina

14.2 The pregnant mare

Embryonic period

Placenta