Chapter 18 Raising Giant Tortoises

Only a few institutions have been successful in regularly breeding and raising giant tortoises. Knowledge of tortoise management and breeding remains scarce, and minimal scientific data exist. The published peer-reviewed data on the topic largely have been generated from Galápagos tortoises at one facility (Zurich Zoo, Switzerland). Although the author has taken great care to collect scientific data from as many sources as possible, large parts of this chapter still reflect personal observations. It is hoped that in the future this information will be subjected to scientific analysis to allow a transition from experience-based to evidence-based raising of giant tortoises.

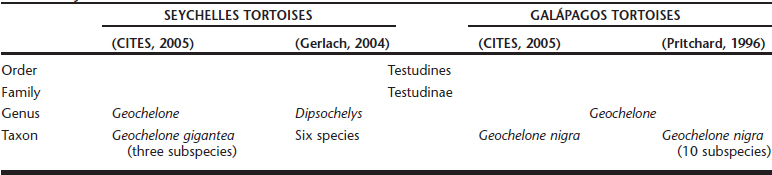

The order tortoises Testudines include the families Testudinae and Emydidae. The Testudinae comprise 14 genera. From fossils it is known that several Testudinae existed as giant forms on all continents except Australia and Antarctica. At present, giant tortoises have survived on Aldabra, the Seychelles, and the Galápagos Islands. The taxonomy of the surviving genera is still under debate; Table 18-1 summarizes the different nomenclature. This chapter uses the terms Geochelone nigra and Geochelone gigantea for Galápagos tortoises and Seychelles tortoises, respectively.

The current number of Galápagos tortoises is estimated at 12,000 to 15,00023 and the Seychelles tortoises at 100,000.1 All giant tortoises are listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora5: Seychelles tortoises are classified under Appendix II and Galápagos tortoises under Appendix I.

The major threat to giant tortoises is feeding concurrence by introduced domestic animals, especially goats, dogs, and pigs, as well as predation by rats. In addition, illegal trade still has a significant negative impact on population densities, especially in the Seychelles tortoises. In 2002, fewer populations of Galápagos tortoises were affected by food concurrence. Wild pigs and dogs on Santiago and Isabella Islands have been eradicated. The islands of Pinta Espa-ola and Santa Fe no longer have goats. Goats are still present on Isabela, Santiago, and San Crist-bal.18 Unfortunately, Galápagos tortoises face a new threat, which is habitat reduction. The archipelago prospers and has the highest overall standards of living of any province in Ecuador. This has caused massive increases of the human population on the islands. In an area where 95% of the land is a national park, this leads to conflicts.

UNIQUE ANATOMY

The two species of giant tortoises may readily be differentiated by the form of their head and the carapace Table 18-2. Adult giant tortoises may grow to a straight carapace length (sCPL) of more than 130 cm and a body weight of 300 kg. Seychelles tortoises are approximately 20% smaller and less heavy than Galápagos tortoises.

Table 18-2 Anatomic Differences between Galápagos (Geochelone nigra) and Seychelles (Geochelone gigantea) Tortoises

| G. gigantea | G. nigra | |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Head with similar diameter as neck | Head wider than neck |

| Rounded ridge of nose, pointed nose | Short nose | |

| Prefrontal scales | Large | Small |

| Nose | Vertical, slitlike opening | Round opening |

| Soft tissue flap on the nasal septum allows animal to close off the nasal cavity proper; drinking through nose possible. | No drinking through nose possible | |

| Nuchal scute | Present in 98% | Absent |

| Caudal scute | Mostly double | Single |

Modified from Ebersbach K: Doctoral thesis, Hannover, Germany, 2001, University of Hannover.

The general anatomy of giant tortoises is comparable to that of Testudines in general. Of special interest for breeding is gender differentiation. Adult animals may readily be differentiated externally based on plastron and tail. As in many other tortoises, adult males have distinctly longer tails than females, and the plastron is concave. Determining gender in hatchlings and juvenile giant tortoises, however, is not readily possible. One way to differentiate gender in Seychelles tortoises may be the number of tail scales. As the tail grows, the scales elongate, but new tail scales are not formed. Female Seychelles tortoises were found to have 8 to 11 scales, whereas males have 12 to 14 scales.10 This method has not been investigated in Galápagos tortoises.

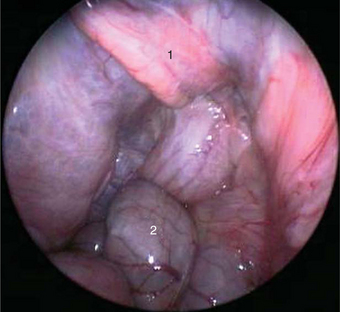

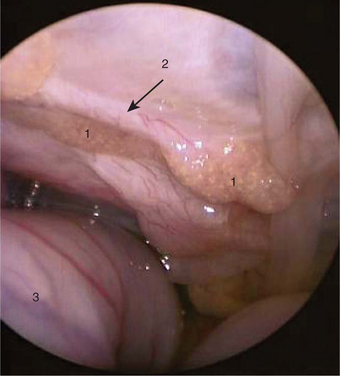

Endoscopic gender differentiation has successfully been performed in Galápagos tortoises ages 12 months and older. The ovary with primary follicles or the inactive testicle may readily be visualized Figures 18-1 and 18-2. Access with a 2.7-mm rigid endoscope, with a 30-degree distal lens offset, is from the left prefemoral region, as in other chelonians. Carbon dioxide is used for insufflation.

CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT OF GIANT TORTOISES

Because of their large body size, captive management of giant tortoises may be a challenge outside their natural climatic condition. The following describes the enclosure of Galápagos tortoises at Zurich Zoo, where successful breeding has occurred.15 Three adult and four juvenile animals are kept in a combined indoor (65 m2) outdoor (400 m2) enclosure. The outdoor enclosure has a 12-m2 shelter that offers constant temperatures of 27°C. The animals remain on the outside enclosure as long as night temperatures do not fall below 15°C.

The indoor enclosure has a 30-m2 heated surface (24°C). For oviposition a special nesting area has been prepared that measures 2 × 3 m. The depth is 50 cm, and it is filled with sand. This area is under 24-hour lapse-time video supervision during months when oviposition is expected. This allows safe removal of the clutch for artificial incubation. Special attention is given to the photoenvironment of the indoor space. A solarium with infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) light offers a local hot spot of 38°C twice daily for 30 minutes, usually after feeding. Special high-intensity mercury light sources are used, with the aim to expose the animals to full-spectrum light. By definition, “full spectrum” means a color temperature of 5500°K, a color-rendering index of 90 and above, and a spectral power distribution for UV as well as visible light similar to that of open-sky, natural light at noon. Relative humidity in the inside enclosure is 60% to 70%. Both inside and outdoor enclosures have a shallow pool, often used by giant tortoises. A mud wallow is not available but would be an important addition because giant tortoises readily use wallows. In our experience a mud wallow in the outside enclosure has the disadvantage that animals remain in the mud when temperatures drop, and it is then difficult to remove an adult giant tortoise without the risk of causing damage to the carapace.

NUTRITION

An evaluation questionnaire found that zoos keep Seychelles tortoises mainly on domestic fruits and vegetables, or grass, hay, and other roughage. Such a diet is not adequate. Giant tortoises are herbivorous, and their natural diet consists of grass, leaves, flowers, and fruits. In the wild, giant tortoises consume what is described as “tortoise turf,” a complex of grasses, sedges, and herbs.8 In Seychelles tortoises an apparent dry-matter digestibility of 30% was measured for the turf. Carnivory and coprophagia have been observed but do not make up more than 0.5% of the total ingested diet.

Giant tortoises are well adapted to a diet rich in fiber. Four captive-bred juvenile Galápagos tortoises ages 4 and 5 years were fed a controlled diet for 32 days. The diet consisted of 77% hay, 15% tortoise pellets, and 8% apples on a dry-matter basis. Diet analysis revealed 95.7% organic matter, 11.3% crude protein, 20.5% crude fiber, 22.6% acid detergent fiber, 5.0% acid detergent lignin, and 17.6% cellulose. Based on total fecal collection during 7 days, the following average dry-matter digestibilities were calculated: 65% for dry matter, 67% for organic matter, 63% for crude protein, 55% for crude fiber, 49% for acid detergent fiber, 41% for acid detergent lignin, and 54% for cellulose. Compared with mammalian hindgut-fermenting herbivore species (domestic horses, Asian elephants, Indian rhinoceroses) on a diet of hay and concentrates, the juvenile Galápagos tortoises showed a digestion of similar efficiency. An increase in crude fiber content resulted in a reduced digestibility. If a reduction in dietary digestibility is to be achieved in juvenile Galápagos tortoises, crude fiber levels of 30% to 40% on a dry-matter basis should be the target.13

Adequate calcium (Ca) supplementation is critical for the healthy development of giant tortoises. Oyster shell powder and calcium carbonate has successfully been added to the diet. In juvenile Galápagos tortoises, we found that an increased Ca-to-phosphorus (P) ratio did not result in a reduced Ca uptake.16 Apparent Ca digestibility at Ca/P levels of 4:1, 5:1, and 7:1 was 42%, 63%, and 82%; P digestibility increased as well. This was similar to mammalian hindgut fermenters, such as rabbits and horses, in which increased dietary Ca concentrations result in increased digestibility. Excessive Ca is excreted mainly through the urine. An optimal Ca/P ratio of 4:1 to 6:1 is recommended. Oversupplementation may result in Ca concrements in the bladder and could result in urolithiasis.

Frequent drinking of water was observed in Aldabran tortoises, and it is recommended that juvenile giant tortoises in general should always have access to water.4

BREEDING GIANT TORTOISES

Captive management of giant tortoises has a relatively long tradition in European zoos. In 1960 a census showed 30 Galápagos tortoises in 13 European collections, with the majority being males.15 The reason for this male dominance was that zoos were mostly interested in exceptionally large specimens. Because of the longevity of giant tortoises, this bias toward males still influences the gender ratio of the captive giant tortoise population. Management of these male-dominated groups was often unsatisfactory. In the summer the animals were kept outside and had barely heated shelters for colder days. In winter they were confined in small, overheated, humid shelters. Under these circumstances, it is surprising that the first successful breeding of Galápagos tortoises had already occurred in 1939 at North Miami Zoo and the Bermuda Aquarium. Since then, breeding of Galápagos tortoises has been successful at the San Diego Zoo (1958), Honolulu Zoo (1967), Philadelphia Zoo (1975), Gladys Porter Zoo (1986), Life Fellowship Bird Sanctuary Florida (1987), and Zurich Zoo (1989). It is only since the 1980s that some institutions have had regular breeding success. Between 1990 and 2003, Zurich Zoo raised 50 Galápagos tortoises.

Reports from the Seychelles Tortoise Conservation Project suggest that spatial and social variability plays an important role for successful reproduction. It is recommended that social groups should not be heavily male biased. One male should be significantly larger than the others to reduce aggressive encounters within the herd.10 There seems to be a hierarchy, with the largest male mating with the most females. Chida4 hypothesized that females with a carapace length more than 70 to 80 cm lose their breeding capability because they chose larger males, which at a certain carapace length would not be possible. Females must be able to avoid males, and male-male competition has been shown to stimulate breeding. Keeping large groups of at least 12 animals together appears to increase breeding activity. Best breeding was found where animals had much space (30 m2 per animal).

Ultrasound examination in Galápagos tortoises has shown that follicles became preovulatory at a diameter of 40 to 42 mm, and eggs were laid 34 to 84 days after thin-shelled eggs were detected in the oviduct.3 Eggs with shells may also be retained until the next breeding season, without adverse effects. Dystocia has not been reported, but the risk is certainly increased if no adequate area for oviposition is offered.

For successful artificial incubation of eggs, Seychelles tortoises need at least 80% humidity and temperatures of 28° to 31°C (82.4°-87.8°F). Temperatures above 29°C (84.2°F) appear to result in females.10 At temperatures between 28° and 30°C, incubation lasts 125 to 136 days, whereas at temperatures between 30° and 32°C (86° and 89.6°F), hatching takes place after 90 to 94 days. At hatching, Aldabran tortoises weigh 40 to 70 g and have a carapace length of 50 to 80 mm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree