Chapter 2 Rabbits

Consultation and handling

Rabbits are prey animals and, therefore, may exhibit extreme anti-predator behaviour, such as jumping from the examination table. During a clinical examination, movements should be moderated and deliberate with loud noises avoided as these may startle the rabbit. The scent of potential predators such as dogs, cats and ferrets may be stressful to some rabbits so these should be removed by cleaning your hands, examination table and equipment as best as possible prior to examination.

Table 2.1 The rabbit: Key facts

| Average life span (years) | 5–10 |

| Weight (kg) | 1.0 kg (Netherland dwarf) to 10 kg (giant breeds) |

| Body temperature (°C) | 38–39.6 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 30–60 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 120–325 |

| Gestation (days) | 28–35 |

| Age at weaning (weeks) | 4–6 |

| Sexual maturity (months) | 4.5–9 |

Nursing care

Thermoregulation

This is one of the most crucial homeostatic mechanisms for rabbits (and other small mammals). They are susceptible to both hyperthermia and hypothermia (which acts as a general depressant and is also immunosuppressive). Body temperature is achieved and maintained at some cost to the rabbit, which must generate and maintain a high metabolic rate. However, their small size means that they have a large surface area compared with body mass with a consequent high potential for conductive, convective and radiative heat loss. In the conscious rabbit, heat loss is countered by a variety of mechanisms such as dense coats and subcutaneous fat (insulative layers) plus physiological methods – peripheral vasoconstriction/dilatation, piloerection and shivering. Behaviour also alters to either enhance or reduce heat loss. High respiratory rates secondary to stress can mean a significant evaporative heat loss.

Management of hyperthermia (see Systemic Disorders)

Management of hypothermia

Fluids

In small mammals the choice of fluid used is as indicated with other mammals. Venous access in the rabbit is via the cephalic, lateral saphenous and marginal ear vein (Fig. 2.1). Jugular cut down can be undertaken under general anaesthesia (GA), but may result in respiratory embarrassment. Fluids can be given i.v. either by bolus or by infusion.

In hypovolaemic patients vascular access may be impossible and it may be better to consider either i.p. or i.o. administration. For i.o. it is relatively simple under GA to insert either an intraosseous catheter or a hypodermic needle into the marrow of either the femur (via the greater trochanter) or tibia (through the tibial crest). Fluids, colloids and even blood can be i.o. if necessary.

Nutritional support

Many rabbits are presented as emergencies after a prolonged period of ill-health that will have affected their food intake, e.g. suffering from undiagnosed chronic dental disease. These animals are often hypoglycaemic, so testing beforehand (a commercial glucometer is suitable) is beneficial, followed by i.v. or i.p. glucose to those cases identified.

Analgesia

Table 2.2 The rabbit: Analgesic doses

| Analgesic | Dose |

|---|---|

| Buprenorphine | 0.01–0.05 mg/kg s.c., i.m., i.v. every 6–12 h |

| Butorphanol | 0.1–1.0 mg/kg s.c., i.m., i.v. every 2–4 h |

| Carprofen | 1.0–2.0 mg/kg s.c. or p.o. b.i.d. |

| Ketoprofen | 1.0 mg/kg i.m. b.i.d. |

| Meloxicam | 0.1–0.3 mg/kg s.c. or p.o. s.i.d. |

| Morphine | 2.0–5.0 mg/kg s.c. or i.m. every 4 h |

| Pethidine | 5.0–10 mg/kg s.c. or i.m. every 2–4 h |

| Nalbuphine | 1.0–2.0 mg/kg i.m., i.v. every 2–4 h |

Anaesthesia

Masking with volatile anaesthetics alone

The advantage of this technique is rapid recovery without the need to metabolize large amounts of drug, both of which can be important with rabbits that are catabolic, e.g. with chronic dental disease. Isoflurane appears to be less stressful for induction than halothane, based on lower corticosterone levels (González-Gil et al 2006).

Gaseous anaesthetic induction protocol

Skin disorders

Satin breeds have altered hair fibre structure.

Findings on clinical examination

Investigations

Management

Treatment/specific therapy

Investigations

Treatment/specific therapy

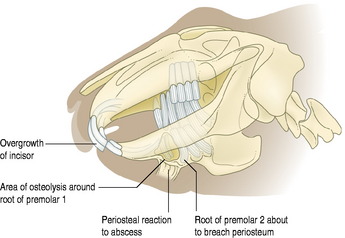

Dental disorders

Findings on clinical examination

Investigations

Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree