Chapter 8 Snakes

Snakes are popular reptile pets, and there has been a resurgence in their popularity with the breeding of a variety of colour morphs. A huge number of species are available in the pet-trade, but the commonly kept species are listed in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Commonly kept species of snake: Key facts

| Species | Notes | Common disorders |

|---|---|---|

| The royal python (Python regius) | This is a small python, growing to 90–120 cm. It has a not undeserved reputation for prolonged fasting, probably as a result of poor husbandry and endogenous cycles, although this is less pronounced with the modern captive-bred individuals and colour morphs | Dermatitis, dysecdysis and pneumonia. Anorexia, especially in wild caught or captive farmed individuals |

| The Burmese python (Python morulus bivittatus) | This python is a potentially very large snake; adults can reach up to 5–7 m long with a large muscular cross-section. Adults are usually reasonably behaved but hatchlings and youngsters can be aggressive | Dysecdysis, burns, pneumonia, inclusion body disease (IBD) |

| Boa constrictor (Constrictor constrictor) | A large snake up to 1.8–3.0 m long. Usually handleable but some individuals can be aggressive. Several colour morphs available and there is some selective breeding to reduce size using naturally occurring dwarf island subspecies | Snake mites, dysecdysis, inclusion body disease (IBD) |

| Corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata) | Moderate-sized rodent-eating snakes that make excellent introductions to snake-keeping. This is probably the nearest there is to a domestic snake; it is available in a very wide range of colour morphs, grows to a manageable size (around 1.0 m) and readily takes frozen-defrosted prey | Dysecdysis, cryptosporidium |

| King snakes (Lampropeltis spp) | King snakes are natural predators of snakes and other reptiles and so are usually kept individually | Dysecdysis, obesity |

| Garter snakes (Thamnophis spp) | Small to medium-sized snakes. Can be nervous on handling. Many of these are earthworm, fish and amphibian predators, although they can be readily converted on to mammalian prey | Septicaemia, thiamine deficiency |

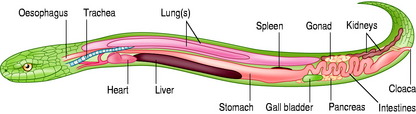

The internal anatomy of a snake is shown in Figure 8.1 (see also ‘Radiography’, in Musculoskeletal Disorders).

Consultation and handling

Microchipping

Sexing

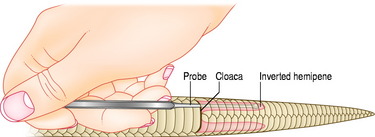

Many snakes are not obviously sexually dimorphic or dichromatic. The safest and most popular way of sexing monomorphic snakes is by ‘probe-sexing’, where a small, well-lubricated and blunt-ended rod is gently inserted into the cloaca and then directed caudally to one side of the midline so as to slot into the inverted hemipenes of the male, if present. If female, the probe will only travel a few subcaudal scales, while in a male it will pass a significant distance (Fig. 8.2).

Nursing care

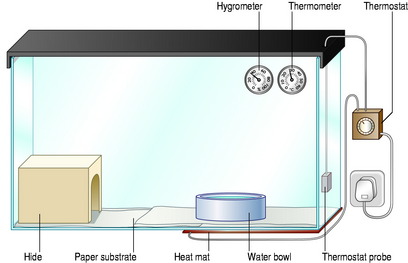

Provide an appropriate environment, including provision of:

Fluid therapy

See ‘Fluid Therapy’, in Lizards.

Skin disorders

Normal ecdysis in snakes

Differential diagnoses of skin disorders

See also Skin Disorders, in Lizards

Erosions and ulceration

Nodules and non-healing wounds

Findings on clinical examination

Treatment/specific therapy

Respiratory tract disorders

Findings on clinical examination

Investigations

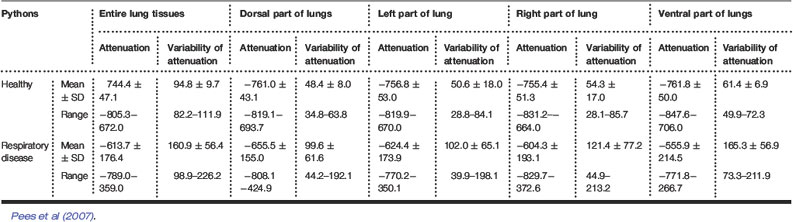

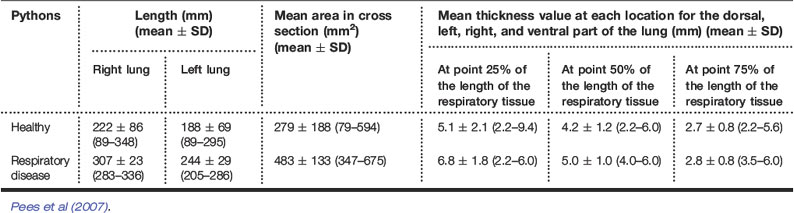

Table 8.2 Measurements for CT examinations of the lungs of healthy Indian pythons (Python molurus) and pythons with respiratory tract disease

Treatment/specific therapy

Gastrointestinal tract disorders

Findings on clinical examination

Treatment/specific therapy