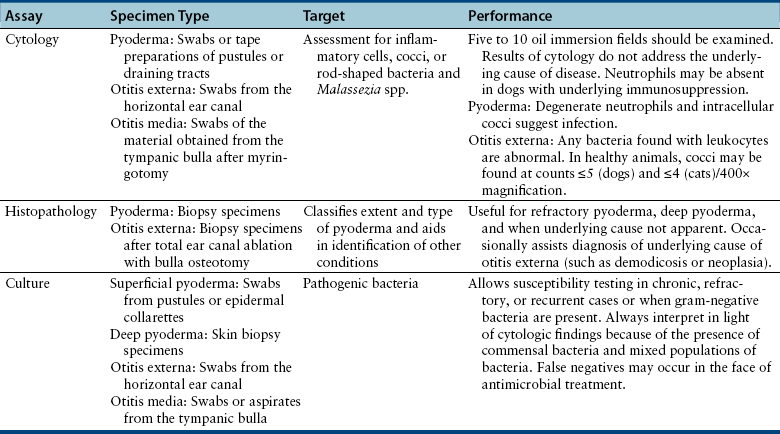

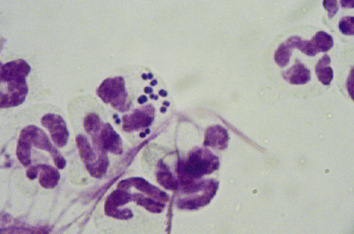

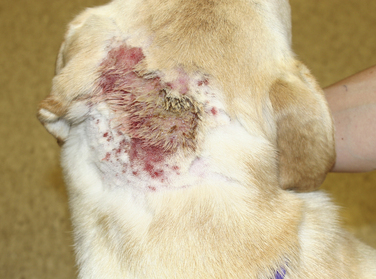

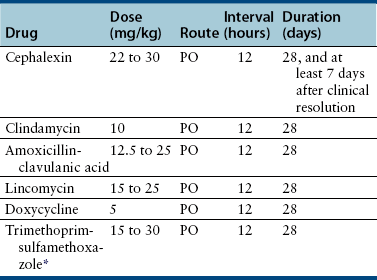

Chapter 84 Surface pyoderma occurs when bacteria proliferate on the surface of the skin and incite an inflammatory response, without invading the skin. Surface pyodermas include the “fold” pyodermas (also known as intertrigo), “hot spots” (also known as pyotraumatic dermatitis), and mucocutaneous pyoderma, which commonly affects German shepherd dogs.1 The last probably has an immunologic as well as a bacterial etiology. Mucocutaneous pyoderma is histologically identical to intertrigo, and differentiation between the two entities must be made clinically.2 Microbial overgrowth has also been categorized as a surface pyoderma when it involves bacteria (as opposed to just Malassezia spp.). In superficial pyoderma, bacteria infect the superficial epidermal layers that lie immediately under the stratum corneum (the outermost layer of the skin) and the portion of the hair follicle above the sebaceous duct (the infundibulum) (Figure 84-1). This is the most common type of pyoderma. It includes superficial bacterial folliculitis, superficial spreading pyoderma, and “puppy pyoderma” (also known as impetigo or juvenile pustular dermatitis). FIGURE 84-1 Superficial bacterial folliculitis manifested by severe erythema, epidermal collarettes, pustules, papules, and plaques in a 10-year-old female spayed pit bull terrier cross dog with underlying atopic dermatitis. Cytologic examination showed numerous cocci and neutrophils. Culture and susceptibility grew a methicillin-susceptible, β-lactamase–producing Staphylococcus pseudintermedius that was treated successfully with cephalexin together with management of the underlying atopic skin disease. Deep pyoderma is defined by infection deep within the hair follicle, with or without follicular rupture (furunculosis) (Figure 84-2) German shepherd dogs seem prone to a more severe and extensive form of deep pyoderma.3 Other examples include pedal folliculitis and furunculosis, pressure-point pyoderma, pyotraumatic folliculitis and furunculosis, and muzzle folliculitis and furunculosis (“canine acne”). FIGURE 84-2 Deep pyoderma in a 2-year-old male neutered Labrador retriever. Cytology showed numerous cocci and neutrophils. No mites were detected in a skin scraping. The most common cause of pyoderma in dogs is the coagulase-positive Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (previously misidentified as Staphylococcus intermedius) (see Chapter 35 for more information on staphylococci).4 S. pseudintermedius is a normal resident of mucosal sites such as the anus and nares and is thought to colonize the skin transiently following grooming and excessive licking in dogs with pruritus.5 In contrast, the resident flora of the canine skin includes coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus spp., α-hemolytic streptococci, aerobic coryneforms, Acinetobacter spp., and some anaerobes. Other organisms implicated in canine pyoderma are Staphylococcus schleiferi and, uncommonly, Staphylococcus aureus.6–8 Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus spp., and Escherichia coli may be isolated from dogs with deep pyoderma.9,10 These organisms are thought to invade secondary to alteration of local environmental conditions by S. pseudintermedius. Complete genome sequencing of S. pseudintermedius isolated from a dog with pyoderma has shown that S. pseudintermedius possesses a number of virulence factors that resemble those produced by S. aureus.11 Over the past 5 years, clonal spread of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius has occurred across Europe and North America.12 Methicillin resistance has also been described among S. schleiferi and S. aureus isolates from dogs with pyoderma.8 These organisms encode an altered penicillin binding protein that incurs resistance to all β-lactam antimicrobials, and many also demonstrate resistance to fluoroquinolone antimicrobials. Surface pyoderma is usually caused by superficial skin trauma, such as the rubbing together of lip, facial, vulvar, and tail folds in dogs with skinfold pyoderma. “Hot spots” occur secondary to self-trauma, such as that secondary to flea allergy dermatitis, and are commonly found in the lumbosacral area. Clinical signs include erythema, variable pruritus, alopecia, moist exudation, and a foul odor. Chronic lesions may be characterized by lichenification and hyperpigmentation. The exact causes of mucocutaneous pyoderma and surface microbial overgrowth have not yet been elucidated. Mucocutaneous pyoderma is characterized by erosions and ulcerations with or without crusting, which involve the lips, nasal planum, nares, perioral skin, and sometimes the anus, vulva, prepuce, and eyelids. It has also been reported in the axillary and inguinal region.1 Microbial overgrowth syndrome usually involves the ventral aspect of the body and is characterized by erythema, pruritus, a foul odor, erythema, alopecia, hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and excoriations, but no evidence of papules, pustules, epidermal collarettes or crusts.13 Early lesions of superficial pyoderma are erythematous follicular papules (papules from which a hair shaft protrudes). As pus accumulates within the epidermis and hair follicles, these lesions become pustules. Papules and pustules are primary skin lesions. When pustules rupture, crusted papules result. Epidermal collarettes are circles of epidermal scale with a free edge facing toward the center of the circle (see Figure 84-1), and may be remnants of ruptured papules. In thick-coated or shaggy dogs, the scale may become trapped throughout the haircoat as epidermal collarettes exfoliate. Hair fragments are shed from damaged follicles, which results in alopecia. Crusted papules, epidermal collarettes, and alopecia are secondary lesions. Impetigo generally occurs in dogs less than a year of age. In impetigo, pustules are confined to the epidermis, without follicular involvement, and are most commonly found in the poorly haired (glabrous) areas on the ventral abdomen and inguinal region and around the chin. Superficial bacterial folliculitis usually occurs secondary to underlying allergic or atopic dermatitis or endocrinopathies such as hyperadrenocorticism or hypothyroidism. Pruritus is less common in dogs with underlying endocrinopathies. Other conditions that predispose to pyoderma include cornification disorders, genetic skin disorders, and ectoparasitism. In dogs with atopic dermatitis, invasion of the skin by staphylococci can in turn lead to a hypersensitivity response to staphylococcal antigens, which exacerbates the pyoderma.14 Because the lesions of bacterial pyoderma are directly visible, in many cases, diagnosis can be made based on a thorough physical examination. Use of a hand lens may be helpful. In some cases, clipping of small areas of the haircoat may be required. This can help to identify epidermal collarettes in dogs with dry scale. Careful attention should be paid to the presence of follicular papules, pustules, crusted papules, epidermal collarettes, alopecia, nodules, fistulous tracts, and the presence or absence of pruritus (Box 84-1). The distribution of lesions should be noted because it can be a clue to underlying disease, such as demodicosis. In dogs with deep pyoderma, the skin may feel warm to the touch, and peripheral lymphadenomegaly may be detected. The diagnostic approach to pyoderma should involve confirmation of the presence of pyoderma and a thorough search for possible underlying causes. The differential diagnosis includes many diseases that predispose to pyoderma, such as demodicosis, dermatophytosis, and pemphigus foliaceus (see Overview). When crusting is present, cornification disorders should be considered, although crusting may also result from self-trauma. The presence or absence of Malassezia spp. must also be determined (Chapter 59). In addition to a thorough physical examination, diagnostic procedures that may be necessary include skin scrapings, cytologic examination, aerobic bacterial culture and susceptibility, and skin biopsy (Table 84-1). Dermatophyte culture is indicated when underlying dermatophytosis is suspected (see Chapter 58). Identification and subsequent treatment of underlying allergic skin disease may require additional testing such as intradermal skin testing, for which referral to a veterinary dermatologist should be considered. Cytology can be performed on tape preparations of the skin or smears made after swabbing pustules or draining tracts. Cytologic examination is essential in order to identify concurrent infection with Malassezia pachydermatis. Slides should be air-dried and stained with a modified Wright’s stain such as Diff Quik. The presence of cocci suggests S. pseudintermedius infection (Figure 84-3). Infection is supported by the presence of degenerate neutrophils and intracellular cocci. Inflammatory cells may be absent in dogs with underlying immunosuppressive disorders or those receiving glucocorticoid treatment. Factors to consider when treating dogs for pyoderma include the underlying disease present, the severity and extent of lesions, and the local prevalence of staphylococcal resistance. Veterinarians’ reliance on systemic antimicrobial drug treatment has been challenged by the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant staphylococci. Topical treatments that help to restore skin structure and function, as well as topical antimicrobial therapy, should be considered as alternatives.15 In dogs with mild disease, treatment aimed at the underlying disorder may be sufficient to resolve infection (see Prevention). Topical antimicrobial drugs and antiseptics result in high concentrations of drug at the skin surface that can overwhelm bacterial drug resistance mechanisms, and can be useful when pyoderma is limited to small areas of skin. Aside from having the potential to be messy, these drugs have minimal side effects and result in minimal exposure of bystander organisms (such as gut flora) to antimicrobial drugs. Examples of topical drugs with excellent activity against staphylococci include neomycin, gentamicin, polymyxin B, bacitracin, hydroxyl acids (such as acetic acid), novobiocin, and silver sulfadiazine. Mupirocin and fusidic acid are additional topical antimicrobial drug preparations that may also be useful for treatment of pyoderma that is restricted to small areas. Unfortunately, resistance to mupirocin and fusidic acid has been documented in methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates from humans.16,17 When pyoderma is severe, treatment with systemic antimicrobial drugs may be required. The drug selected for empiric treatment should be based on the local prevalence of resistance, and narrow-spectrum drugs that target staphylococci are preferable. Clindamycin, first-generation cephalosporins (such as cephalexin), and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid are reasonable first choices (Table 84-2). Other acceptable alternatives when the local regional susceptibility of S. pseudintermedius is known include doxycycline, trimethoprim- or ormetoprim-potentiated sulfonamides, lincomycin, and erythromycin. The use of third-generation cephalosporins for empiric therapy is controversial because their use in particular has been associated with selection for methicillin-resistant staphylococci in humans and they have the potential to select for resistant populations of gram-negative bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract.18 More research is required to determine whether this is also true in dogs and for all third-generation cephalosporins. When pyoderma is severe, and only when culture and susceptibility indicate the presence of multidrug-resistant staphylococci, the use of chloramphenicol, minocycline, doxycycline, third-generation cephalosporins, rifampin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, amikacin, or fluoroquinolones (such as enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, orbifloxacin, pradofloxacin, or ciprofloxacin) could be considered as indicated based on culture and susceptibility results. The use of fluoroquinolones in humans and dogs is a risk factor for selection of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius and also has the potential for selection of resistant populations of gram-negative bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. TABLE 84-2 Suitable First-Tier Drugs for Treatment of Superficial Pyoderma in Dogs ∗Concerns exist regarding idiosyncratic and immune-mediated adverse effects in some patients with sulfa drugs, especially with prolonged therapy. Baseline Schirmer’s tear testing is recommended, with periodic re-evaluation and owner monitoring for ocular discharge. Avoid in dogs that may be sensitive to potential adverse effects such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), hepatopathy, hypersensitivity, and skin eruptions. See also Chapter 8. When treatment of the underlying cause or use of topical therapy is unsuccessful in preventing recurrence of pyoderma, subcutaneous administration of autogenous bacterins or commercial bacterial antigens (such as Staphage Lysate, Delmont Laboratories, USA) may be beneficial in some dogs.19,20 These are generally given once or twice weekly (see Chapter 7). Although S. pseudintermedius prefers not to colonize humans, human infection has been reported occasionally, including among veterinarians.21–23 A methicillin-susceptible S. pseudintermedius was detected as a cause of endocarditis in a human patient,23 and methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius has been isolated from human patients with sinusitis.21 In all cases, pet dog contact was reported and suggested to be the source of infection. In one case, an isolate from the dog matched that isolated from the human as determined using pulsed field gel electrophoresis. In contrast, contact with human hospitals and children may be risk factors for acquisition of methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections by dogs, and S. aureus infections appear to be a reverse zoonosis. Colonization is generally transient in dogs and cats, so specific treatment to decolonize dogs and cats is not necessary.24 Two subspecies of S. schleiferi have been described: S. schleiferi subsp. coagulans, which is coagulase positive, and S. schleiferi subsp. schleiferi, which is coagulase negative. Although it may be carried elsewhere on the body, S. schleiferi subsp. coagulans has been isolated primarily from dogs with otitis externa and was reported as a cause of endocarditis in an immunocompromised human.25 Coagulase-negative S. schleiferi are thought to be a commensal of the skin of both humans and dogs, and although they are common contaminants, they can cause disease in both species.8,26 Frequent and proper hand washing using soap and water and disinfectant foams or gels is the number one practice that limits spread of these infections in human hospitals. Hands should be washed before and after handling each patient. Clean clothing should be worn and laboratory coats changed regularly. Attention must be paid to regular disinfection of other fomites such as stethoscopes, cell phones, rectal thermometers, computer keyboards and mice, calculators, and bandage scissors. Disinfectant wipes that contain alcohol or accelerated hydrogen peroxide can be used to clean these surfaces.

Pyoderma, Otitis Externa, and Otitis Media

Pyoderma

Clinical Features

Surface Pyoderma

Superficial Pyoderma

Physical Examination Findings

Diagnosis

Microbiologic Testing

Cytologic Examination

Treatment and Prognosis

Topical Treatments

Systemic Antimicrobial Drug Therapy

Prevention

Public Health Aspects

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree