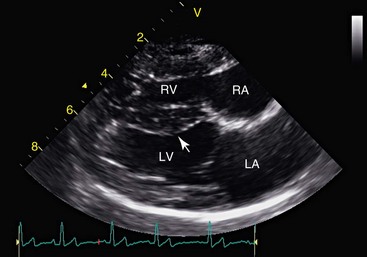

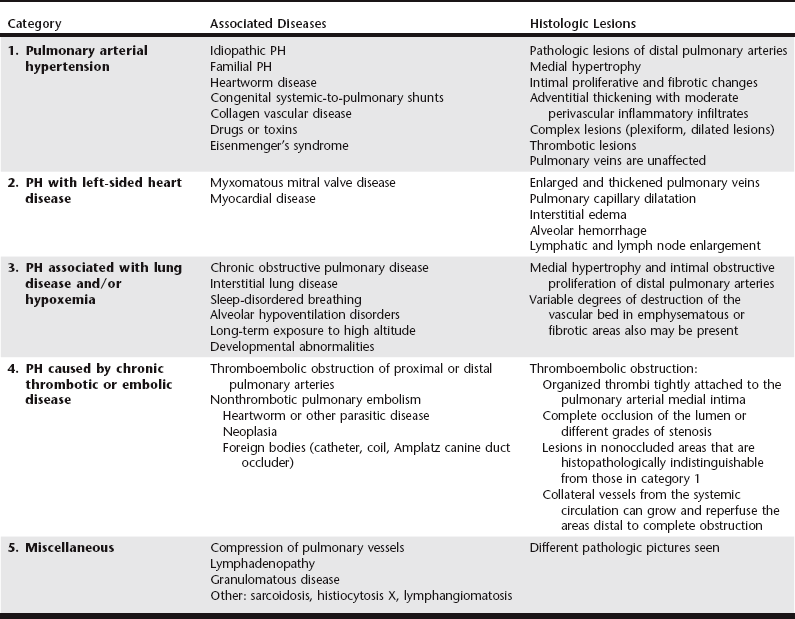

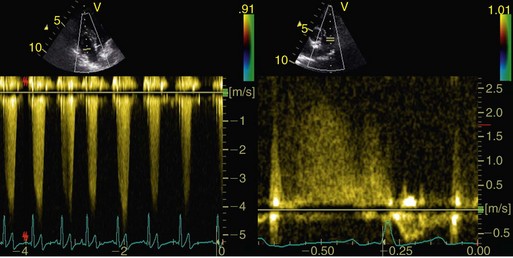

Chapter 167 The diagnosis of PH is confirmed by cardiac catheterization in human patients, but in veterinary medicine it is usually defined as an elevated systolic PA pressure as estimated noninvasively by Doppler echocardiography (Figure 167-1). Veterinary publications have used estimated systolic PA pressures of more than 31 mm Hg (up to 45 mm Hg) as indicators of PH. Despite publication of a number of clinical studies and reports, no consensus statements or prospective studies are available to definitively guide diagnosis or management of PH in dogs or cats. It should be noted that healthy dogs, as well as humans and other animal species, can reach much higher values of PA pressure while exercising, and this point certainly is relevant in animals with tachycardia that are undergoing Doppler echocardiographic examination. Figure 167-1 Continuous wave spectral Doppler tracings of a regurgitant tricuspid jet (left) and pulmonary insufficiency jet (right) in a dog with pulmonary hypertension caused by chronic respiratory disease. The maximum right ventricular to right atrial velocity is 4.2 m/sec and the pressure gradient is 73 mm Hg (see text), which suggests severely elevated pulmonary systolic pressure. The maximum pulmonary artery to right ventricular velocity is 2.4 m/sec and the pressure gradient is 23 mm Hg, which suggests elevated pulmonary artery diastolic pressure. PH is a well-recognized condition of dogs and has been described sporadically in cats. A variety of conditions and a spectrum of histopathologic lesions within the pulmonary vasculature lead to PH. Historically PH was classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary depending on the presence or absence of identifiable causes; however, more recently PH has been classified in relation to pathophysiologic mechanisms, histologic lesions, and therapeutic options. In dogs primary PH is a relatively rare condition. Although specific diseases commonly associated with PH in animals differ from those in humans, similar classifications can be devised (Table 167-1). Analysis of data from different case series encompassing a total of 197 dogs with PH of varying causes showed that the most common identified reason for PH was left-sided heart failure (category 2, 50% of cases). Primary lung disease (category 3) represented the second most common reason for PH (24% of cases). Diseases affecting the pulmonary arteries (pulmonary arterial hypertension, or category 1) were responsible for 10% of cases. Chronic thrombotic or embolic disease (category 4) was the cause of 9% of cases, whereas category 5—a compilation of miscellaneous conditions—was last, accounting for 7% of cases. TABLE 167-1 Clinical Classification, Associated Diseases, and Histologic Lesions of Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) in Dogs Adapted from Galiè et al: Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension, Eur Respir J 34:1219, 2009; and Henik RA: Pulmonary hypertension. In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC, editors: Kirk’s current veterinary therapy XIV, St Louis, 2009, Saunders, p 697. The most commonly identified reasons for PH in each category were as follows: heartworm disease and congenital systemic-to-pulmonary shunts for category 1; myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) and dilated cardiomyopathy for category 2; pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, chronic bronchial disease, and tracheal collapse for category 3; heartworm disease and pulmonary thromboembolism for category 4; and neoplasia for category 5 (Bach et al, 2006; Guglielmini et al, 2010; Johnson et al, 1999; Kellum and Stepien, 2007; Pyle et al, 2004). Commonly performed diagnostic tests include thoracic imaging, echocardiography (see later), and diagnostic tests for pulmonary parenchymal diseases or vascular diseases. The latter may include arterial blood gas analysis, cytologic analysis and culture of respiratory secretions, fine-needle aspiration or biopsy of the lung, and routine hematologic testing. Tests for heartworm disease are usually indicated in cases of suspected PH. Diagnostic tests for coagulopathy, such a platelet count, D-dimer level, and thromboelastography (see Chapter 15) may be useful to exclude or support a diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism. Echocardiography is usually the diagnostic test of choice for PH and is discussed later. The noninvasive gold standard for the diagnosis of PH in veterinary medicine is Doppler echocardiography (Figures 167-2 and 167-3; see Figure 167-1). This method also can establish the diagnosis of PH due to primary cardiac disease. It should be stressed that the diagnosis of PH in veterinary medicine is based on a combination of clinical and echocardiographic signs, and a single observation or variable cannot be relied upon. Figure 167-2 Right parasternal four-chamber long axis view in mid-diastole in a dog with severe pulmonary hypertension. A mixed concentric-eccentric hypertrophy pattern of the right ventricle is present. The interventricular septum (arrow) bows into the left ventricle, which decreases left ventricular size. LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Definition and Classification

Diagnosis and Clinical Presentation

Diagnostic Tests

Doppler Echocardiography

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pulmonary Hypertension

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue