Chapter 5 Primary Causes of Ear Disease

By definition, otitis externa represents a spectrum of inflammatory changes that occur to the external acoustic canal in response to any insult to the ear canal epithelium. But what actually causes ear diseases? Can putting a bacterium or a yeast organism into a normal ear canal result in disease? Although there may be bacteria or yeasts found in the patient with otitis externa, these organisms are not the cause of the ear disease. The real reason for the ear disease is often overlooked. Primary causes of ear disease are those diseases of the skin that also have a direct effect on the skin lining the ear canal. Cutaneous diseases such as atopy, food hypersensitivity, parasites, foreign bodies, hypothyroidism, and seborrheic diseases frequently result in ear disease.

Atopic Dermatitis

It has been estimated that almost 75% of all canine ear disease is related to atopic dermatitis. Atopy seems to be prevalent in many breeds, giving evidence that this disease may have a genetic origin. Most dogs show clinical signs after the first year of life. Atopic patients probably have a high immunoglobulin E (IgE) response from B-lymphocytes when exposed to individual allergens. IgE antibody binds to mast cells resulting in their degranulation and subsequent release of inflammatory mediators on subsequent exposure to that specific antigen. Often there will be a history of foot licking or chewing, face rubbing, and licking the groin area, in addition to scratching the ears. Many dogs with light-colored coats have the telltale red-orange saliva staining typically found with atopy. Cats may manifest their atopic dermatitis with miliary dermatitis, facial pruritus, or barbering of their hair on the belly and lower legs with their teeth in response to the pruritus. Often dental disease will accompany a pruritic skin disease as hairs get trapped between the teeth and in the gingival sulcus, resulting in gingivitis. Atopic dogs also frequently have secondary bacterial and yeast infections on their skin and in their ears.

Many patients get rapid relief from their ear disease when the atopic dermatitis is treated with corticosteroid therapy, systemically and/or topically. Most combination otic formulations contain corticosteroids to relieve the inflammation and pruritus in the ear. A new therapy for atopic dermatitis using oral cyclosporine-A–modified capsules (Atopica, Novartis) relieves the pruritic clinical signs without the side effects often seen with corticosteroids. Other dogs and cats get long-term benefit from successful immunotherapy to specific antigens identified through allergy testing. It is important to discuss atopic dermatitis as a cause of ear disease with clients so that they understand the value in pursuing a proper diagnosis. After the otic inflammation resulting from atopic dermatitis is controlled, the ear canal epithelium is not as likely to support bacterial or yeast growth, and the patient can remain comfortable.

Food Allergy

Another common primary cause of canine and feline ear disease is food allergy. Termed “cutaneous adverse food reactions,” many components of this syndrome have a direct effect in the ear canal. Allergies in animals tend to become additive—that is, the severity of the clinical signs increases as the patient is exposed to more and more allergens, such as pollens, molds, insects, and foods. When the total antigen exposure is in excess to the tolerable antigen load, clinical signs develop. Some allergic animals can be controlled with a reduction in allergens. It is not uncommon to do a food trial with a hypoallergenic diet for 2 or 3 months with resultant reduction in otic signs. See Chapter 6 for a discussion of cutaneous adverse food reactions.

Ear Mites

A unique result of Otodectes infestation in the cat is a systemic hypersensitivity reaction. Known as otodectic mange, this skin disease resembles miliary dermatitis, a papular, crusty eruption found around the neck and head, dorsolumbar area, and inguinal area. When an ear mite–infected cat sleeps with its ear in the flank, the ear mites can leave the ear canal and get on the skin. A similar transfer occurs when an infected cat scratches the ear and the mites get on the paw. Those mites in an ectopic location migrate along the skin and feed. This results in a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite antigens absorbed across the damaged epithelium. Experimentally, infected cats showed an immediate hypersensitivity reaction to an intradermal mite extract. Cats infected for 35 days showed an Arthus (Type III) reaction. Serum precipitating antibodies were noted 45 days after infection. When cats with miliary dermatitis do not respond to systemic steroids, such as methylprednisolone acetate (DepoMedrol, Pfizer), or to flea-control measures, otodectic mange should be considered and the cat should be treated for Otodectes using a systemic acaricide such as ivermectin, fipronil, or sealmectin.

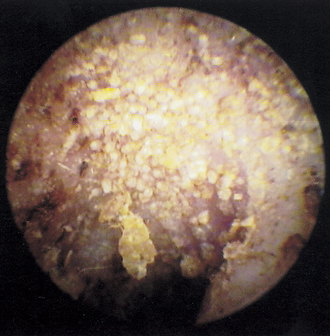

If the otoscope is held very steady, the mite activity increases, because the light arouses the mites and makes them more active. When viewed with a video otoscope (Video Vetscope, MedRx, Inc., Largo, Florida), which has a high magnification and a bright light source, the mites can often be seen in colonies, with thousands of mites scurrying about (Figure 5-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree