Chapter 16 Inflammatory Polyps

Signalment and History

Nasopharyngeal or inflammatory polyps originate from the eustachian tube or from the middle ear mucosa. Most of these polyps have their origin in the middle ear; however, when they originate in the eustachian tube, growth is usually directed toward the throat. Nasopharyngeal polyps can be found exiting the eustachian tube on the lateral wall of the oropharynx, beneath the soft palate. Retraction of the soft palate with a spay hook reveals their presence. The cat with an oropharyngeal location of its polyp shows respiratory symptoms such as stertorous respiration, voice changes, wheezing, dyspnea, and dysphagia.1

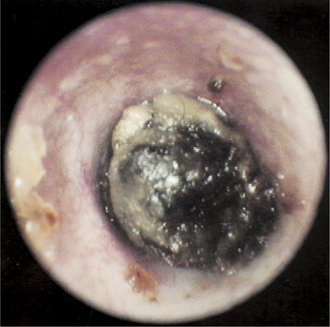

Several presentations can be seen when a cat has a polyp in the ear canal. Some cats with an aural polyp are presented to the veterinarian with a waxy accumulation deep in the ear canal (Figure 16-1). This may look similar to a ceruminolith or wax plug. The polyp mass cannot be visualized because it is under the wax.

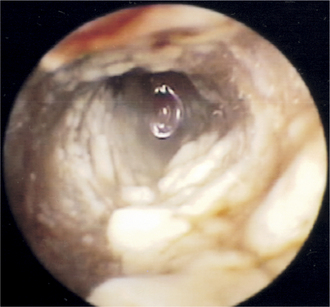

Some cats have dried, crusty material in the ear, similar to the discharge seen in Otodectes infections. The middle ear mucosa is a respiratory epithelium capable of producing copious amounts of mucus when it is inflamed. The mucus and pus that leak from the bulla into the external ear canal can dry out and become flaky, giving the impression that the cat has ear mites. More commonly, cats with polyps have a copious mucopurulent discharge in the affected ear due to liquid exudates filling the ear canal (Figure 16-2).

Figure 16-2 Liquid mucus and pus filling the ear canal of a kitten. After flushing the ear canal, the polyp was revealed (see Figure 16-4).

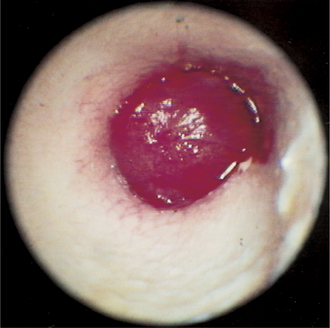

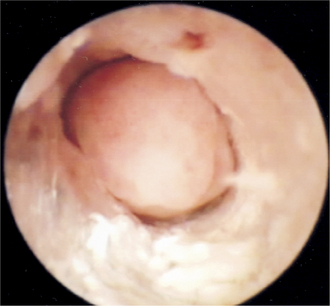

After cleaning the cat’s ear, otoscopic examination reveals a pink to red, fleshy, mobile mass deep in the ear canal (Figures 16-3 and 16-4). When the mass is visible in the external ear canal, it has already protruded through the eardrum, having ruptured it as the polyp grew outward from the tympanic bulla. When this happens, a secondary otitis media can develop as bacteria gain access to the middle ear mucosa.

Figure 16-3 Nasopharyngeal polyp occluding the ear canal of a cat. The waxy accumulation in Figure 16-1 was removed to reveal this red, fleshy mass in the cat’s ear canal.

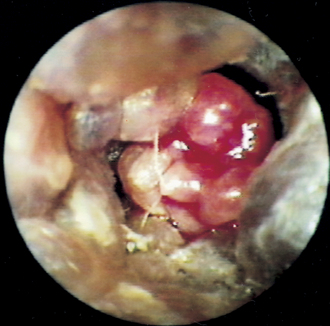

Figure 16-4 After the mucus and pus were removed from the ear canal from the cat in Figure 16-2, this fleshy mass was evident and could be pushed back into the middle ear. No eardrum is present in cats with polyps.

Manipulating the polyp mass often causes the release of material from the bulla into the external ear canal because the polyp acts as a seal for these middle ear exudates. Polyps can become quite large and may reach the diameter of the ear canal, effectively forming a plug that seals in the secretions in the bulla under it.

Microbiology

Many kittens and grown cats have unrecognized middle ear disease often as a sequela to upper respiratory disease. Otitis media is a consistent feature when nasopharyngeal polyps are found in the ear canal. Many bacterial pathogens have been cultured from the middle ear after bulla osteotomy including Pasteurella, streptococci, staphylococci, and occasionally Bacteroides and Pseudomonas.2 Some bacteria isolated from the middle ear in cats with polyps originate from the upper respiratory mucosa, and some pathogens originate from the external ear canal epithelium. Routine aerobic cultures for respiratory pathogens rarely include Mycoplasma, Bordetella, or Chlamydia, which may be involved in respiratory disease and middle ear disease of cats.3 It was once thought that viruses played a role in development of polyps. In one study, tissues from inflammatory polyps were assayed for feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus–1 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Failure to detect either of these viruses suggests that the persistence of these viruses is not associated with the development of inflammatory polyps.4 In another study, polyps were induced in rats by placing type 3 pneumococci into one middle ear cavity of each rat. In 44% of the rats a polyp developed in the experimentally infected ear. None of the rats developed a polyp in the untreated ear.

The sequestered inflammation and infection lead to changes in the middle ear mucosa. It is theorized that the chronic irritation of the middle ear mucosa leads to the formation of polyps. Initially there is a rupture in the respiratory epithelium lining the tympanic bulla or the eustachian tube, followed by intraluminal protrusion of the lamina propria through the epithelial defect. Then the respiratory epithelium covers this protrusion. As the epithelium covering the polyp becomes damaged by infection or by the physical trauma of its own movement against the surrounding tissue, this process repeats a number of times, resulting in significant production of fibrous stroma and enlargement of the mass. Often the mass becomes lobulated (Figure 16-5).

Figure 16-5 Multilobulated polyp in a cat. This type of polyp is usually more vascular than solitary-lobed polyps.

Depending on their growth pattern, polyps can grow through the auditory tube toward the nasopharnx or they may grow through the tympanic membrane. When found in the external ear canal, the enlarging polyp mass has grown through the tympanic membrane, creating a permanent opening from the external ear canal to the middle ear. The middle ears of these cats have copious mucus and pus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree