Chapter 4 Diagnostic Imaging of the Ear

Selecting the appropriate imaging method, correctly applying the technique selected, and accurately interpreting the examination are the key steps in imaging ear disorders in dogs and cats. Conventional screen-film radiography (including positive contrast canalography), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered complementary techniques, since no single imaging modality perfectly depicts the complex anatomy of the ear. The physics and instrumentation that form the basis of these diagnostic procedures will not be discussed. This chapter provides an overview of the indications for and limitations of different modalities, emphasizing the key points in selecting and performing the appropriate studies and interpreting the images. Readers will find the information needed to decide which modality will be most effective in a specific clinical setting. One guideline applies to all imaging described here—general anesthesia is required for a full assessment of the middle and inner ear. Attempting to evaluate these areas with sedation alone or without chemical restraint is an exercise in futility.

Conventional Radiography

Lateral View

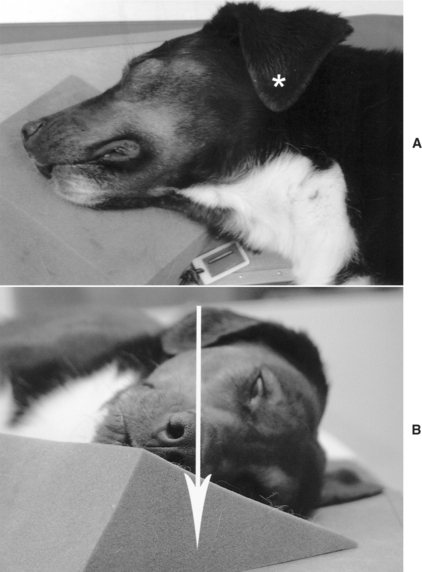

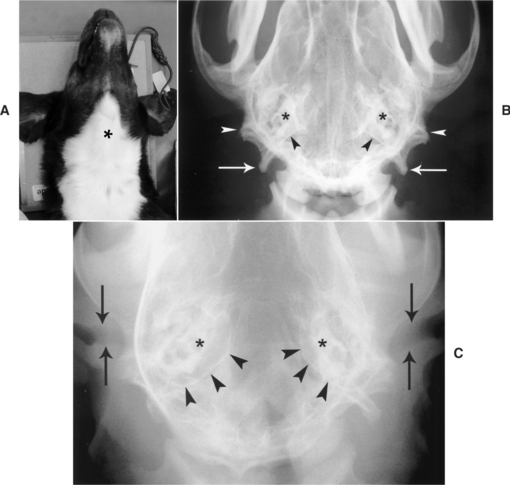

The animal is placed in lateral recumbency with the nasal septum parallel and the hard palate perpendicular to the tabletop cassette (Figure 4-1, A and B). The primary beam is centered on the external acoustic canal. A foam wedge or gauze roll placed beneath the rostral third of the nose is needed to maintain proper alignment. The head should be slightly extended to avoid superimposition of the bullae on the pharynx. Portions of the larynx and pharynx should be included in this view (Figure 4-1, C) to assess the temporomandibular joints and the nasopharynx because as some diseases, such as nasopharyngeal polyps and craniomandibular osteopathy, can also affect the middle ear. This author prefers a subtle rostral offset of one bulla from the other to compare them. To achieve this, the primary beam can be centered just rostral to the external acoustic meatus, or the rostral third of the nose can be elevated slightly from parallel to the cassette (Figure 4-1, D). In animals with a large pinna covering the acoustic canal, such as hound or spaniel breeds, the pinna should be unfolded and placed dorsal to the skull to avoid allowing skin artifacts to obscure the area of interest. The endotracheal tube can be left in place. The external acoustic meatus is a circular to oval, gas-filled structure with well-defined inner borders. The tympanic bullae have smooth, thin-walled bone margins and a gas-filled lumen (see Figure 4-1, C and D). Thickness of the wall varies between breeds. There is less variation in the thickness of the bullae walls between breeds in cats. The petrosal portions of the temporal bones are highly radiopaque and superimposed on each other in this view; therefore, they cannot be fully assessed. In cats the bullae appear larger in proportion to the head than in dogs.

Oblique Views

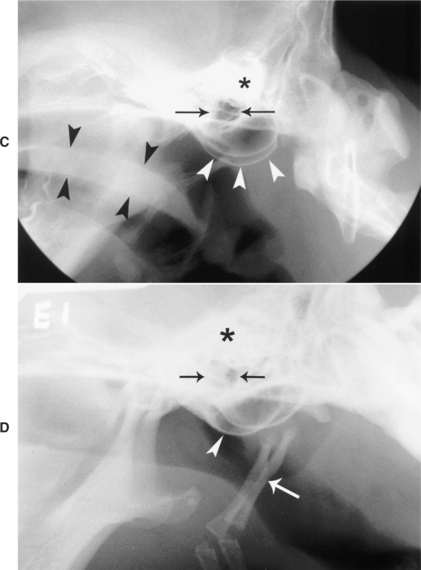

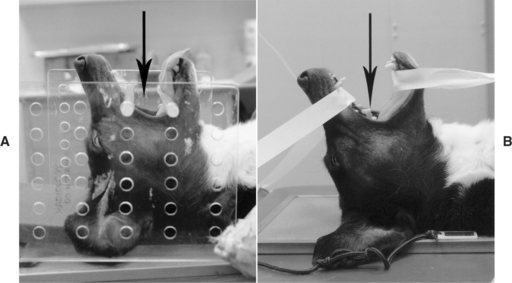

Two opposite oblique views are taken. With the animal in lateral recumbency, the bulla to be imaged is placed closer to the cassette. The thoracic limbs, sternum, nasal cavity, and mandible are rotated 20 degrees from the horizontal plane and are held in position with foam wedges (Figure 4-2, A and B). The mouth is closed to avoid superimposition of the mandible on the area of interest. The primary beam is centered at the base of the ear, ventral to the tragus. The primary beam travels through the patient in a lateral 20-degree ventral–left dorsal oblique direction. The tympanic bulla to be assessed is projected ventrally, while the contralateral bulla is superimposed over the caudal third of the calvarium and therefore cannot be assessed fully (Figure 4-2, C). Portions of the stylohyoid bone may be superimposed over the bulla of interest. The tympanic bullae have smooth, thin-walled bone margins and a gas-filled lumen. The external acoustic meatus is projected on the bulla as a circular to oval, gas-filled structure with well-defined inner borders.

VD and DV Projections

Choosing between a DV and VD projection is more a function of hospital protocol or personal preference than clinical need. To obtain the VD view, the animal is placed in dorsal recumbency. The primary beam enters the patient in a VD orientation at the midline halfway between the external acoustic meatuses (Figure 4-3, A). The animal is placed in sternal recumbency to obtain a DV view. The primary beam is directed vertically centered at a point where an imaginary line connecting the bullae intersects with the midsagittal plane. The body of the mandible should be parallel to the cassette, to avoid distortion. The tongue should be pulled forward and maintained on the midline. These views are used to assess the ear canals and to compare symmetry of the bullae and the petrosal portion of the temporal bones. The tympanic bullae cannot be evaluated fully in this view because they are superimposed over the petrosal portions of the temporal bones (Figure 4-3, B). There is no specific bone pattern associated with the petrous temporal bones, however; they should exhibit a symmetrical shape, size, and opacity on these projections. Reducing the milliamp seconds (mAs) by half to highlight the soft tissues allows visualization of the horizontal portion of the external acoustic canals (Figure 4-3, C), which are noted as well-defined lucent structures. The canals tend to be wider laterally as the auricular cartilage expands to form the pinna. The average diameter of the proximal end of the annular cartilage is 4.1 ± 0.7 mm in dogs in which the tympanic membrane is visible otoscopically.1

Open-Mouth View

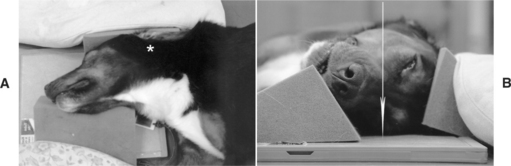

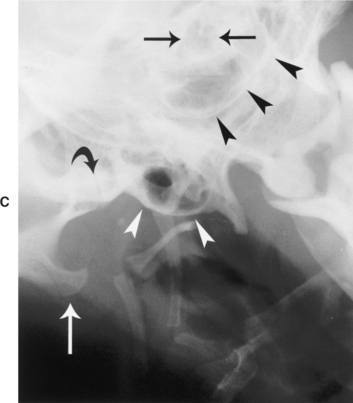

A commercially available U-shaped acrylic head rack can be used to facilitate positioning (Figure 4-4, A). Without a positioning device, medical-grade adhesive tape can be used to separate the mandible from the maxilla (Figure 4-4, B). With the animal in dorsal recumbency, the head is acutely flexed toward the thoracic inlet. The vertical primary beam is directed rostroventral to caudodorsal and centered immediately ventral to the hard palate. The hard palate and mandible are 30 degrees from the vertical plane. This will highlight both tympanic bullae with minimal superimposition from the surrounding structures. The endotracheal tube should be removed or secured against the mandible. To avoid increased bullae opacity due to superimposition, the tongue should be pulled rostrally and secured to the mandible on the midline. The normal bullae are noted as thin-walled structures with a lucent center ventral to the base of the skull (Figure 4-4, C). Increasing the angle of the hard palate relative to the primary beam can be used as an alternative to the open-mouth projection (Figure 4-4, D). This projection is easier to perform because it is a closed-mouth view that highlights the most caudal surface of the tympanic bullae. Caution should be taken in assessing abnormal findings on this projection because its clinical value has not been studied as extensively as the open-mouth view.2 Normal bullae are thin-walled structures with a lucent center ventral to the base of the skull (see Figure 4-4, C). Their walls are of uniform thickness. They are symmetrical in size, shape, and opacity when compared with one another.

In cats an osseous septum divides the bullae into two separate but communicating tympanic cavities—a smaller dorsolateral compartment and a larger ventromedial compartment (Figure 4-4, E). There is less variation in the thickness of the bulla walls between breeds in cats. The external acoustic meatus is sometimes superimposed on the dorsolateral compartment.

Abnormal Radiographic Findings

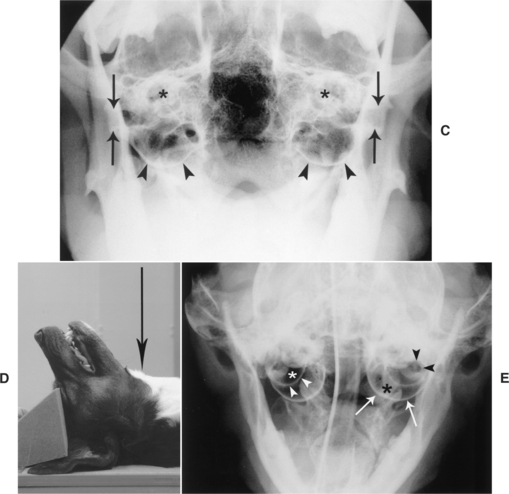

Otoscopic evaluation is the method of choice to evaluate the external ear canal. However, radiographs can reveal narrowing of its lumen by soft-tissue proliferation from extraluminal masses in cases of neoplasia or by inflammatory tissue, exudates, or debris in cases of otitis externa or trauma (Figure 4-5, A). Dystrophic calcification can be seen associated with chronic otitis externa (Figure 4-5, B).

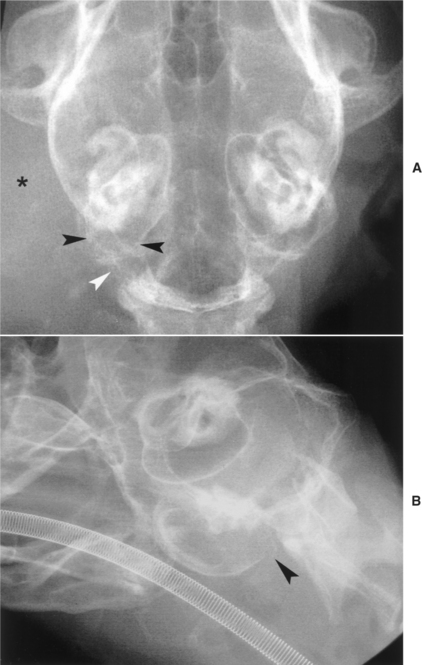

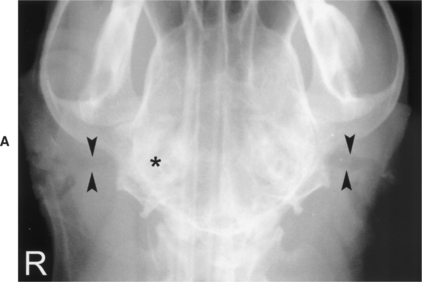

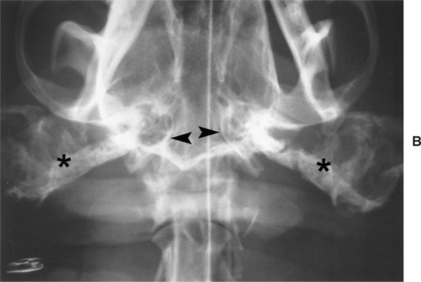

Figure 4-5 A, VD radiograph of a 4-year-old Doberman diagnosed with chronic bilateral ear infections. Both external acoustic canals (arrowheads) are narrowed and somewhat tortuous. The right canal is smaller and less defined than the left. There is an increased opacity associated with the right tympanic bulla and petrosal portion of the temporal bone (asterisk). Compare the canals with the normal external acoustic canals depicted in Figure 4-3, C. B, VD radiograph of a 2-year-old Bulldog diagnosed with chronic bilateral otitis. Radiographs were taken prior to a total ear canal ablation. There is exuberant bilateral dystrophic calcification of the external acoustic canals (asterisks). The visible walls of the tympanic bullae (arrowheads) appear normal.

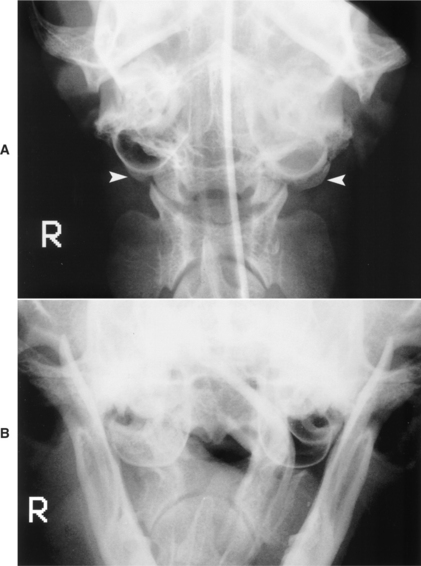

Diseases affecting the middle ear, such as otitis media, neoplasia, and craniomandibular osteopathy, as well as polyps can be evaluated with a bullae series. Radiographic findings are nonspecific; therefore the list of differential diagnoses should be generated in light of the clinical history and not radiographic findings alone.

Common findings in otitis media include thickening of the wall of the bullae, increased soft tissue opacity within the bullae, and increased size of the bullae (Figure 4-6). In the large majority of cases it is not possible to differentiate a fluid-filled bulla from one with a thickened wall. If the process is chronic, the increased opacity is likely the result of both thickening and fluid accumulation. Rare mineral concretions within the bullae, also known as middle ear otoliths, have been reported in four dogs.3,4 Middle-ear otolithiasis may be associated with nonactive or active cases of otitis media. If the otitis media is secondary to otitis externa, narrowing and mineralization of the external acoustic canal can also be seen.

Common findings associated with neoplasia affecting the middle ear include soft-tissue swelling, which may or may not obliterate the external acoustic canal; lysis of the wall of the bullae; and increased opacity of the bullae without lysis (Figure 4-7). Less commonly, ill-defined periosteal reactions arising from the bullae and surrounding bones can be seen. Neoplasia of ceruminous glands, squamous cell carcinomas, and anaplastic carcinomas have been diagnosed among others.5,6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree