Chapter 22 Pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lung parenchyma.1,2 It occurs chiefly in response to inhalation of infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, parasites) either as a primary disorder or secondary to a predisposing disturbance in the lungs. Less common causes of pneumonia include idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia, secondary to inhaled allergens or a hematogenous infection, and endogenous lipid infiltration.1 Pneumonia that occurs as a result of inhalation of foreign substances or materials is described in Chapter 23, Aspiration Pneumonitis and Pneumonia. The focus of this chapter is infectious pneumonia.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Initial Evaluation

Critically ill animals with pneumonia require rapid identification and treatment. A soft cough, mild dyspnea, and nonspecific signs of lethargy and inappetence may be noted as the earliest manifestations in some dogs and cats. However, many patients with pneumonia show no respiratory signs (e.g., 36% of cats).3 The spectrum of clinical signs ranges from none (the diagnosis is made incidentally on thoracic radiographs) to life-threatening dyspnea and impending cardiorespiratory arrest. Therefore pneumonia may be suspected at one of several points in the evolution of a case: when clinical signs are noted, when predisposing causes are identified, or when characteristic findings are apparent on thoracic radiographs.

History

Elements of a patient’s history that should raise the clinician’s index of suspicion for pneumonia are numerous. Broadly, historical clues include respiratory signs (cough, increased respiratory effort, purulent nasal discharge), systemic signs including lethargy and inappetence, and signs associated with predisposing or underlying causes (Table 22-1). Approximately 36% to 57% of dogs with pneumonia are found to have a concurrent predisposing disorder.4,5 Geographic location and travel history may reveal important details to consider in cases suspected of having fungal or parasitic disease.

Table 22-1 Factors Predisposing to or Associated With Pneumonia in Dogs and Cats

| Factor | Comment |

|---|---|

| Impaired patient mobility | |

| Unconsciousness (natural, or via general anesthesia)* | Attenuation, loss of reflexes (gag, cough) |

| Mechanical ventilation | Natural defense mechanisms of the upper airway bypassed by intubation and mechanical ventilation; normal movement and coughing preventedRegurgitation or aspiration of oropharyngeal bacteria may contribute |

| Weakness, paresis, paralysis* | — |

| Upper airway disorders | |

| Laryngeal mass or foreign body* | Successful laryngeal examination possible using only a bright light source (Finnoff transilluminator) and without sedation in patients with laryngeal disorders, especially laryngeal paralysis |

| Laryngeal paralysis* | |

| Laryngeal or pharyngeal surgery* | Aspiration pneumonia (without overt clinical signs)—a common postoperative complication in animals with laryngeal paralysis (see Chapter 23, Aspiration Pneumonitis and Pneumonia) |

| Regurgitation syndromes | |

| Esophageal motility disorder* | Dynamic esophagram (barium swallow) required for diagnosisImportant if other tests do not identify an underlying cause for pneumonia |

| Esophageal obstruction* | Foreign body sometimes visible on thoracic radiographsCaution necessary with barium swallow procedures (barium aspiration risk) |

| Megaesophagus* | Often identifiable concurrently on thoracic radiographs |

| Other factors | |

| Bronchoesophageal fistula | Usually acquired via trauma (e.g., perforating esophageal foreign body) |

| Cleft palate | Congenital abnormality that may cause ingesta to enter nasal cavity with subsequent aspiration |

| Crowded or unclean housing | Persistence and concentration of infectious organisms in environment contributors to risk |

| Forceful bottle feeding* | Aspiration possible when care provider squeezes the nursing bottle during suckling, or if hole in nipple is too large |

| Gastric intubation* | — |

| Immune compromise | Specific conditions: anticancer or immunosuppressive chemotherapy; concurrent illness including feline leukemia, feline infectious peritonitis, diabetes mellitus, or hyperadrenocorticism; primary ciliary dyskinesia; immunoglobulin or leukocyte defects or deficiencies |

| Inadequate vaccination | Viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection with secondary opportunistic bacterial pneumonia |

| Induced vomiting* | — |

| Seizures* | Must differentiate pneumonia radiographically from noncardiogenic pulmonary edema |

| Tracheostomy* | — |

Physical Examination

Physical abnormalities in patients with pneumonia often are nonspecific beyond respiratory signs.1,5 Demeanor may be normal, with some patients showing a bright and alert disposition despite having pneumonia, or abnormal, with lethargy and depression predominating. Inappetence, weight loss, and signs attributable to an underlying disorder are common. Respiratory signs are rarely sensitive or specific. For example, dyspnea occurs with moderate or severe pneumonia, but is absent in mild cases. The cough of a patient with pneumonia may be moist or dry, and tracheal pressure may elicit a cough in some pneumonia patients and not in others. Most dogs with pneumonia (>90%) do have abnormally loud breath sounds, crackles, or wheezes on pulmonary auscultation6; however, these findings are nonspecific and do not allow differentiation from other causes of dyspnea (pulmonary edema, pulmonary hemorrhage). In contrast to dogs (47%),6 cats with infectious pneumonia rarely cough (8%).3 Mucopurulent nasal discharge may or may not be present in either species. Fever is a highly inconsistent finding in both species, and pneumonia can be neither confirmed nor ruled out on the basis of body temperature. Animals with fungal, viral, parasitic, or protozoal pneumonia may have multisystem involvement (e.g., bone, intestinal tract, lymph nodes). Overall, pneumonia is suspected in an animal when one or more compatible signs are noted in the history and physical examination, especially in a patient with a predisposing condition (see Table 22-1).

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

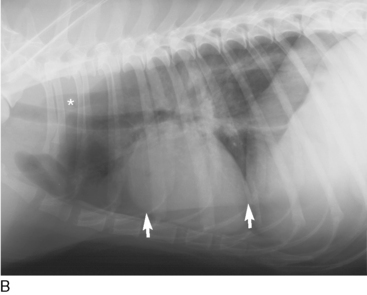

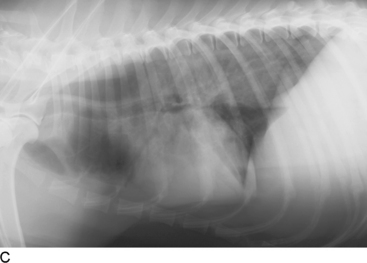

Evaluation of patients suspected of having pneumonia is centered on diagnostic imaging and sampling respiratory secretions. Thoracic radiography remains the routine imaging test of choice. The characteristic finding is alveolar opacification. Air bronchograms, silhouetting of lung(s) with the heart, and consolidation, with or without interstitial patterns, are typically present with an asymmetric distribution (Figure 22-1). The alveolar pattern of pneumonia often is visualized more clearly in one radiographic view than in another. For example, a left lateral thoracic radiograph will allow optimal visualization of the right lung fields. Therefore, three-view thoracic radiography (a dorsoventral or ventrodorsal projection and both lateral projections) is recommended in all pneumonia suspects, in order to minimize false-negative results and underdiagnosis. Computed tomography may also be beneficial in animals with complicated pulmonary disease or with those suspected of having foreign body–associated pneumonia, to assist in the approach to exploratory thoracostomy or lung biopsy.

Figure 22-1 A, Thoracic radiograph of a dog with pneumonia, dorsoventral projection. Alveolar infiltrates are seen most clearly in the central region of the right lung: the right middle lung lobe and adjacent regions of the right caudal lung lobe. B, Thoracic radiograph of the same dog, right lateral recumbent projection. The infiltrated lung is in the dependent region and not clearly visible; pneumonia could be falsely ruled out if this projection was the only one taken of this dog. Some gas is present in the esophagus (asterisk) and a prominent skin fold (arrows) should not be mistaken for a pleural fissure line. C, Thoracic radiograph of the same dog, left lateral recumbent projection. The infiltrates within the right middle lung lobe are clearly seen (note prominent air bronchograms), as is marked gaseous and soft tissue and fluid distention of the esophagus. Diagnosis: evidence of pneumonia and concurrent megaesophagus, suggesting aspiration as the inciting mechanism.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree