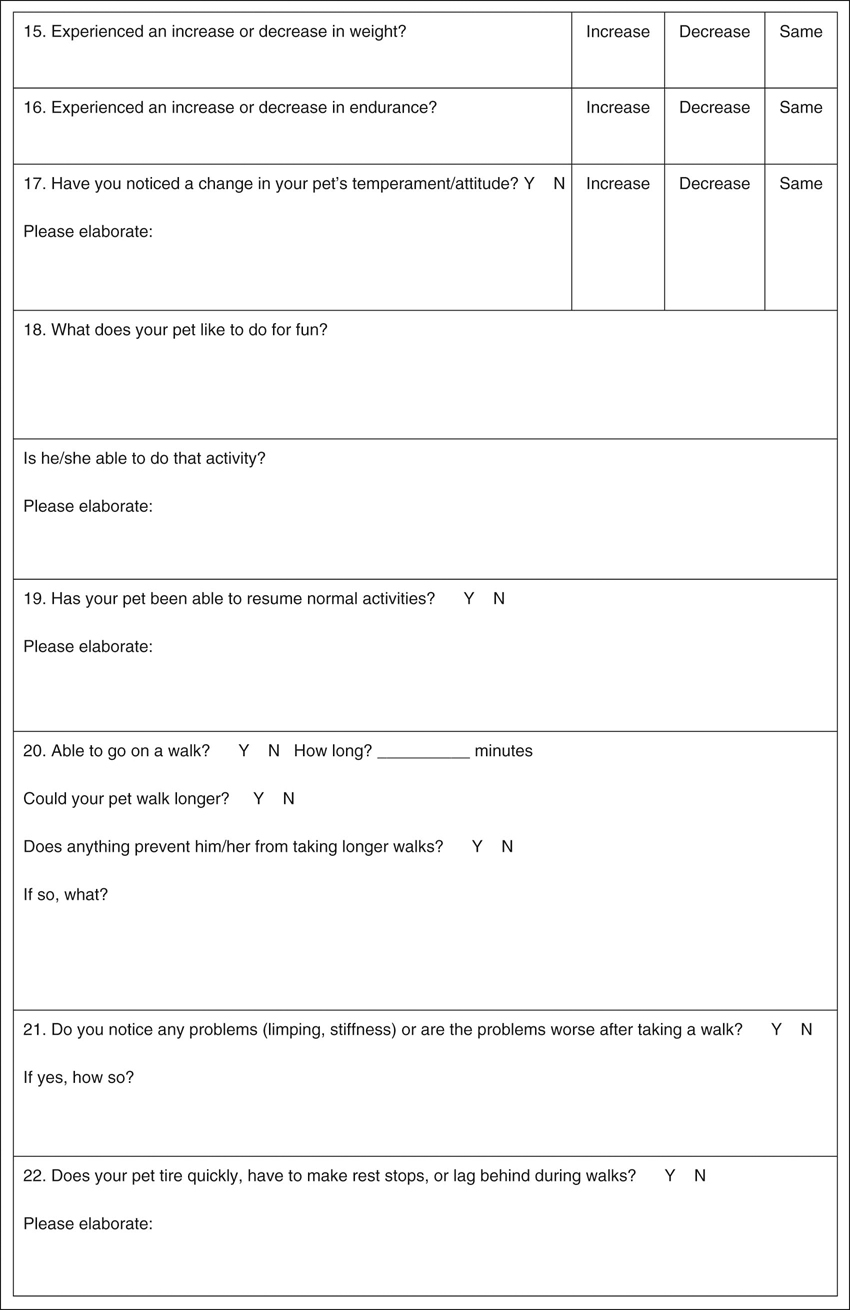

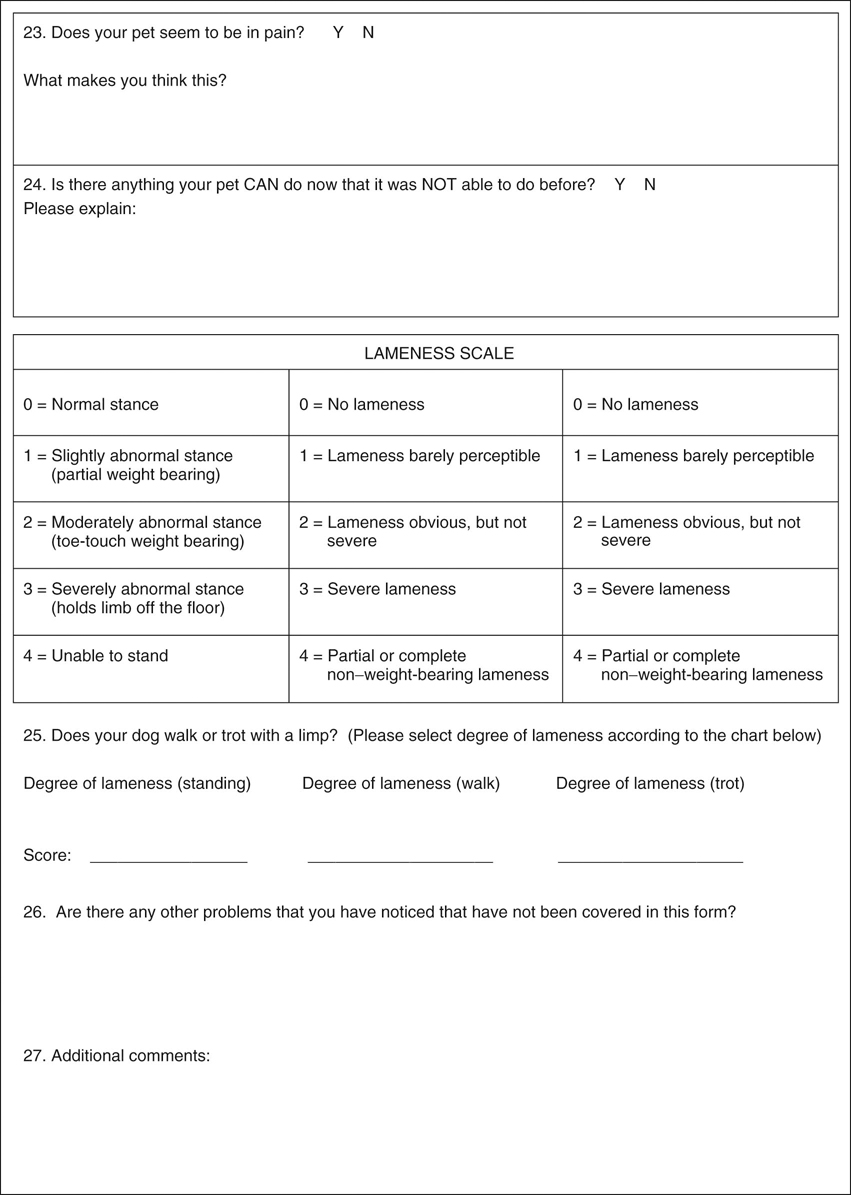

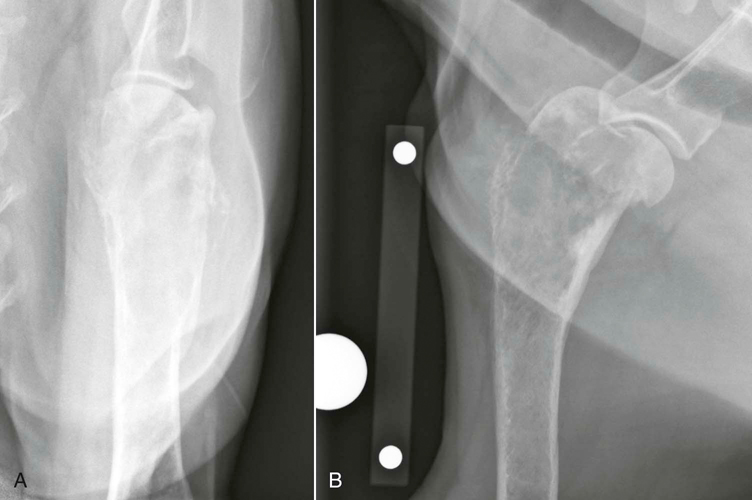

Denis J. Marcellin-Little, David Levine and Darryl L. Millis The term geriatric relates to elderly people. The World Health Organization defines middle-age as being 45 to 59 years, elderly as being 60 to 74 years, and aged as being 75 years and older.1 No such groupings have been proposed in dogs, although Table 35-1 describes the ages at which dogs are considered “geriatric” and are likely to develop diseases associated with aging.2 Aging itself is not a disease. Multiple factors, including genetics, environment, and nutrition, play a role in the aging process. For example smaller dog breeds live longer than larger breeds, and mixed-breed dogs have a longer life expectancy than purebred dogs. Obese animals have a shorter life span than non-obese animals.3 Dogs that are neutered live longer than those that are not neutered. Pets that live inside live longer than those that are housed outside.4 Table 35-1 Typical Ages at Which Various-Sized Dogs May Be Considered Geriatric There are multiple changes that occur as a result of the aging process in dogs, as outlined in Box 35-1. Most of these conditions are chronic (endocrinopathies, hepatic disease, renal disease, cardiac insufficiency) and require lifelong treatment and sustained owner compliance. It is important for the therapist to understand the effects these diseases have on function and activities of daily living. For example, hypothyroidism may cause lethargy and easily could be mistaken for arthritis and inactivity. It is important for the owner to make regular appointments with their veterinarian for patient monitoring and modification of the treatment plan, as necessary.4 The changes associated with aging are progressive and are hastened by stress, the environment, genetic factors, malnutrition, and lack of activity. The effects of aging have been documented in human beings,5 and similar effects are seen in dogs. Quite often, owners of geriatric dogs attribute specific changes in behavior and lifestyle, such as a decreased appetite, changes in sleeping patterns, or decreased activity, to their pet becoming arthritic or being old. Although a component of these changes could be the aging process, the presence of concurrent neurologic, musculoskeletal, or metabolic diseases should also be considered. In geriatric dogs, the diagnosis and treatment of systemic diseases are necessary for the success of a rehabilitation program aimed at managing a disorder such as osteoarthritis (OA). The increased likelihood of multiple conditions being present in a geriatric dog warrants a thorough medical evaluation before a rehabilitation program is designed. A complete medical history, including previous medical diagnoses and treatments, may help determine the origin of the patient’s primary problem and identify any previous or concurrent diseases that may affect the success of rehabilitation. In conjunction with the history, performing a thorough physical examination and obtaining hematologic information may confirm the presence of concurrent diseases. Multiple disease processes in older animals, such as those listed in Table 35-2, can cause nonspecific signs that mimic or exacerbate the signs of OA or aging. These signs include weakness, lethargy, and exercise intolerance. Treatment of concomitant diseases before the implementation of a rehabilitation program allows the patient to be in the best condition to appropriately respond to rehabilitation and allows the clinician to provide the most accurate prognosis. If the concurrent disease requires long-term treatment, frequent adjustments of the medical therapy and the rehabilitation program may be required to reach the goals of each treatment. For example some of the most common systemic diseases in older animals are endocrine disorders and neoplasia.6 Those conditions that have associated neurologic and musculoskeletal involvement, such as hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, osteosarcoma, and insulinoma interfere with the implementation of a successful rehabilitation program and accurate assessment of the patient’s progression during the program. Understanding the pathophysiologic mechanisms is important not only for the successful treatment of the concurrent disease but also for the development of a rehabilitation plan tailored to the needs and weaknesses of the individual patient. Communication between the veterinarian, therapist, and owner is important and facilitates the assessment of the response to the rehabilitation program and the management of concurrent diseases. Table 35-2 Common Medical Conditions Present in Geriatric Dogs, Organized by Organ Systems The list of common geriatric diseases is outlined in Box 35-2. The most important systems related to rehabilitation care are the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Muscle mass and bone mass decrease with aging. Muscle function is diminished as a result of muscle fiber atrophy, loss of elasticity, and reduced oxygen transport to muscles. Cartilage tends to deteriorate as a result of altered biomechanical integrity and loss of tensile strength. The most common problem of the musculoskeletal system in geriatric dogs is OA. Obesity compounds the effects of arthritis (Figure 35-1).4 Decreased intestinal absorption of calcium and decreased activity level may result in decreased bone mineral content. Osteoporosis, or reduction in the quantity of bone, is rarely clinically significant in aging dogs. The primary importance of senile osteoporosis is its influence on fracture healing. Callus formation is slower in older animals, and fractures require additional healing time. This increases the likelihood of delayed or malunion fractures, muscle atrophy, and disuse osteoporosis. Neoplasia involving the musculoskeletal system, although less common in some breeds of dogs, also must be considered. Primary bone tumors are the most common and include osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and hemangiosarcoma (Figure 35-2).4 Several conditions affecting the nervous system also affect aging dogs. In addition to intervertebral disk disease, degenerative conditions such as degenerative myelopathy and spinal neoplasia may occur in older dogs (Figure 35-3). Cognitive dysfunction is a common issue in older dogs. These dogs may exhibit signs such as loss of house training, disturbances in sleep and wake cycles, inattention to food or their environment, and inability to recognize familiar people and places. Short-term memory is affected by changes in interneurons that cause a prolonged effect to a stimulus and increased response time to the external environment.4 Cognitive dysfunction also may affect the patient’s ability to participate in some activities of a rehabilitation program. A geriatric screening program should be implemented as part of a general wellness program for animals 8 years and older. This allows the veterinarian to target geriatric-related health problems, detect early geriatric disease to implement effective medical care, and offer preventive health care measures. Client education plays a large role in this process. Owners should be instructed on the normal process of aging, nutrition, appropriate exercise, and bereavement counseling, when indicated. A questionnaire is helpful to provide a baseline for function and may be used to reassess the animal’s quality of life over time (Figure 35-4). The normal process of aging includes changes in muscle physiology, hair coat and skin, cognitive function, hearing, and vision. These changes should be assessed, recorded, and addressed as part of the overall treatment program. The initial amount of exercise in the aging dog should be easily tolerated, with increasing amounts added as the rehabilitation program progresses. Low-impact exercise, such as frequent short leash walks and swimming should occur regularly, possibly on a daily basis. Owners should be aware of changes in water or food consumption, rapid weight changes, abnormal urination or defecation, changes in activity level, vomiting, or diarrhea (Figure 35-5). When appropriate, clinicians should advise owners during the final weeks of the animal’s life and after their death.1 Because aging dogs may have a fragile physiologic balance, pain management of geriatric dogs should rely as much as possible on therapeutic options with minimal physiologic impact. For example, geriatric people are more sensitive to the gastrointestinal side effects of antiinflammatory medications than younger people.7 The same most likely applies to dogs.8 Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should therefore be used with caution in geriatric dogs. The pain management options with minimal physiologic risks include but are not limited to low-impact exercises, massage, and therapeutic heat and cold. Analgesic medications that may be helpful include amantadine, gabapentin, and tramadol. In patients with severe pain, such as may be present with neoplasia, opioid drugs may be prescribed, or transcutaneous fentanyl patches may be applied for sustained delivery of medication. Although these patches may be helpful in the short term, they are rarely used over extended periods of time because of the cost and other factors involved with prolonged treatment.

Physical Rehabilitation for Geriatric and Arthritic Patients

Aging in Dogs

Weight

Age (Mean ± Standard Deviation)

Small dogs

0-20 lb

11.48 ± 1.86

Medium dogs

21-50 lb

10.19 ± 1.56

Large dogs

51-90 lb

8.85 ± 1.38

Giant dogs

>90 lb

7.46 ± 1.27

Medical Considerations

Organ System

Condition

Cardiovascular

Cardiomyopathy

Endocardiosis

Arrhythmias

Heartworm disease

Pericardial disease

Systemic hypertension

Endocarditis

Upper respiratory tract

Laryngeal paralysis

Brachycephalic respiratory syndrome

Laryngeal and pharyngeal neoplasia

Bronchomalacia

Collapsing trachea

Lower respiratory tract

Pneumonia

Neoplasia (primary or metastatic)

Pleural effusion

Pulmonary edema

Bronchitis

Pneumothorax

Gastrointestinal

Malabsorptive disease (inflammatory bowel disease)

Protein-losing enteropathy

Neoplasia (adenocarcinoma, lymphoma)

Hepatobiliary

Hepatic parenchymal disease (chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, neoplasia, toxic hepatitis)

Biliary tract abnormalities (pancreatitis, bile duct neoplasia, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis)

Endocrine

Hyperparathyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Hyperadrenocorticism

Hypoadrenocorticism

Thyroid neoplasia

Insulinoma

Diabetes mellitus

Pheochromocytoma

Thymoma

Hypoparathyroidism

Urinary tract

Renal failure

Urinary tract infection

Urinary incontinence

Hematologic and immunologic

Anemia (regenerative or nonregenerative)

Neoplasia (lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma, leukemia)

Hemostatic disorders

Immune-mediated polyarthritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Neurologic

Intervertebral disk disease

Cervical spondylomyelopthy

Lumbosacral instability

Degenerative Myelopathy

Neoplasia

Musculoskeletal

Osteoarthritis

Neoplasia

Common Musculoskeletal and Neurologic Considerations

Figure 35-1 The most common problem of the musculoskeletal system in aged dogs is osteoarthritis. Dogs may have difficulty arising, and obesity compounds the effects of arthritis.

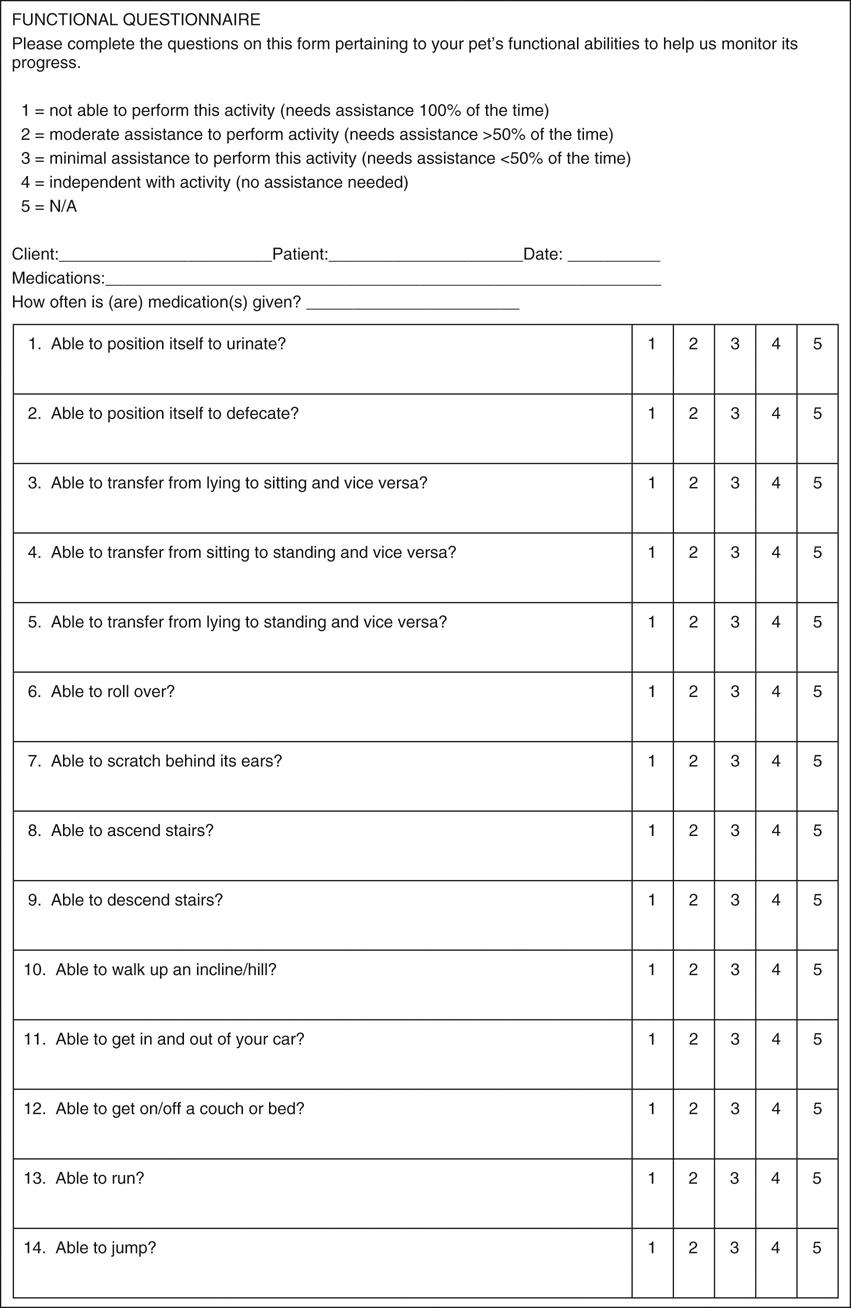

Figure 35-2 This 8-year-old spayed female rottweiler has an osteosarcoma in the proximal portion of the humerus visible on caudocranial (A) and mediolateral (B) radiographic projections. Classic clinical signs of osteosarcoma include lameness, lethargy, and decreased appetite.

Maintaining Quality of Life

Pain Management in the Geriatric Dog

Physical Rehabilitation for Geriatric and Arthritic Patients

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree