Physical Examination and Conformation

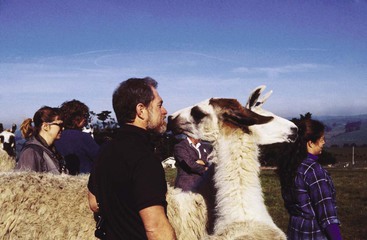

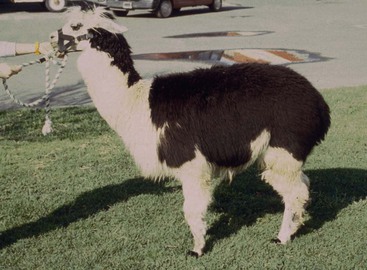

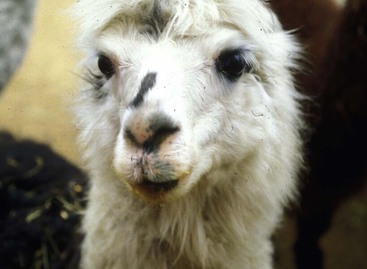

From the outset, the reader should be aware of the marked similarities between the two domestic members of the South American camelids (SACs), the llamas and the alpacas. As such, in most cases, procedures of physical examination are applicable to both members of the species. The most striking differences between the two are body size and weight, fineness of wool, body conformation, and temperament. Alpacas are expected to be predictably smaller, have fine wool, have a normal conformation characterized by marked rounding of the rump (Figure 30-1), and generally have a herd temperament, which makes it somewhat more excitable as an isolated individual. Except for unusual animals, a clinical examination will necessitate the use of a restraining chute (Figure 30-2) or at least some manual restraint and occasionally chemical restraint. Their reluctance to cooperate with minimal restraint (e.g., halter) is traced to their social or herd behavior, which includes extreme dominant and subordinate relationships. These relationships are established by body language and sparring, the latter including the practice of either playful or serious biting at the limbs, ears, and even gonads. As such, camelids tend to protect their anatomically sensitive areas, and this makes it essential for an examiner to acknowledge and, as such, work around this tendency. Most animals will be presented individually for clinical examination. These may be on their own turf or off their turf (e.g., at a clinic). In either case, a degree of apprehension with regard to the examination is to be expected in the animal but is likely to be more exaggerated in a new setting. From time to time, herd evaluation may be necessary. On such occasions, it is important to be aware that camelids are extremely visual and innately curious but cautious animals. As such, a normal herd will have animals that vary considerably in their responses to the presence of the examiner. Once “the vet” has been recognized, some may retreat and others may show their usual curiosity. Llamas that approach the examiner and seem very “friendly” are not usual and, in most cases, will be found to exhibit abnormal behavior toward humans (Figure 30-3). The clinical examination of llamas or alpacas should be conducted in an organized, repetitive fashion, undoubtedly quite similar to that performed on cattle and horses.

Observation and Inspection of the Patient

Unless extremely ill, most camelids are alert and extremely aware of the presence of the examiner. Whether restrained or not, many will demonstrate apprehension to your attention by voluntarily producing a near-ectropion of the lower lid that results in a “worry wrinkle.” This is accompanied by a tightening of the lips (Figure 30-4). At this stage of anxiety, the examiner should not be surprised to observe moist footprints from the animal sweating on the examining surface. Animals that are truly defensive will posture themselves to face the examiner, lay their ears back, and raise their heads. Unless the animal is aggressive to approach, the usual way of approaching a defensive animal is to avoid eye contact and casually attempt to make body contact by touching the animal’s body with the back of the hand, encircling the neck with the right hand from the animal’s left side, moving forward to place the right hip against the animal’s left shoulder, and gently placing a halter into position. Under field or farm conditions, this would, presumably, be accomplished by the owner.

Camelid owners and experienced veterinarians agree that patient stoicism is a factor to acknowledge in assessment by inspection. As such, it appears that even neonates may present an impression of well-being in spite of serious health alterations. Presumably, close physical inspection or indicated subsequent laboratory pursuits will aid in pinpointing a diagnosis.

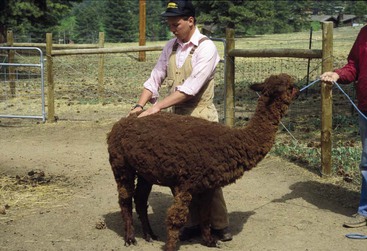

Whether the animal is free in a stall or presented with halter and lead, an assessment of conformation should be done. Guidelines on determining normal conformation are quite similar to those for the horse with regard to limbs, with the exception that most camelids will normally toe out somewhat with the forelimbs. The highest incidence of limb conformation abnormality may be carpus valgus; however, cow hock and sickle hock conditions are observed. Abundant leg wool in alpacas and some llamas make evaluation of leg conformation somewhat difficult (Figure 30-5). Repeated positioning of the animals in the standing position may be essential to make a final judgment on limb conformation, as these animals have the tendency to be somewhat erratic in limb placement. Alpacas generally tend to appear somewhat sickle-hocked and thus “camped under” because of their normal rounded rump (Figure 30-6). Evaluation of the normal walking gait reveals a near pace, with only the slightest delay of the same side forelimb touching the ground after the hindlimb. Depending on the width of the chest, the tracking may be wide or narrow; however, the utility of llama packing favors a narrow track. The observed gaits of a free camelid include the walk, the pace, the gallop, and “pronking” (springing into the air with all four feet lifted off the ground). Generally, during a soundness or prepurchase examination, the animal is led at a walk, and only when assessing cardiac and respiratory functions would more vigorous exercise be indicated.

Soundness

Close Physical Examination

Peripheral Pulse

In practical terms, the location that is reliable for ascertaining the peripheral pulse in camelids is the medial saphenous artery located on the inside of the rear leg at the level of mid-femur (Figure 30-7). If the individual animal is restrained in a chute, an evaluation is best accomplished, for example, by first making contact with the fiberless area of the left abdomen and gradually moving the left hand to the inside of the left rear leg, where the artery will readily be detected. Contact with the lower limb should be avoided, as this will usually create uneasiness. Pulse rate will vary with the degree of excitability from the procedure but should be in the range of 60 to 90 beats per minute (beats/min).

Respiratory Rate or Character

The resting respiratory rate may be best determined through observation of nostril flaring; however, during normal clinical examination, it can be determined by stethoscope auscultation over the trachea in the lower neck region. Normal rates tend to have a wide range (10–30/min), with combined thoracic and abdominal effort. Exaggerated abdominal involvement would be deemed abnormal, suggesting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Body Condition Score

A subjective assessment of body condition is important for the current physical examination as well as for subsequent nutritional considerations. A scale of 1 (thin) to 9 (fat), with 5 being ideal, is utilized. Principal locations for assessment include the midback (T8-L2) region as well as the fiberless area of the chest behind the point of the elbow. Palpation only over the dorsal pelvis tends to suggest poor body condition in all camelids as all will feel boney (Figure 30-8). In addition, particularly in animals deemed overconditioned, assessment of the brisket and the perineal region has proven to be of value.

Visible Mucous Membranes

As with most species, available sites for assessment of mucous membranes are limited to the oral mucosa and conjunctivae (Figure 30-9) except in female camelids, in which the vaginal mucosa is utilized. Many camelids have variable degrees of oral pigmentation, making evaluation a bit challenging; however, pink coloration indicates normalcy. Attempts to assess the capillary refill time are first made from the orolabial mucosa, but the vaginal mucosa is also of value.

Assessment of Skin

Considering the extensive wool covering on most of the body of the camelid, true evaluation of the skin requires a hands-on approach. Skin on the head and ears is normally covered with fine hair, but many animals may have rubbed the hair from the dorsum of their nose (dorsal nasal alopecia) and ears (Figures 30-10 and 30-11) in response to summertime bug bites. The areas of the perineum and the brisket as well as the underbelly and a small area behind the point of the elbow can be evaluated without parting the wool. Normal camelid skin is soft but not readily pliable, which makes tenting for assessment of hydration very difficult. Parting the wool over the dorsum generally yields a variable amount of debris trapped in the wool and makes assessment for ectoparasitic infestation and dryness as well as dandruff somewhat more challenging (Figure 30-12). Lice tend to be located along the dorsum, making this the main area for inspection. In contrast, mange tends to be present at least initially over the fiberless areas of the perineum, brisket, and lower limbs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree