Chapter 74 Pheochromocytoma

DIAGNOSIS

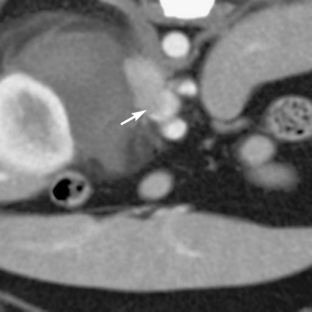

Advanced imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are very helpful for determining the size of the tumor and the extent of tumor invasion, although these require general anesthesia in the veterinary patient. Nonionic, low-osmolar contrast media is recommended for CT studies to minimize adverse reactions.18 Gadolinium contrast for MRI studies is not contraindicated in patients with a suspected pheochromocytoma.19 CT findings in dogs with pheochromocytoma show a lobulated, irregularly shaped mass associated with the adrenal gland. Areas of decreased intensity are interspersed with highly vascular areas with increased intensity (Figures 74-1 and 74-2).18 MRI may be used to differentiate between histologic types of adrenal tumors.2 Scintigraphy using 123iodinemetaiodobenzylguanidine (an NE analog) or 99mtechnetium-methylene diphosphonate has been used in the dog to identify a pheochromocytoma.20,21 One group used p-[18F]fluorobenzylguanidine to identify tumors in dogs using positron emission tomography.22 These techniques are useful for identifying metastatic tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree