Chapter 133 Peritonitis

INTRODUCTION

More commonly, secondary peritonitis can be identified as a septic process, with the most frequent source of infection being the GI tract. Leakage of GI contents may occur through stomach and intestinal walls that have been compromised by ulceration, foreign body obstruction, neoplasia, trauma, ischemic damage, or dehiscence of a previous surgical incision. Spontaneous gastroduodenal perforation may be associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug administration but may also be seen with corticosteroid administration, neoplastic and nonneoplastic GI infiltrative disease, gastrinoma, and hepatic disease.1,2 GI linear foreign bodies in dogs have been reported to lead to the development of peritonitis in 41% of cases, higher than that previously reported for cats.3 Dehiscence occurs in 7% to 16% of postoperative patients requiring intestinal enterotomy or anastomosis, with mortality rates of 75% to 85% in this population. One study identified dogs as being at high risk for leakage following intestinal anastomosis if they had two or more of the following conditions: preoperative peritonitis, intestinal foreign body, and a serum albumin concentration of 2.5 g/dl or less.4 Other causes of septic peritonitis can be found in Box 133-1.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Clinical signs of dogs and cats with peritonitis vary in both type and intensity and may reflect the underlying disease process. Peritoneal effusion is a consistent finding but may be difficult to appreciate on physical examination if a small volume of fluid is present, and may even be difficult to detect sonographically in animals exhibiting dehydration. Abdominal pain may be appreciated on palpation, with a small number of dogs exhibiting the “prayer position” in an attempt to relieve abdominal discomfort. In a retrospective study focusing on cats with septic peritonitis, only 62% exhibited pain on palpation of the abdomen.5 Most animals with septic peritonitis are systemically ill and exhibit nonspecific clinical signs such as anorexia, vomiting, mental depression, and lethargy. It should be noted that animals with uroperitoneum may continue to urinate with a concurrent leakage into the peritoneal cavity. These patients may arrive in progressive states of hypovolemic and cardiovascular shock, with either injected or pale mucous membranes, prolonged capillary refill time, tachycardia with weak pulses, and with either hyperthermia or hypothermia reflecting poor peripheral perfusion. A significant number of cats (16%) with septic peritonitis exhibited bradycardia5 (see Chapter 106, Sepsis).

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

A diagnostic peritoneal lavage should be performed when peritonitis is suspected despite the absence of detectable effusion or when a minimal volume of effusion makes it difficult to obtain a sample. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage ideally is performed using a peritoneal dialysis catheter but can also be performed using an over-the-needle, large-bore (14 to 16 gauge) catheter. The technique is performed by infusion of 22 ml/kg of a warmed, sterile isotonic saline solution through the catheter inserted in an aseptically prepared site just caudal to the umbilicus and retrieval of a sample for analysis and culture and sensitivity. It is important to remember that the lavage solution will dilute the sample and therefore may alter the analysis. A repeated diagnostic peritoneal lavage may increase accuracy of the technique when results of the first procedure are equivocal (see Chapter 156, Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage).

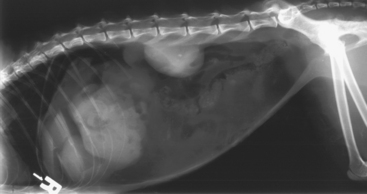

Plain radiographs may reveal a focal or generalized loss of detail that is otherwise known as the ground glass appearance. A pneumoperitoneum (Figure 133-1) suggests perforation of a hollow viscous organ, penetrating trauma (including recent abdominal surgery) or, less commonly, the presence of gas-producing anaerobic bacteria. Intestinal tract obstruction or bowel plication should be ruled out. Prostatomegaly in male dogs and evidence of uterine distention in female dogs should be noted. Thoracic radiographs should be performed to rule out concurrent illness (infectious, neoplastic, or traumatic). The presence of bicavitary effusions increased the mortality rate of patients 3.3-fold compared with that of patients with peritoneal effusions alone.11 Ultrasonography may be useful for defining the underlying etiology of peritonitis, in addition to its use in localizing and aiding retrieval of peritoneal effusion. In the case of a confirmed uroabdomen, preoperative contrast radiography (excretory urography or cystourethrography) is recommended to localize the site of urine leakage and aid in surgical planning. It should be noted that all patients should be hemodynamically and medically stabilized before diagnostic imaging is carried out.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree