CHAPTER 108 Pelvic Fractures

Historically, pelvic fractures have been considered to be an infrequent cause of lameness in horses, accounting for less than 5% of all lameness. It is well documented that young horses are predisposed to pelvic fractures: in one study, 60% of the horses were less than 2 years of age, and 76% were less than 4. Although it has also been reported that young females are more likely to sustain a fracture than young males, findings from a recent retrospective study of young horses with pelvic fractures indicated that male and female horses were equally affected. Most recently, pelvic stress fractures have been found to be a common cause of lameness in skeletally immature Thoroughbred racehorses. Although the etiologies of the two types of fractures are different, the practitioner still faces the challenges of diagnosing and predicting a prognosis for these horses.

ANATOMY

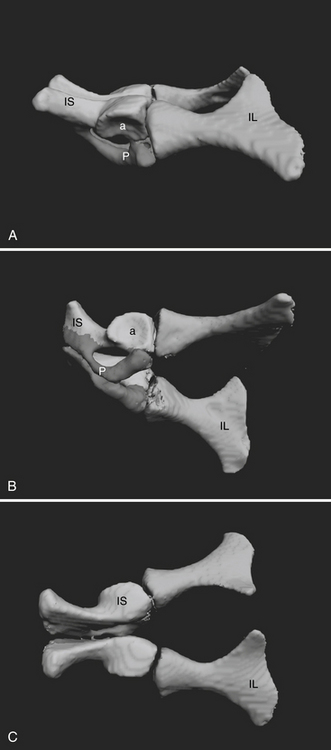

The equine pelvis is divided into two symmetric halves. Each half comprises three bones that are formed from separate ossification sites in a single cartilage plate. Because the bones form from this single cartilage plate, it is only for ease of discussion that the bones are described as separate units. The three bones meet at the acetabulum: the ilium cranially, the ischium caudally, and the pubis medially. The acetabulum helps form one of the three joints of the pelvis, the hip joint (referred to as the coxofemoral joint). The coxofemoral joint is by far the most mobile of the three joints. The two halves of the pelvis meet ventrally at the pubic symphysis, which is a joint that becomes mineralized with age and forms a bony union in most horses. Dorsally the two pelvic halves meet the sacrum and form two firm, but not rigid, synovial joints, the sacroiliac joints. The ilium has a large wing of bone that extends from the tuber sacrale on midline and continues laterally to the tuber coxae. The large wing of bone narrows into the shaft and extends caudally to form the cranial portion of the acetabulum. The ischium forms the caudal portion of the acetabulum and extends caudally, ending at the tuber ischii. The pubis joins the two acetabula, connecting the two pelvic halves, and forms the floor of the pelvis (Figure 108-1). The arrangement of the pelvic girdle supplies the fulcrum needed for the pelvic muscles to provide propulsive forces for the hindquarters. A good understanding of pelvic anatomy aids the clinician in diagnosing and treating fractures as well as predicting where fractures may occur as a result of biomechanical forces placed on the bones.