6 Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the factors that contribute to the development of periodontal disease in dogs and cats.

• Define periodontal disease and describe the appearance of the gingival and other supporting tissues when periodontal disease is present.

• Discuss the etiology of periodontal disease and define the terms plaque and calculus.

• Characterize the bacterial colonization present with periodontal disease and explain how the patient’s immune response contributes to damage to periodontal tissues.

• Differentiate between Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 furcation exposure.

• Describe the staging of periodontal disease using the AVDC classification system.

Clients often ask, “Why does my pet have periodontal disease when all the pets I have had in the past had no dental problems?” Many factors determine the reason one patient develops periodontal disease and another does not (Box 6-1). These factors are as follows: age, species, breed, genetics, chewing behavior, diet, grooming habits (which can cause impaction of hair around the tooth and in the gingival sulcus), orthodontic occlusion, health status, home care, frequency of professional dental care, and bacterial flora of the oral cavity.

Periodontal Disease

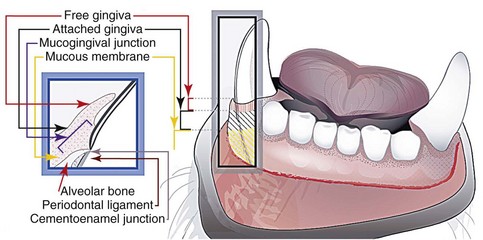

Periodontal disease is an inflammation and infection of the tissues surrounding the tooth, collectively called the periodontium (Figure 6-1). Periodontal disease is characterized by movement of the gingival margin toward the apex (exposing more crown and root) and migration of the attached gingiva with associated loss of the periodontal ligament and bone surrounding the tooth. An older term, pyorrhea, which indicates discharge of pus from the periodontium, is no longer used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree