Chapter 6 Palpation

Palpation of the Forelimb

Foot

The importance of the foot cannot be overemphasized, and it is for this reason that palpation of the forelimb begins here. The feet are included in evaluation of conformation, symmetry, and posture. Detailed static examination (examination at rest) of the foot must always be supplemented with, and correlated to, dynamic observations of foot flight and foot striking patterns. Some horses continually attempt to pick up the limb as the clinician tries to evaluate it with the horse in the standing position; it may be necessary to stroke the contralateral limb to divert attention. A hoof pick, wire brush, hoof knife, shoe-removing equipment, and hoof testers are required (Figure 6-1). The sole and frog and wall of the foot should be cleaned thoroughly. Removal of the shoe at this stage in the examination usually is indicated only if a subsolar abscess is suspected. The veterinarian should take care to preserve the hoof wall, and if it is cracked, protect it with tape.

Foot and hoof balance are assessed by evaluating toe and heel length, hoof capsule conformation, condition and integrity, type of shoe and shoe position relative to the hoof capsule, hoof and pastern angle (axis), medial-to-lateral hoof balance, coronary band conformation, and distal interphalangeal (coffin) joint capsule distention and response to hoof testers. The coronary band should normally be parallel to the ground surface. Deviation from parallel often indicates mediolateral foot imbalance (Figure 6-2). Medial and lateral wall lengths should be assessed while the horse is standing and again with the limb off the ground, with the foot viewed from palmar to dorsal along the solar aspect. The limb is lifted and held in neutral position so the solar surface is perpendicular to the ground. Sheared and underrun heels are commonly associated with lameness (Figure 6-3). Deformation of the hoof capsule is not necessarily a cause of lameness. Many horses with proximal displacement of the medial heel bulb have level foot strikes and otherwise balanced feet. Toe and heel length should be assessed, and the hoof-pastern axis should be determined. The angle of the hoof and pastern should be equal to allow equal loading of all portions of the foot. Forelimb hoof-pastern angles normally range from 48 to 55 degrees, but the absolute angle should not be overemphasized. A straight (parallel) pastern-foot axis is more important. A long-toe, underrun-heel foot conformation causes a broken foot axis and predisposes to palmar foot pain (Figure 6-4).

Careful palpation of the coronary band in the standing and non–weight-bearing position is critical in detecting foot soreness (Figure 6-5). In horses with sore feet, heat and pain often are detected on the sore side of the foot, and a prominent digital pulse usually is present. Effusion of the distal interphalangeal joint capsule accompanies many abnormalities of the foot, from early synovitis to chronic osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint, and those with non-specific foot soreness. The clinician places one finger lateral to, and another medial to, the common digital extensor tendon and gently pushes in on the joint capsule, first laterally and then medially. Ballottement is a useful technique to detect effusion in many synovial structures: with effusion, pushing in on the capsule on one side of the tendon causes elevation of the capsule on the other side. The region of the collateral ligaments of the distal interphalangeal joint should be assessed carefully; focal heat or mild swelling may signify acute injury.

Hoof Tester Examination

“… I feel naked going into a stall without my hoof testers!”5 Hoof testers are essential for evaluation of the foot and are a basic requirement for all lameness examinations. Many types of hoof testers are available (Figure 6-6), but I favor one that is adjustable and can be applied with one hand. A proper evaluation of the foot with hoof testers cannot be done with a pad in place, although useful information can be acquired. The instrument can be applied with or without a shoe in place. The amount of force to apply varies from horse to horse and by region of the hoof, and both false-positive and false-negative responses occur. More force is required when the instrument is used across the heel than when used from sole to quarter. The foot should be held between the clinician’s legs in a relaxed manner. The clinician must be able to feel the horse react to subtle pressure, and if the limb is held too tightly or the horse is not calm during the examination, it is difficult to feel a response. The veterinarian should be careful not to place the outside jaw of the instrument too close to the coronary band, because this may cause a false-positive result. Sole sensitivity is assessed by applying the instrument to three to five sites from heel to toe, on both the medial and lateral aspects of the foot, starting from the angle of the sole (seat of the corn) and proceeding dorsally (Figure 6-7). The responses should be compared. If the sole is readily compressible, pain from bruising, a subsolar abscess, laminitis, fracture of the distal phalanx, and other injuries may be elicited, but in horses with hard horn the response may be negative. To evaluate sensitivity of the frog and underlying deeper structures, the hoof testers should be applied from the lateral aspect of the frog to the medial wall, and from the medial aspect of the frog to the lateral wall, each in the palmar, midportion, and dorsal aspects of the frog (Figure 6-8). Pain over the middle third of the frog has been attributed to navicular disease or navicular syndrome, but the specificity of this association is questionable and there are many false-negative responses. Horses with generalized foot soreness or any other cause of palmar foot pain may respond positively or not at all. Only 19 of 42 horses with navicular region pain responded positively to hoof tester examination in the middle third of the frog, with 50% specificity, 50% positive predictive value, and 48% accuracy.6 Horses with palmar foot pain caused by other conditions were as likely to respond to the test, a finding that obviously prompts questioning of the value of hoof tester examination.6 It is difficult if not impossible to create adequate pressure to cause pain in large breed horses or if the horn is hard. Application of a poultice or soaking the foot may be necessary to soften a hard foot, and reexamination after several days may be rewarding. Hoof tester application to the small feet of foals or ponies may elicit a false-positive response, and hoof tester size or amount of compression may require adjustment.

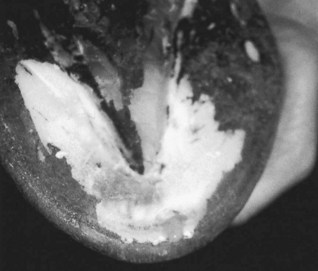

Application of hoof testers across the heel may cause pain in horses with palmar foot pain but is not specific (Figure 6-9). Application of the hoof tester to the area of the sole adjacent to each nail, nail hole, or defect in the sole or white line is useful to detect a subsolar abscess or a close nail (Figure 6-10). Areas of pain can be gently explored with a hoof knife, but unless clearly indicated, the veterinarian should refrain from digging too deeply. The hoof tester can then be used as a hammer to percuss each nail in the shoe and the frog and toe regions.

Wedge Test and Other Forms of Static Manipulation

The wedge test is used most commonly as a dynamic procedure to induce lameness during the movement phase of the examination, but can be used to assess the static response of a horse to dramatic changes in dorsal-to-palmar or medial-to-lateral hoof angles (see Chapter 8, Figure 8-12). A digital extension device, with which the author gauged static painful responses to changes in hoof angle to make shoeing recommendations, was recently described.7

Pastern

The proximal interphalangeal (pastern) joint capsule is assessed by ballottement, although severe effusion must be present for fluid distention to be perceived. Bony swelling associated with this joint, proximal or high ringbone, is a classic cause of lameness yet an unusual clinical finding. Osteoarthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint is a common diagnosis, but one made by a combination of clinical findings, diagnostic analgesia, radiography, and sometimes scintigraphy. The distal extent of the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS), deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), and distal sesamoidean ligaments are palpated. Deep pain associated with the origin and insertion of the distal sesamoidean ligaments is assessed by palpation with the limb in flexion (Figure 6-11). In some horses with lesions of the DDFT within the hoof capsule a positive response to compression of the palmar pastern region is present, but this finding is inconsistent and many false-negative responses occur. The oblique sesamoidean ligaments are difficult to differentiate from the branches of the SDFT, but injury of the SDFT is more common. Distal sesamoidean desmitis or chronic suspensory desmitis may result in subluxation of the proximal interphalangeal joint (Figure 6-12). Swelling should prompt ultrasonographic examination if relevance has been confirmed using diagnostic analgesia. The proximal interphalangeal joint is manipulated in a medial-to-lateral direction to assess pain and collateral ligament integrity and is flexed independently of the fetlock joint. The proximal, dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx is palpated (Figure 6-13). Horses with short, midsagittal fractures or dorsal frontal fractures of the proximal phalanx or proliferation at the attachment of the common digital extensor tendon may show pain. Enthesophyte formation at the common digital extensor tendon attachment, seen most commonly in older ex-racehorses with chronic osteoarthritis of the fetlock joint, results in prominent bony and soft tissue swelling and pain on palpation.

Fetlock

The clinician palpates the joint capsule of the metacarpophalangeal (fetlock) joint with the limb bearing weight, keeping in mind that pain associated with the joint can be present without localizing clinical signs. The dorsal aspect is palpated using ballottement on either side of the common digital extensor tendon. The clinician should determine whether localized heat is present. Osselets is a North American term used to describe early osteoarthritis of the metacarpophalangeal joint in young racehorses, with firm bony and soft tissue swelling on the dorsal, medial aspect of the proximal phalanx, and the distal aspect of the McIII, caused by traumatic capsulitis and early enthesophyte formation. Occasionally in horses with prominent effusion of the metacarpophalangeal joint, a soft tissue swelling can be palpated in the proximal, dorsal aspect of the joint from excessive proliferation of the dorsal synovial pads, called proliferative or villonodular synovitis. The palmar pouch of the metacarpophalangeal joint is palpated dorsal to the SL branches, both medially and laterally. Mild effusion may be present without associated lameness, especially in older performance horses. The PSBs are palpated and assessed for mild swelling and heat, clinical signs of sesamoiditis, or SL avulsion injury. The digital pulse amplitude is reassessed by placing fingers both medially and laterally, abaxial to both PSBs (Figure 6-14).

The limb is elevated to assess range of joint motion and the horse’s response to flexion. Normally the fetlock can be flexed to 90 degrees (the angle between the proximal phalanx and the McIII) or slightly more. A reduction in fetlock flexion range is indicative of chronic fibrosis but is not necessarily a cause for concern. A pronounced response to static flexion is noteworthy, although many horses resent static flexion but do not show a positive response to dynamic flexion (lower limb or fetlock flexion tests; see Chapter 8). Horses with clinically relevant tenosynovitis usually strongly resent fetlock flexion. With the limb in flexion, the clinician palpates the PSBs and the branches of the SL, avoiding compression of the palmar digital nerves.

Metacarpal Region

The medial and lateral palmar digital vein, artery, and nerve, in dorsal-to-palmar orientation, respectively, are located between the SL and DDFT. The accessory ligament (distal or inferior check ligament) of the DDFT (ALDDFT) normally is difficult to palpate and even when enlarged cannot easily be differentiated from the DDFT, but injuries of the ALDDFT are more common. All soft tissue structures should be palpated carefully, using digital compression, with the limb elevated (Figure 6-15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree