Chapter 18 Otitis Interna and Vestibular Disease

Otitis interna, or infection of the inner ear, is a relatively common disorder in the dog. It is usually a result of extension of middle ear infection (see Chapter 14) and results in a characteristic set of clinical signs. These signs reflect the dysfunction of the inner ear organs—namely, the cochlea and vestibular apparatus. Cochlear dysfunction manifests as decreased hearing acuity. This may be difficult to detect in the dog without electrodiagnostic testing, especially if it is unilateral. However, often the astute animal caregiver is able to detect the subtle signs of hearing loss in the animal’s natural environment. This information can be elucidated by careful questioning of the caregiver. The vestibular system is responsible for the detection of acceleration and orientation in respect to the earth’s gravitational field, and it is absolutely essential for an animal to be able to maintain normal balance and posture. It comprises components located in the bony labyrinth of the inner ear and nuclei located in the medulla oblongata.

Components of the Vestibulocochlear System

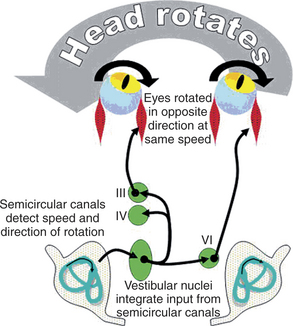

Projections from the vestibular nuclei to the motor nuclei of the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducent (CN VI) nerves control reflex eye movement (Figure 18-1).

Rotation of the head in one direction results in movement of the eyes in the opposite direction at the same speed. This reflex maintains a fixed image on the retina as the head moves. If the head is still moving when the eyes reach the furthest possible excursion in the opposite direction, the area of the pons that controls quick eye movements flicks the eyes quickly in the direction of the head movement, and the drift in the opposite direction begins again. Disease of the vestibular system creates the false perception of rotation, which produces a spontaneous drifting of the eyes in one direction with a quick reset in the opposite direction (spontaneous nystagmus). Projections to a separate area of the brainstem (the emetic center) are responsible for the nausea that may accompany vestibular disease.

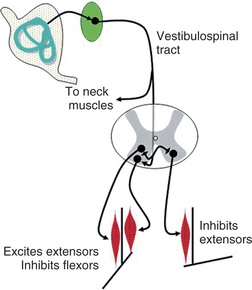

Projections from the vestibular nuclei to the spinal cord maintain balance and support against gravity. They facilitate the ipsilateral large extensor muscle groups in all four limbs and the muscles of the neck that support the head (Figure 18-2).

Diagnosis: Otitis Interna (Otitis Media/Interna)

Neurologic Examination

All animals with vestibular disease, regardless of whether they have PVD or CVD, have certain common clinical signs. They typically have a nystagmus, a strabismus that is more apparent when the animal is placed in dorsal recumbency (positional strabismus); a head tilt; a tendency to circle in one direction; and a generalized ataxia. Nystagmus, by convention, is named according to the direction of the fast phase of the ocular movement. For example, an animal with a nystagmus characterized by horizontal movement of the pupil with the fast phase to the right has a “right horizontal nystagmus.” It is important to note that the fast phase is typically away from the side of the lesion; therefore the animal in the example above is likely to have a left-sided vestibular lesion. The head tilt, again by convention, is named according to the side of the head that is lower. In most cases the head tilt is directed toward the side of the lesion. The head tilt is often accompanied by a tendency to lean toward the side of the lesion. In severe cases the dog may roll toward the lesion. Circling, if present, should be described according to the direction of the circle (e.g., left circling) and by the radius of the circle (tight versus broad). Animals with vestibular dysfunction typically present with tight circles and circle toward the side of the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree