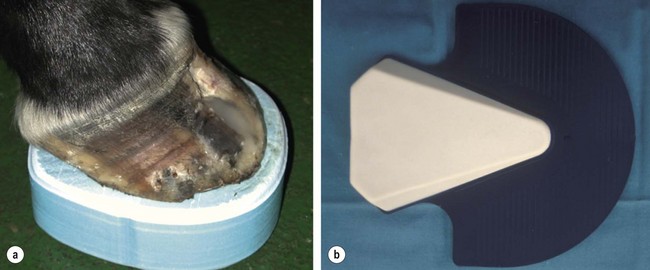

Chapter 16 Seedy toe/separation of the hoofwall Hoofwall avulsions/separations Pododermatitis (bruising and abscess of the foot) Penetrating wounds to the sole Quittor/necrosis of ungular cartilage Lameness due to foot imbalance Fractures of the distal phalanx Bone contusion of the distal or middle phalanx Osseous cyst-like lesions of the distal phalanx Fractures of the navicular bone Distal tendinitis of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) Collateral desmitis of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint Traumatic and degenerative arthritis of the DIP joint Septic arthritis of the DIP joint 16.2 Diseases of the pastern and fetlock region ‘Subluxation’ of the pastern joint Fracture of the middle phalanx Fractures of the proximal phalanx Desmitis of the distal sesamoidean ligaments Distal and proximal digital annular ligament desmitis Collateral ligament desmitis of the metacarpo(tarso)phalangeal joint Desmitis of the intersesamoidean ligament Subchondral bone injury in the fetlock region Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) and osseous cyst-like lesions in the fetlock joint Osteoarthritis of the fetlock joint Fracture of the proximal sesamoid bone Breakdown of the suspensory apparatus Tenosynovitis of the digital flexor tendon sheath and longitudinal tears of the superficial or deep digital flexor tendon Septic tenosynovitis of the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS) Flexural deformity of the fetlock joint 16.3 Diseases of the metacarpus and metatarsus Condylar, metaphyseal and diaphyseal fractures of the third metacarpal/metatarsal bone ‘Bucked shins’/‘sore shins’/dorsal metacarpal disease Proximal palmar/plantar metacarpal/metatarsal pain Superficial digital flexor tendinitis Spontaneous rupture of the superficial digital flexor tendon Deep digital flexor tendinitis Desmitis of the suspensory ligament Desmitis of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon Classification: Vertical defects in the hoofwall occur along the direction of the lamellae of the hoofwall. They can occur in the toe region (toe cracks), quarters (quarter cracks) and heels (heel cracks). Superficial cracks do not involve the sensitive laminae, but deep cracks do. Deep cracks are often accompanied by localized infection of the dermis. Cracks can originate from the coronary band or from the solar margin. They can be partial or complete (from coronary band to solar margin). • Overgrown hoofwall may lead to splitting extending proximally from the solar margin. • Dry, poor quality horn and poor foot balance increase the incidence of cracks. • Defects caused by tearing away of a shoe and part of the wall. • Chronic traumatic defects in the coronary band (false quarters) • High prevalence in the toe region of Draft horses and the medial quarter of Standardbred racehorses. • Obvious hoofwall defect with or without local discharge, heat, or lameness. • Hoof testers and a uni-axial diagnostic analgesia are used to determine clinical significance of the crack. • Pain associated with deep cracks is caused by irritation of the laminar and coronary dermis by differential movement of both sides of the horn defect. • Haemorrhage from repetitive irritation. • Purulent discharge from secondary infection of the exposed dermis. • Prevent with regular good foot care to eliminate foot imbalances. • Application of oil to the hoof to prevent excessive dryness. • Oral administration of biotin and methionine to promote good quality horn growth. • Groove or burn transversely down to healthy continuous horn at the proximal limit of incomplete cracks to prevent progression. • Adequate immobilization of the crack to eliminate irritation and lameness and to allow healing from the coronary dermis down. • A full bar shoe with clips drawn on either side of the crack. • The hoofwall can be lowered either palmar/plantar to the defect (quarter cracks) or directly distal to the defect (toe cracks) to eliminate upward pressure and irritation of the coronary dermis during weight-bearing. • Heartbar shoes and frog pads are used to transfer the load of weight-bearing from the walls to the frog. • Hoof binding resins, acrylics and prosthetic repair materials. These materials should only be used after thorough debridement and elimination of deep-seated infection. • Transversely placed nails, screws and wire, screws and metal plate, or lacing with various materials (e.g. wire, polyester). • Partial hoofwall resection may be needed for complicated cracks that prove refractory to stabilisation techniques. Definition: ‘Seedy toe’ describes a condition in which the dermal and epidermal layers are separated in the toe region of the foot. Newly formed horn follows the line of separation between layers and perpetuates the defect. After some time the separation is visible in the white line in the toe region, and the dermal structures are exposed to ascending infection. • Focal haemorrhage, seroma formation, or inflammation between the layers of the hoof wall. This is followed by a failure of the damaged laminae to produce keratin. • Rotation of the distal phalanx in complicated laminitis. • Onychomycosis has been related to the presence of fungal infection of the hoof wall. • Presence of brown, crumbly horn-like matter along the white line in the toe region. • Non-keratinized void extending from the white line proximally between the layers of the hoof wall. The defect may extend as far proximally as 2/3 of the distance between the solar margin and the coronary band. • Percussion of the dorsal hoofwall may produce a characteristic hollow sound. • Regular cleaning of the defect and shoeing with wide-webbed, flat shoes to increase the base of support for the foot are sufficient in mild cases. • In more severe cases, all separated horn must be removed from the solar margin of the toe to a level where normal interlaminar bond is present. The exposed laminae are medicated under a dressing. This allows newly formed horn to grow distally in a normal direction and restores a normal interlaminar bond. • Moderate lameness is typical following an acute hoof wall avulsion. Severe lameness is indicative of damage to underlying bony, synovial, tendinous or ligamentous structures. Occasionally, a foreign body may be lodged deep between the epidermal and dermal laminae. • If lameness persists, the clinician should be suspicious of deep seated soft tissue or synovial infection or a phalangeal fracture. Treatment: Avulsions without damage to coronary dermis are managed by careful debridement, removal of all loose horn, topical application of antiseptic medication and bandaging until the defect is keratinized. A mixture of sugar and betadine solution works well both as antiseptic and astringent. • Avulsions with coronary band involvement are treated following the same principles. The coronary band must be meticulously reconstructed by suturing. If the wound is severely contaminated or has lost blood supply, delayed primary or secondary closure may be more appropriate. • Complete immobilization of the foot in a distal limb cast for up to 4 weeks is advisable following reconstruction of acute avulsions to allow for primary healing of the coronary dermis. • A foot-pastern cast works well to protect the exposed dermal tissue against further contamination and provides stability during healing. Once the defect is keratinized with a superficial layer of horn, the cast can be replaced with a shoe, and the defect can be repaired with a hoof resin. • If a substantial portion of hoof wall has been excised, a full bar shoe can be applied to provide stability. Definition: Laminitis is a complicated interrelated sequence of inflammatory and vascular events that affect the laminar tissues of the foot and result in varying degrees of breakdown of the interdigitation of the primary and secondary epidermal and dermal laminae of the foot. Pathogenesis: The pathogenesis remains largely unknown, but the disease is thought to result in hypoperfusion, ischaemia and necrosis of the laminae. Four mechanisms have been suggested: 1. Endotoxin-induced laminar microthrombosis. 2. Shunting of laminar blood flow through laminar arteriovenous anastomoses. 3. Vasoconstriction and perivascular laminar oedema. 4. Activated enzyme destruction of the laminar basement membrane. • Laminitis-trigger-factors lead to local enzymatic activation in the horse’s foot, in particular of metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP 2 and 9). The MMPs have been shown to be instrumental in the process of destruction of the basement membrane that is the key structure that bridges the epidermis of the hoof to the connective tissue of the distal phalanx. • In addition it is also thought that alterations in vaso-active mechanisms (mainly vasoconstriction and AVA shunting), induced by imbalances of vaso-active amines, also produce laminar ischaemia and necrosis in the dermal structures of the hoof wall. • In experimental studies intra-cellular glucose deprivation in response to insulin resistance has also been observed to cause laminar detachment by incapacitating cellular desmosomes. • The dorsal coronary dermis, dorsal laminar dermis and dorsal solar dermis have a much less extensive collateral circulation than the palmar dermal tissues in the foot, and are therefore more susceptible to ischaemic necrosis. • The resulting pain causes further release of catecholamines, which cause vasoconstriction and increase ischaemia in the dermal vasculature. • The epidermal-dermal junction becomes oedematous and weakened with loss of interlaminar bond. If this damage extends over a sufficiently large area, suspensory support of the distal phalanx inside the hoof capsule is lost. A combination of the forces of weight-bearing, the pull of the DDFT and dorsal pressure of space-occupying soft tissues (dermal congestion, oedema, seroma and epidermal hyperplasia) result in mechanical separation of the distal phalanx from the hoof wall. • If, as in most cases, mechanical separation is localized to the toe region of the foot, the distal phalanx rotates away from the dorsal hoof wall. This displacement is referred to as palmar rotation as the heels remain suspended by their laminar attachments. • In exceptional cases, the lateral or medial wall may be worst affected, in which case the lateral or medial wall of the distal phalanx may displace distally within the hoof capsule without evidence of rotation of the distal phalanx away from the dorsal wall. This is referred to as lateromedial rotation. • In severe cases in which the suspensory support of all the laminae is lost, the entire distal phalanx drops distally within the hoof without evidence of rotation. This displacement is referred to as ‘sinking’. ‘Sinkers’ have a much worse prognosis than horses with dorsopalmar or lateromedial rotation. • Systemic changes in laminitis can be found in the cardiovascular (tachycardia, hypertension, alterations intrinsic coagulation system) and endocrine systems (increased catecholamines, cortisol, testosterone and plasma renin, and decreased thyroxine). Renal damage (glomerulonephritis, medullary necrosis) and liver disease have also been reported. Aetiology: The aetiology of laminitis is multifactorial, because many different predisposing factors can trigger the same vascular or inflammatory mechanisms. However, in many horses with systemic disease these mechanisms may be caused by the presence of circulating endotoxins. • Nutritional carbohydrate (grain) overload may lead to dysbacteriosis of the intestinal flora, overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria and absorption of endotoxins from the bowel. • Overeating of lush grasses high in fructan may result in hindgut fermentation and lactic acid production, resulting in grass founder. • Systemic infections (e.g. endometritis, pneumonia, enteritis). • Horses recovering from colic surgery are at risk of developing laminitis, possibly because of intestinal dysbacteriosis and the risk of absorption of endotoxin and the frequent presence of blood hypercoagulopathies. • Ingestion of large amounts of cold water. • Electrolyte imbalances (Ca/P and Na/K). • Chronic overloading of the sound limb in severe unilateral lameness. • Strenuous and often prolonged work on hard surfaces. • Long-term or high-dose corticosteroid administration. Corticosteroids increase the vasoconstrictory response of the digital vasculature to catecholamines and serotonin in circulation. • High testosterone concentration has been associated with coagulopathy in the dermal vasculature and may explain why stallions appear to be at higher risk for laminitis. • High oestrogen concentrations have been associated with laminitis in mares with anoestrus or continuous oestrus. Oestrogens are abundantly present in some grasses or legumes. • Exposure to black walnut wood shavings. • Equine pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) (Cushing’s disease) (see Chapter 9). Classification: The clinical presentation of laminitis can be classified into three different categories: 1. Acute laminitis: acute stage of systemic illness with accompanying lameness. 2. Chronic laminitis not associated with a clinically identifiable episode of acute systemic illness and characterized by milder and inconsistent lameness due to low-grade laminal pain and disrupted normal laminar junction. 3. Refractory laminitis: residual lameness due to structural foot changes (rotation or sinking) following resolution of the acute systemic illness. • Horses with acute laminitis show signs of systemic disease and local signs of foot disease. Systemic signs include elevation of heart rate, increased respiratory rate, hypertension (100–200 mmHg) and anorexia. Fever may be present if the horse is septicaemic or endotoxaemic. Evidence of moderate to severe pain is present (sweating, flared nostrils, muscular tremors). Horses are reluctant to move, and if severely affected, may become recumbent. • Laminitic ponies on lush spring pasture have a large neck crest that consists of adipose tissue. This crest tends to become firm to palpation in the early stages of the disease. This form of fat distribution is frequently associated with endocrine abnormalities like PPID or EMS. • A mild form of laminitis in racing Thoroughbreds on a chronic overdose of dietary carbohydrates (i.e. glycogen overload) is characterized by signs of indigestion, low faecal pH (<6.2), poor performance, generalized stiffness and warm feet. • Signs indicative of foot disease are present in horses with laminitis. Most commonly, both front feet are simultaneously affected (except for cases of contralateral overload). The horse has a bounding digital pulse, often in all four limbs. The hoofwall feels abnormally warm, especially in its dorsal half. In severe cases, close examination may show evidence of a depression at the proximal dorsal margin of the coronary band (‘sinker’) or exudative discharge from a separated coronary band. Investigation of the sole may show a convex profile just dorsal to the point of the frog if the distal phalanx has rotated. This same part of the sole may be discoloured by haemorrhagic effusion or even show ulceration with prolapse of the solar dermis (Figure 16.1). The white line may also show evidence of widening, blood infiltration, haemorrhage or separation. • Application of hoof testers or percussion over the sole (dorsal to the point of the frog) and the dorsal wall is usually strongly resented. Response to application to hoof testers is variable when tissue death leads to local loss of sensation. • Horses with laminitis display a typical stance with the forelimbs stretched out in front and the hind limbs placed beneath the body as close as possible to the centre of gravity. The gait is characterized by a typical ‘heel before toe’ foot placement and obvious lameness. • The clinical severity of laminitis may be graded using the Obel grading system. These grades corresponded well to the degree of histopathological damage. • Horses with chronic laminitis show signs of foot lameness similar to those of horses with acute laminitis. However, when the distal phalanx becomes stable, lameness improves, and the foot starts to develop some evidence of long-term deformation. Rings parallel to the coronary band reflect temporary alterations in hoof growth. In laminitis, these rings tend to be closely packed in the toe region and diverge towards the heels, reflecting the discrepancy in rate of hoof growth in these different areas of the foot. The result of decreased toe growth is ultimately a ‘slipper’ foot. Convexity of the sole accompanied by ulceration and prolapse and necrosis of the dermis may be the result of sustained pressure of the tip of the rotated distal phalanx on the solar dermis and its blood supply in this area. • The dead space caused by separation and rotation between the distal phalanx and the dorsal hoof wall in the toe region is gradually filled by epidermal scar tissue. This wedge of epidermal hyperplasia maintains the malalignment of both structures and can be observed as a wide and distorted white line on the solar surface of the foot. • Radiographs are necessary to identify the degree of phalangeal displacement, the presence of infection and chronic bony remodelling of the distal phalanx (Figure 25.6). • Measurements that are useful to determine whether displacement of the distal phalanx has occurred must be performed on a perfect lateromedial radiograph of the foot. Distal phalangeal rotation is assessed by subtracting the angle between the dorsal wall and the sole from the angle between the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx and the sole. Quantification of the degree and progression of distal phalangeal displacement, identified by sequential radiographs, is important prognostically. • Other useful measurements include the proximal and distal dorsal hoof wall thickness (maximum 18 mm for normal Thoroughbreds) and the founder distance (the vertical distance between the level of the dorsoproximal aspect of the hoof wall and the level of the extensor process of the distal phalanx) which should be less than 10 mm in normal horses. The founder distance has been described as the most accurate prognostic indicator for horses with complicated laminitis that have suffered displacement of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule. • Sinking may be difficult to identify radiographically because the dorsal wall and the distal phalanx remain parallel. The presence of sinking can usually be confirmed only by comparing the dorsal hoof wall thickness and founder distance on a marked lateromedial radiograph with normal values or if disease is unilateral by comparing images to the contralateral foot. • The presence of gas opacities on foot radiographs may be indicative of local infection. • Attention should also be paid to evidence of remodelling of the toe of the distal phalanx. Fractures, upwards curling of the apex due to new bone production (‘slipper bone’), irregular radiolucencies and extensive osteolysis with alterations in shape of the apex of the distal phalanx justify a guarded prognosis. • Production of new bone along the dorsal margin of the distal phalanx, with or without rotation, is usually subtle and indicates the presence of laminar tearing. • Radiographic examinations should also include a dorsopalmar view. While all of the above abnormalities are usually recognized in lateromedial views, rarely lateral or medial laminar detachment exceeds dorsal laminar damage and leads to asymmetric sinking of the distal phalanx (lateromedial rotation), which can only be accurately recognized in dorsopalmar projections. • Digital venograms have been used to identify perfusion deficits, which usually indicate a poor prognosis. Treatment: Acute laminitis should be treated as an emergency. Destruction of the laminar bed starts several hours before the first signs of lameness are apparent, and continues to progress if treatment is not initiated. 1. Removal of initiating cause. • Orally administered liquid paraffin, or mineral oil, block absorption of endotoxins from the GI tract. • Horses should be removed from pasture and fed hay and water only. • Systemic infections should be treated vigorously with antibiotics. Antibiotics are also advisable as prophylaxis against secondary sepsis of the foot. • Prior to the administration of antibiotics, anti-endotoxic medication may be considered, as the bactericidal effect of antibiotics may result in an abundance of available bacterial cell wall fragments (i.e. endotoxin) for absorption. Polymyxin-B and endotoxin-specific antibodies are used clinically. These agents have shown the greatest effect when given prior to the release of endotoxins in circulation. • Feeding virginiamycin to horses on a high-grain and pellet feed diet has been proposed as a preventive measure to inhibit caecal lactic acid production and dysbacteriosis. 2. Treatment of peripheral vascular disease. The application of ice on horse’s feet remains controversial. Its presumed beneficial effect lies in causing vasoconstriction during the prodromal stage of laminitis which may reduce the delivery of vasoactive and inflammatory substances to laminar capillaries, which in turn, reduces the activity of tissue-degrading enzymes. Icing following clinical manifestation of disease may reduce oedema formation but potentially aggravates any ongoing ischaemic vascular events. To reduce tissue temperature in the horse’s feet effectively, ice boots should incorporate the entire distal limb up to the carpus/tarsus. • Acetylpromazine to reduce vasoconstriction and hypertension. • Isoxsuprine hydrochloride may counteract early vascular changes in laminitis. • NSAIDs to control digital pain and to interrupt the pain–hypertension cycle. • Potassium chloride is supplemented to correct depletion of potassium. • Sodium is removed from the diet. • Pentoxifylline alters the rheological properties of erythrocytes and improves circulation and oxygen delivery. • Topical application of nitroglycerine may improve local circulation in the foot. 3. Mechanical support of the diseased laminae. • Perineural analgesia and forced exercise MUST be avoided. • The horse should be bedded on a deep soft bed (e.g. shavings, sand, peat) that conforms easily to the shape of the sole and frog. • Pre-shaped frog pads (e.g. Theraflex pads, Lily pads), Styrofoam pads or plaster of Paris slippers help transfer the load of weight-bearing from the walls to the frog (Figure 16.2). 1. General management of the horse. • Limited intake of carbohydrates to control obesity. • Supplement the ration with 30 g of potassium chloride daily. • Supplementation with oral methionine and biotin daily. • Pergolide, cyproheptadine or trilostane for horses with Cushing’s disease. • Guided by good lateromedial foot radiographs. • Removal of all excess horn in the toe region and trimming of the heels to restore normal spatial alignment between the distal phalanx and the hoof. • Dorsal wall resection may be indicated for severely affected horses. Dorsal wall resection is more effective in chronic than acute laminitis. This should never be taken lightly by the treating clinician. Once the dorsal wall is removed, the horse requires close follow-up and intensive aftercare! 3. Therapeutic shoeing for laminitis. • A wide-webbed, seated-out, bar or egg-bar shoe of thick steel with a rolled toe, increases the base of support, minimizes the amount of pressure on the sole, and facilitates breakover of the foot. • A heart-bar shoe may support and immobilize the distal phalanx sufficiently to prevent further rotation and allow for undisturbed revascularization of diseased laminae and restoration of the interlaminar bond. • Derotation or rail shoes have been used to help re-align the distal phalanx inside the hoof capsule. Typically these shoes are placed on the trimmed heel and avoid contact with the dorsal half of the sole and solar margins. • Various types of impression compounds have been used to pack the pain-free part of the solar surface of the foot and spread the load of weight-bearing away from the solar margin. • Tenotomy is performed in the mid-metacarpal region and should be combined with an extended heel derotation shoe. • This procedure may produce significant pain relief and may prevent further dorsal laminar detachment and rotation of the distal phalanx. • Tenotomy appears more effective in chronic laminitis than in horses with acute laminitis, sinking or foot sepsis. • Tenotomy should be regarded as a salvage procedure for valuable breeding horses. The beneficial effects may only be temporary. The procedure can be repeated distally to the previous tenotomy site. • Similar relief has also been described following inferior check ligament desmotomy. • In one study, 59% of horses were alive for at least 2 years after a tenotomy. Prognosis: Most horses with acute laminitis recover with conservative treatment, without the use of radical trimming or shoeing. • If a horse with acute laminitis shows no rotation by day 10, it can come off medication by day 20 and can usually be safely considered as recovered by day 60. • The prognosis becomes unfavourable when: • Prognosis becomes hopeless in cases of:

Orthopaedics 2. Diseases of the foot and distal limbs

16.1 Diseases of the foot

Seedy toe/separation of the hoofwall

Hoofwall avulsions/separations

Laminitis

Obel Grade 1: shifting weight.

Obel Grade 1: shifting weight.

Obel Grade 2: typical laminitic gait (stiff and stilted as if ‘walking on egg shells’). Lifting of each front foot and resting on the contralateral foot are possible.

Obel Grade 2: typical laminitic gait (stiff and stilted as if ‘walking on egg shells’). Lifting of each front foot and resting on the contralateral foot are possible.

Obel Grade 3: reluctance to walk with typical laminitic gait. Lifting of each front foot and resting on the contralateral foot are not possible.

Obel Grade 3: reluctance to walk with typical laminitic gait. Lifting of each front foot and resting on the contralateral foot are not possible.

Secondary infection is a common feature of chronic laminitis. These infections can range from simple subsolar and laminal abscesses to more extensive infections that can lead to septicaemia. Infection characteristically causes a sudden exacerbation of lameness.

Secondary infection is a common feature of chronic laminitis. These infections can range from simple subsolar and laminal abscesses to more extensive infections that can lead to septicaemia. Infection characteristically causes a sudden exacerbation of lameness.

Endocrine function tests may be necessary to identify the presence of endocrine abnormalities like PPID or EMS.

Endocrine function tests may be necessary to identify the presence of endocrine abnormalities like PPID or EMS.

the acute phase continues for more than 10 days.

the acute phase continues for more than 10 days.

digital pain is uncontrollable and the horse is mostly recumbent.

digital pain is uncontrollable and the horse is mostly recumbent.

blood pressure remains higher than 200 mmHg for more than a few hours.

blood pressure remains higher than 200 mmHg for more than a few hours.

secondary infection is present.

secondary infection is present.

displacement of the distal phalanx has occurred. Full athletic recovery is still possible for horses in which rotation does not exceed 5.5°.

displacement of the distal phalanx has occurred. Full athletic recovery is still possible for horses in which rotation does not exceed 5.5°.

Pododermatitis (bruising and abscess of the foot)