Chapter 1 Origin and Evolution of Virulence

Virulence, simply defined, is microbial specialization that facilitates replication in hosts. The resulting damage to the host may be so minimal that it yields no clinical signs, or so great that it results in death. Host and pathogen are often equal players in the initiation, progression, and outcome of the encounter, and are in ceaseless evolutionary conflict.

TRAITS OF PATHOGENS

Finding and occupying a niche is the next challenge. Multitudes of commensal bacteria, fungi, and protozoa derive their living from residence in or on hosts, and, not surprisingly, make no effort to welcome interlopers. Some opportunistic pathogens cannot succeed in this endeavor without outside assistance, as with Clostridium difficile infectionin humans subjected to systemic antimicrobial therapy (Figure 1-1).

ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF VIRULENCE

Another aspect of dogma was that a well-adapted parasite is a benign parasite. Pathogens were believed to evolve uniformly toward a benign coexistence, or mutualism, allowing more effective reproduction in association with a host. Lewis Thomas said, of C. diphtheriae relating to human hosts, “It is certainly a strange relationship, without any of the straightforward predator-prey aspects that we used to assume for infectious disease. It is hard to see what the diphtheria bacillus has to gain in life from the capacity to produce such a toxin. Corynebacteria live well enough in the surface of human respiratory membranes, and the production of a necrotic pseudomembrane carries the risk of killing off the host and ending the relationship. It does not, in short, make much sense, and appears more like a biological mix-up than an evolutionary advantage.”

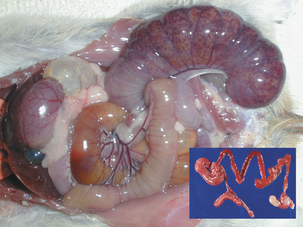

Microbial virulence is on average strongly dependent upon efficient transmission; adding a low infectious dose further increases the efficiency. “Dead-end” hosts are not uncommon, but this is likely not a fully evolved virulence strategy. For example, Leptospira interrogans serovar icterohaemorrhagiae is commonly found in feral rodents, in which it causes relatively minor pathology (Figure 1-2). However, humans and other species infected by contact with rodent-contaminated environments are likely to develop severe, frequently fatal, disease. Transmission from rodent to rodent and rodent to environment is common, but infected humans (for example) are unlikely to transmit the infection. Another example is provided by the relationship of Neisseria meningitidis to human hosts; this organism is a commensal of the human nasopharynx, but can enter the cerebrospinal fluid and produce meningitis. Transmission from the nasopharynx is common, but organisms sequestered in cerebrospinal fluid are not available to other hosts. The host with meningitis is thus a dead-end host.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree