52 Orbit and globe – introduction

THE ORBIT

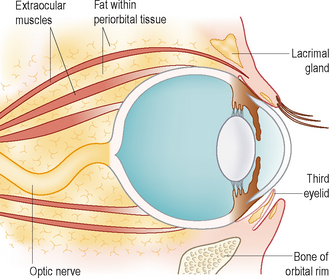

The orbit is the bony fossa which separates the eye from the cranial cavity. Many bones contribute to it – the frontal, lacrimal, maxillary, zygomatic, pterygoid, palatine and sphenoid. The orbit surrounds and protects the globe while providing a route for vessels and nerves to access the eye. In addition to the eye itself, this region contains the extraocular and retrobulbar muscles, optic nerve, lacrimal and nictitans glands, and part of the zygomatic salivary gland, along with the blood vessels and nerves (cranial nerves II, III, IV, V, VI and VII) (Figure 52.1). Connective tissue and fat are also present.

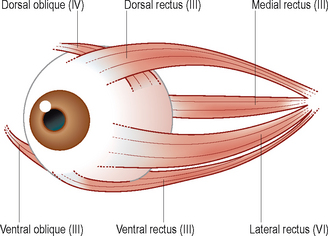

The extraocular muscles are located within the orbit. They are attached to the globe and provide ocular motility. Together with the retrobulbar muscle they form a cone shape with the apex at the optic foramen. They are normal striated muscle. There are six extraocular muscles for each eye: the four rectus muscles (dorsal, ventral, medial and lateral – which pull the eye in their respective directions), together with the dorsal oblique (which pulls the dorsolateral aspect of the globe ventromedially) and the ventral oblique (which pulls the eye mediodorsally) (Figure 52.2). The extraocular muscles are innervated by the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III), apart from the lateral rectus muscle which is innervated by the abducens nerve (cranial nerve VI) and the dorsal oblique muscle which is supplied by the trochlear nerve (cranial nerve IV). Thus, if there are abnormalities with the cranial nerves, this can alter both the position of the eye within the socket and affect its movement. These findings can aid with the localization of any lesion and form an important part of neuro-ophthalmology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree