Chapter 13 Ocular Diseases

DISEASES OF THE ORBIT

Inflammatory Orbital Diseases

Orbital Cellulitis

Signs.

Acute orbital cellulitis patients have rapid onset of a warm, painful swelling of the orbital region, lids, and nictitans, chemosis of the conjunctiva, and a degree of exophthalmos. Fever is usually present, and the exophthalmos may allow exposure keratitis to occur as the globe is pushed outward to such an extent that the lids no longer protect the central cornea (Figure 13-1).

Treatment.

The prognosis for acute orbital cellulitis is good if medical and nursing care can be provided. Most cases resolve within 5 to 7 days with the aforementioned therapy.

Chronic orbital cellulitis or abscessation requires localization of the lesion to allow surgical drainage. Needle aspirates or ultrasound-guided needle aspirates confirm the location of the infection before drainage. Knowledge of the skull and orbit anatomy is helpful in avoiding injury to important structures when attempting to lance an orbital abscess (Figure 13-2). Most abscesses harbor A. pyogenes. Therefore systemic penicillin (22,000 U/kg once daily) should be used for 1 to 2 weeks following surgical drainage of the lesion. Gentle flushing of the abscess cavity should be performed once or twice daily, and warm compresses should be used if exophthalmos is severe enough to raise concern of exposure keratitis. Recurrent orbital abscesses or chronic cellulitis will dictate more intensive diagnostic work, including ultrasonography, radiographs, and culture-sensitivity testing to rule out foreign bodies and resistant organisms.

Inflammation of the Tissues Adjacent to the Orbit

Signs.

Mild to marked unilateral exophthalmos associated with bony expansion of the ipsilateral frontal or maxillary sinus, depression, mild ocular discharge, and fever constitute the major signs in chronic sinusitis (see Chapter 4). Fever may be transient or intermittent, depending on patency of the frontomaxillary-nasal drainage. When purulent material cannot escape, bony expansion of the sinus and fever are more constant. Purulent material can escape through sinus openings into the nasal cavity and cause unilateral purulent nasal discharge. Chronic infection causes extreme softening of the bones surrounding the sinuses and allows for variation in the appearance of the skull. The caretaker may report that the animal’s skull appears swollen on some days but normal on others.

Diagnosis.

Radiographs are useful to confirm sinusitis, and aspirates for cytology and culture allow appropriate antibiotic selection. Biopsies are essential when presence of neoplasia is suspected. Radiographs are very useful to detect cheek/tooth root abnormalities in chronic maxillary sinusitis patients.

Treatment

Frontal Sinusitis

Trephining of the skull in at least two areas is necessary to provide adequate drainage and lavage of chronic frontal sinusitis in adult cattle. Trephine holes should be 1.75 to 2.5 cm in diameter and drilled at the cornual area (former area of horn) and 3.75 to 4.50 cm off the skull midline along a transverse line drawn through the caudal bony orbit (see Figures 4-10 and 4-11,A and B). Some references suggest a third opening dorsocaudal to the orbit, but in Dr. Rebhun’s experience, this was associated with complications such as entering the orbit. Calves and heifers do not have an extensive frontal sinus except at the cornual area, and trephining the sinus of heifers less than 15 to 18 months of age may lead to invasion of the calvarium.

Neoplastic Disease

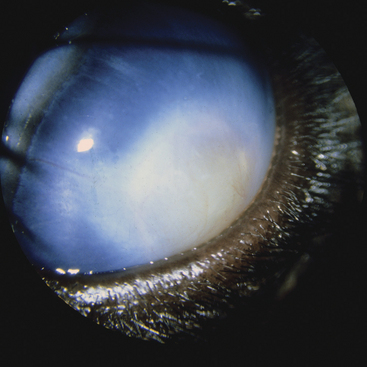

The most common orbital tumor in dairy cattle is lymphosarcoma. Tumors may be unilateral or bilateral and cause progressive acquired exophthalmos with exposure keratitis or proptosis (Figure 13-3). Because some Jersey, Ayrshire, and Holsteins cows have relative bilateral exophthalmos (i.e., are “bug-eyed” as a normal appearance), early detection of acquired exophthalmos may be difficult for the average caretaker. Therefore severe exophthalmos and exposure damage to the globe secondary to orbital lymphosarcoma may be reported to be acute by the caretaker. This history implies a higher likelihood of orbital cellulitis than neoplasia. However, thorough physical examination to detect other neoplastic target areas and absence of fever usually allows a proper diagnosis. In fact, even though the retrobulbar lymphoid masses obviously have been present and enlarging for some time before pathologic exophthalmos, the pathology may appear very acute once the degree of exophthalmos prevents the eyelids from completely protecting the central cornea. At this point, exposure damage and desiccation of the central cornea coupled with severe blepharospasm, chemosis, and lid swelling dramatically worsen the appearance of the eye (Figure 13-4). A visual eye with moderate exophthalmos but without exposure keratopathy may change to a blind, proptosed eye with complete corneal desiccation in less than 48 hours.

Figure 13-4 Retrobulbar lymphosarcoma causing exophthalmos, chemosis, and severe exposure keratopathy.

Diagnosis depends on finding other evidence of lymphosarcoma in the patient. Enlarged lymph nodes, melena, cardiac abnormalities, uterine masses, or neurologic signs also may be present. In some patients, the retrobulbar masses are the signal lesions, and other lesions may be undetectable. In this instance, blood for a CBC and bovine leukemia virus (BLV) agar gel immunodiffusion or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test is indicated to add supportive data. Most cattle with clinical lymphosarcoma test positive for BLV. This test is supportive but not conclusive because most BLV-positive cattle never develop tumors. Unlike cases with an orbital abscess, serum globulins and inflammatory markers are often normal in cattle with lymphosarcoma. Aspirates from the retrobulbar region may be helpful in some affected cattle. In questionable cases, the proptosed globe should be enucleated to alleviate the cow’s pain and allow collection of tumor material from the orbit for cytology or histopathology. The lymphoid tumors can be palpated along the periorbita and in the orbital cone in most affected cattle. Although the globe usually is free of tumor, rare cases have had conjunctival, corneal, lid, or scleral involvement.

Squamous cell carcinoma may occur in an orbital location but usually is preceded by lid, conjunctival, or corneal squamous cell carcinoma. Orbital squamous cell carcinomas are locally invasive, tend to metastasize, and have a grave prognosis. Carcinomas of respiratory epithelial origin also have been observed in older dairy cattle (more than 8 years of age). These tumors are slow growing over months to years; cause progressive unilateral exophthalmos, inspiratory stridor, and reduced airflow in the ipsilateral nasal airway; and may cause ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome (see Figures 4-5 and 4-6). Although prognosis is poor, affected cattle may be productive for 1 to 3 years with these slow-growing tumors.

Neurologic Diseases

Horner’s syndrome is the most common neurologic disease of the orbit observed in dairy cattle. The features of ptosis, mild miosis, and ipsilateral facial warmth coupled with dryness of the muzzle and nares are well described. Horner’s syndrome in cattle is most commonly caused by injury to the cervical vagosympathetic trunk by carotid artery hematomas, cellulitis of the neck, or direct injury by traumatic venipuncture of the jugular vein (Figure 13-5). Other causes are rare, but the syndrome has been observed with skull tumors (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma) that invade the orbit causing upper respiratory dyspnea and decreased air flow from one or both nostrils, as well as Horner’s syndrome.

DISEASES OF THE GLOBE

Developmental Diseases of the Globe

Etiology and Signs

Developmental malformations of the globe result in megaglobus or microphthalmos (Figure 13-6). Anophthalmos, absence of all ocular tissue, is seldom an appropriate term because histologic section of orbital tissue in suspected anophthalmos cases almost always produces some evidence of ocular tissue, thus making microphthalmos the proper term. Congenital microphthalmia may be unilateral or bilateral in calves. Physical, toxic, and infectious causes have been suggested but seldom are confirmed to explain all sporadic microphthalmia. In utero infection with bovine virus diarrhea virus (BVDV) during the middle trimester occasionally has resulted in microphthalmia.

Genetic causes of microphthalmia appear common in dairy cattle. In Guernsey and Holstein calves, the defect has been linked with cardiac and tail anomalies. Most commonly these calves have a ventricular septal defect and wry tail, as well as unilateral or bilateral microphthalmia. Tail defects other than wry tail have been observed in some Guernsey and Holstein calves with microphthalmia and/or ventricular septal defect. These include absence of a tail, short tail, absence of some sacral vertebrae in addition to coccygeal vertebrae, and atresia ani coupled with absence of vertebrae (see Figure 13-6). In Guernseys, these malformations are thought to be caused by a recessive trait, but in Holsteins, the exact mode of inheritance is unknown.

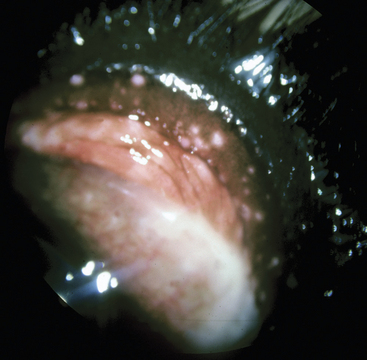

Congenital megaglobus results from anterior cleavage abnormalities or multiple congenital anomalies producing glaucoma in utero. Dr. Rebhun observed several calves with anterior cleavage anomalies. The lens placode had not separated from the surface ectoderm during the development of those eyes. Subsequent influx of mesodermal tissue forming the corneal stroma, endothelium, Descemet’s membrane, and iris surrounds the lens. The resulting absence of an anterior chamber causes congenital glaucoma and buphthalmos. All cases to date have been unilateral, and the affected eye is noticeably buphthalmic at birth, with corneal edema, central dense opacity (lens in cornea), and no discernable anterior chamber (Figures 13-7 and 13-8).

Figure 13-7 Congenital buphthalmos and glaucoma in the right eye of a calf with an anterior cleavage defect.

Convergent strabismus with or without associated relative exophthalmos has been described as an inherited trait in Jersey and Shorthorn cattle. It also has been observed occasionally in Ayrshires, Holstein, and Brown Swiss cattle (Figure 13-9). Bilateral relative exophthalmos (“bug-eyed cows”) is a condition that has been observed in several dairy breeds and probably is a genetic trait. Exophthalmos in these cows does not progress to a pathologic state or exposure keratitis because the eyelids still cover the cornea adequately. However, pigment migration occurs over the bulbar conjunctiva and peripheral cornea as a result of exposure of the globe to dust, air, or debris in some affected cattle.

Acquired Diseases

Acquired megaglobus may follow severe intraocular inflammation of exogenous or endogenous cause. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK), trauma, and uveitis are the usual causes of anterior synechiae, lens luxation, and adhesions that disturb aqueous outflow, thereby creating glaucoma. Endophthalmitis and panophthalmitis secondary to septic uveitis or ocular perforation may also cause megaglobus. If megaglobus is severe enough to cause exposure keratitis, the affected globe should be enucleated to prevent eventual perforation or panophthalmitis. Adult dairy cattle with severe megaglobus treated by enucleation become comfortable and return to anticipated production within several days (Figure 13-10). Therefore it is important that acquired megaglobus is not diagnosed erroneously as a retrobulbar neoplasia.

Less frequently, megaglobus follows intraocular neoplasia or granulomatous infections of the uveal tract. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most frequent tumor to invade the globe, and tuberculosis must be considered when a granulomatous infection of the globe is diagnosed.

DISEASES OF THE EYELIDS

Inflammatory Diseases

Etiology and Signs

Allergic reactions commonly result in eyelid swelling and conjunctival edema (chemosis). These signs usually but not always are accompanied by other systemic signs such as urticaria, skin wheals, facial swelling, and other mucocutaneous junctional swellings. Allergic reactions may occur secondary to iatrogenic administration of antibiotics, intravenous (IV) fluid, blood transfusions, and biologics. Similar reactions accompany individual animal sensitivities to various feedstuffs, plants, and milk allergy (see Chapter 7).

Neoplastic Diseases

Etiology and Signs

Fibropapillomas or “warts” are the most common tumor to involve the eyelid of calves and young cattle. In most instances, the tumors are raised, firm masses with a gray crusty covering (see Figure 7-1).

Lymphosarcoma rarely infiltrates the eyelids as a diffuse lid swelling with conjunctival chemosis.

Treatment

Fibropapillomas normally are self-limiting within 4 to 6 months and do not require treatment. Persistent or large fibropapillomas (Figure 13-11) may interfere with eyelid function or cause corneal injury and require surgical treatment via cryosurgery or sharp dissection.

Squamous cell carcinomas tend to be locally invasive and may metastasize in some neglected cases. This tumor requires aggressive early therapy to prevent progression, or the cow will be lost. Many therapeutic options exist for early, small squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelids, whereas enucleation, radical exenteration, or culling may be required for large lid lesions. Recognition of early tumor formation when the mass is less than 2.0 cm in diameter allows consideration of cryosurgery, radiofrequency hyperthermia, radiation (if available), sharp surgery, and immunotherapy. Large lid masses (greater than 5.0 cm in diameter) are less likely to be treated successfully because destruction or removal of this much lid tissue may lead to ocular exposure damage (Figure 13-12). These large tumors also are more likely to invade adjacent adnexal tissue, orbital ligaments, periorbita, and bone of the skull. Tumors at the medial canthus are extremely dangerous because they need to advance only 2.0 cm along the medial orbital ligament before entering the bony orbit.

DISEASES OF THE CONJUNCTIVA

Inflammatory Diseases

Etiology and Signs

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) virus, the herpes virus 1 of cattle, may cause a severe endemic conjunctivitis in nonvaccinated cattle. The conjunctivitis may be the only lesion observed in sick cattle or may occur in conjunction with the typical respiratory form of IBR. The disease has been observed in heifers and adult cattle. Typical lesions include severe conjunctival hyperemia, heavy ocular discharge that converts from serous to mucopurulent over 48 to 72 hours, and the presence of multifocal white plaques in the palpebral conjunctiva (Figure 13-14). The lesions may be unilateral or bilateral and affect 10% to 70% of the herd. The plaque lesions are pathognomonic for IBR. Affected adult cattle have high fever (105.0 to 108.0° F/40.56 to 42.22° C), depression, and decreased milk production. Milking cattle with the conjunctival form of IBR appear ill regardless of whether the respiratory form coexists. Heifers with the conjunctival form of IBR may have fever and mild systemic illness but seldom appear as sick as adult milking cattle. The reason for this difference is not known but may be related to the stress of lactation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree