Chapter 2 Therapeutics and Routine Procedures

VENIPUNCTURE

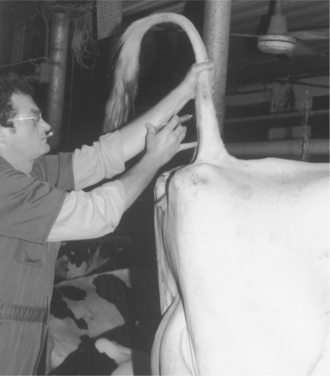

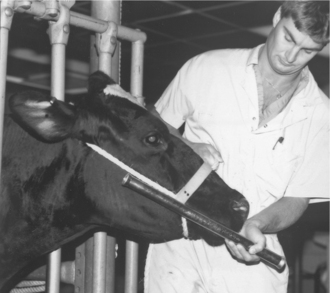

The jugular vein is the major vein used to administer large volumes of intravenous (IV) fluids in dairy cattle. The middle caudal vein (“tail vein”) is used for collection of blood samples and for administration of small volumes (less than 5.0 ml) of medications. If the tail vein is used for drug administration, only aqueous agents that will be nonirritating (should they leak perivascularly) should be used because it is harder to avoid some degree of leakage at this location than when a well-seated needle is used in the jugular vein. The mammary vein should not be used for either blood sampling or drug administration because complications of mammary venipuncture may have disastrous results, such as mammary vein thrombosis or phlebitis (see Figures 3-20 and 3-21), persistent unilateral mammary edema, and endocarditis. In general, it is contraindicated to use the mammary vein therapeutically unless the cow has a life-threatening illness and is in a compromised position, such that the jugular vein is inaccessible. Cattle with bilateral jugular vein thrombosis also may necessitate the risk of mammary vein venipuncture. In severely dehydrated calves, it is necessary occasionally to use a cephalic or dorsal metatarsal vein should the jugular veins become thrombosed during repeated fluid administration. Before any venipuncture, the overlying skin and hair should be moistened and smoothed down with alcohol. The vein should be “held off” by applying digital pressure proximal to the heart from the site of venipuncture (Figure 2-1). Neophytes seldom apply pressure of sufficient magnitude or duration before venipuncture and consequently have difficulty palpating or viewing the distended vein. Experienced clinicians are very patient and allow the vein adequate time to fill with blood, making venipuncture easier. Choke ropes or chains seldom are necessary in routine jugular venipuncture but may be helpful in extremely dehydrated patients. Utilizing gravity by allowing the head to hang over the side of a raised platform or table or even by hanging the calf over a stall divider or gate can distend the jugular vein significantly to facilitate venous access in very dehydrated calves. Commercial instruments such as Witte’s neck chain and Schecker’s vein clamp are available aids used in Europe.

Jugular venipuncture may be performed with a variety of needles, but the needle must be suited to the drug’s viscosity, volume, and the duration of time anticipated for delivery. Stainless steel 14-gauge needles that are 5.0 to 7.5 cm in length are favored for most fluid infusions that do not exceed 2 to 4 L and that are to be administered promptly. Although many practitioners use disposable 14-gauge needles that are 3.75 cm in length, these needles are too short and so sharp that, with minimal patient struggling, such complications as laceration of the intima of the vein or perivascular administration of medications may occur. These shorter, disposable needles are acceptable for recumbent or extremely well-restrained cattle only. In general, venous complications such as thrombosis and perivascular injections are more common with the shorter needles. The longer 5.0- to 7.5-cm stainless steel needles are long enough to remain well positioned within the vein, are less sharp and therefore less likely to lacerate the intima of the vein and thus tend to cause less frustration to the practitioner faced with an unruly patient. The disadvantage of stainless steel 14-gauge needles is that they require cleaning, sterilization between uses, and periodic sharpening with an Arkansas stone. Cleaning and sterilization between uses are extremely important in preventing spread of bovine leukemia virus (BLV) and bacterial infections. Although most practitioners prefer 14-gauge needles, some practitioners successfully use 12-gauge, 5.0- to 7.5-cm stainless steel needles to allow an even more rapid administration of solutions such as dextrose and balanced electrolytes through the jugular vein. Careful pressure over the venipuncture site following removal of the needle is important in preventing hematoma formation, which may contribute to venous thrombosis.

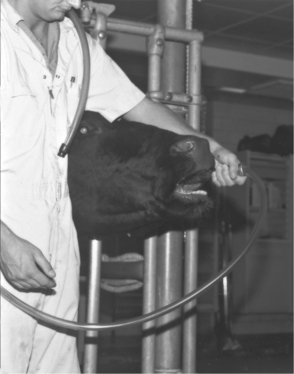

Puncture of the middle caudal vein (“tail vein”) is performed by inserting a needle on the ventral midline of the proximal tail. The exact distance from the anus may vary depending on the animal’s size, but the site is usually 10.0 to 20.0 cm from the anus. The vein and artery are thought to run side by side as far as the fourth caudal vertebrae; the artery then usually runs ventral to the vein. However, this anatomy often varies. When performing tail vein venipuncture, the clinician must provide restraint by elevating the tail perpendicular to the top line. Forgetting to do this may result in a painful lesson in restraint. The tail is raised with the clinician’s less adroit hand, and the venipuncture is performed with the preferred hand (Figure 2-2). Needles already should be connected to the syringe that holds the drug or with a Vacutainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) partially inserted so that the entire procedure can be done with one hand. Needles should be 18 or 20 gauge and 2.5 to 3.75 cm in length. The needle is inserted on the ventral midline perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tail and advanced until it gently strikes bone. Aspiration of blood is then attempted. If successful, the drug is administered or blood collected. If unsuccessful, the needle is gently backed off the bone 1 to 5 mm, and aspiration is attempted again. Use of the middle caudal vein for administration of small volumes (less than 5.0 ml) of medications and blood collection has largely replaced jugular venipuncture for these procedures in dairy cattle. Tail bleeding is far less stressful to the patient, avoids bellowing and excessive restraint, and is quicker because one person performs both restraint and venipuncture. Although primarily valuable for blood collection in adult daily cattle, the tail vein may be used for blood collection in heifers of 300 kg or more. The procedure is more difficult in heifers of this size, however. Tail bleeding should not be attempted in young calves, lest permanent damage to caudal vessels occur.

Selection of appropriate needles for intramuscular (IM) injections in cattle requires consideration of density or viscosity of the drug to be administered, size of the patient, and desired depth of injection. Needles of too narrow bore prolong the time necessary for injection, often causing increased patient apprehension, struggling, or kicking. Needles too large of bore allow leakage of the administered drug from the site and cause more bleeding. Most aqueous-based drugs can be administered IM via an 18-gauge, 3.75-cm needle in adult cattle, whereas injection of oil-based or more viscous drugs (e.g., penicillin, oxytetracycline HCL) is facilitated by a 16-gauge, 3.75-cm needle. Most practitioners use disposable needles for IM injections to avoid the bothersome task of cleaning and sterilizing used needles. Increasing concerns regarding carcass spoilage as a result of the IM administration of therapeutic and biologic agents in grade dairy cattle have prompted a move toward subcutaneous administration of many products (antibiotics, hormones) that were previously given IM. Carcass trimming with subsequent lost revenue from meat is a relevant issue because the slaughter value of a culled dairy cow represents a significant revenue stream for many modern producers.

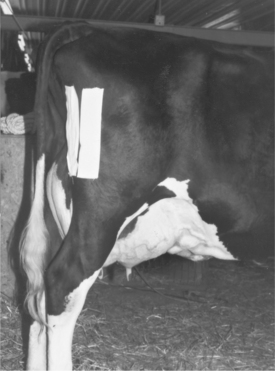

The primary site for IM injections in cattle is the caudal thigh muscles, especially the semimembranosus and semitendinosus. Occasionally the caudal biceps femoris is used as well (Figure 2-3). The gluteal region should not be used for IM injections in calves or adult dairy cattle because of the relative lack of musculature in a “dairy-type” animal. Injections in this area risk temporary or permanent injury to the sciatic nerve branches traversing the gluteal region when repeated IM injections or an IM injection of irritating drugs is necessary. Gluteal injections are especially contraindicated in dairy calves (Figure 2-4). Although many textbooks and publications advocate IM injections in the gluteal regions, this procedure should be avoided in dairy cattle.

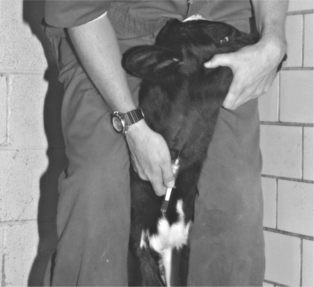

Figure 2-4 Sciatic nerve injury secondary to intramuscular injection in the gluteal region of a Holstein calf.

Other available sites for IM injections include the triceps brachia (triceps) and the caudal cervical muscles (Figure 2-5). From a practical standpoint, dairy cattle generally are more excited by injections in their front end than by injections in their hind end. If a cow is well restrained with a halter, IM injections can be made safely in the caudal cervical or triceps region. In poorly restrained cattle, those injection sites frequently cause wild and aggressive behavior. Most dairy cows tolerate IM injections in the caudal thigh muscles without kicking. However, unnecessary prolongation of the injection because of improper needles, multiple IM injections, or failure to prepare the patient for the “shot” all may lead to violent behavior. In addition, some dairy cattle are dangerous and require additional restraint before IM injections to avoid injury to themselves or their handlers.

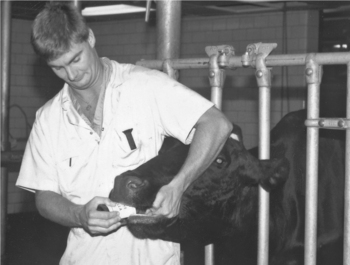

The caudal cervical muscles in a calf provide an easily accessible site for IM injections of less than 5.0 ml of nonirritating solutions. The clinician can restrain the calf by straddling its neck and bending the calf’s head to one side while the injection is made (Figure 2-6).

Selecting a clean site (free of manure and moisture) and swabbing it with 70% alcohol should precede IM injections. The needle is held by the hub between the thumb and forefinger, and the cow is slapped repeatedly with the back of the clinician’s hand near the site of the injection. Quickly rotating the hand, the clinician then slaps the needle into the selected IM site. The needle must be submerged all the way to its hub. A visual inspection for blood coming from the needle is made, and if none is seen, the syringe of medication is quickly attached to the needle. Aspiration on the syringe plunger will detect needles placed within vessels. If blood is aspirated, the injection is aborted, and the needle should be placed at a different site. If no blood is observed, the injection is made as quickly as possible. Up to 20 ml of drug may be deposited at an IM site in an adult cow, but probably no more than 5 ml should be placed at any one site in a young calf. Consideration of the drug’s irritability to tissue may also influence specific volumes deposited at IM sites.

It is important to avoid injury or irritation to the forelimbs when injections at these sites are made, and irritating drugs or excessive volumes should be avoided, lest the animal experience pain associated with forelimb motion (Figure 2-7). To speed the administration, a large-gauge needle, such as a 14-gauge needle, should be used for adult cattle, and a 16-gauge needle should be used for calves. A disposable 3.75-cm needle is sufficiently long for this purpose. A 500-ml bottle of calcium borogluconate usually is divided into three or four sites (e.g., left and right side front of forelimbs, left and right side caudal to forelimb), whereas an antibiotic injection may be made at one site in the morning, another in the evening, and yet another site the following day. Calves requiring subcutaneous balanced fluid solutions may receive 250 to 1000 ml at a single site, depending on the size of the patient. During the injection, the bleb of fluids should be gently compressed and spread out by the clinician to distribute the fluids, improve absorption, and decrease leakage following withdrawal of the needle. Subcutaneous injections of irritating drugs or dextrose-containing solutions must be avoided.

In adult dairy cattle, a needle at least 5.0 cm in length would be necessary for intraperitoneal injection, and risks of damage to viscera are minimized by rolling a recumbent cow to her left side before puncturing the right paralumbar fossa.

Complications of jugular IV injections include hematoma formation, thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, perivascular injections of irritating drugs, endocarditis, and Horner’s syndrome (see Chapter 3, Figures 3-19 and 3-5). The most irritating and dangerous drugs commonly administered IV in cattle are 40 to 50% dextrose, 20% sodium iodide, and calcium. Avoiding perivascular deposition of these three drugs is extremely important. Good technique and adequate restraint are the keys to avoiding complications from IV injections.

Complications of caudal vein injections include hematoma formation, thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and sloughing of the tail (Figure 2-8).

Figure 2-8 Complete sloughing of the tail in a Holstein cow following perivascular injection of phenylbutazone.

Complications of IM injections include tissue necrosis with subsequent lameness; peripheral nerve injury, especially sciatic nerve branches in the gluteal region or tibial branches in the caudal thigh muscles of calves; clostridial myositis; and procaine reactions. Peripheral nerve injury can be prevented best by avoiding the gluteal region when performing IM injections. In calves, palpation of the groove separating the biceps femoris and semitendinosus proximal to the stifle and injecting medial or lateral to this groove will help avoid sciatic nerve injury. Clostridial myositis is always a risk when injecting irritating drugs that may create a focal area of tissue necrosis and subsequent anaerobic environment in the IM site. Although Clostridium chauvoei (blackleg) spores may be in tissue locations already, most clostridial myositis secondary to IM injections is caused by Clostridium perfringens or Clostridium septicum. Currently prostaglandin solutions are the most commonly incriminated solutions to result in clostridial myositis (see Chapter 15, Figures 15-1 and 15-2). Using sterile syringes, sterile needles, and avoiding contamination of multidose drug vials are important preventive measures. In addition, IM injections should not be made through skin covered by dirt or manure without first cleaning the site.

Complications of subcutaneous injections include chemical and infectious inflammation. Chemical inflammation with eventual tissue necrosis and sterile abscessation is common should dextrose or calcium dextrose combinations be injected subcutaneously. Infectious inflammation, phlegmon, and eventual abscessation may result from poor skin-site preparation or technique. Common signs include painful, diffuse swellings that gravitate ventrally from the subcutaneous injection site, lameness and stiff gait caused by pain associated with forelimb movements, fever, and depression (Figure 2-9). Treatment consists of hydrotherapy, warm compresses, analgesics, and eventual drainage.

Various cannulas and commercial mastitis tubes are available for intramammary infusions. Individual sterile plastic cannulas (2-cm) with syringe adapters are used most commonly for infusion of noncommercial mastitis products, whereas stainless steel 14-gauge, 5.0-10-cm blunt-tip teat cannulas are sometimes used to facilitate milk-out from injured teats or for diagnostic probing of obstructed teats.

In all instances and regardless of the cannula used, the teat and teat end should be prepared aseptically before insertion of the cannula through the streak canal. After cleaning the teat thoroughly, the teat end should be swabbed repeatedly with alcohol before the cannula is inserted and again after the cannula is removed (see also Chapter 8). Large-volume infusions (greater than 100 ml) may be administered via gravity flow with the aid of simplex tubing and a sterile teat cannula.

BALLING GUNS

Both types of balling guns are safe when used properly, and both are lethal weapons if used improperly. Before passing a balling gun into the patient’s oral cavity, a quick assessment of the patient’s size is mandatory. The administrator of the bolus using a balling gun should ask the following questions: Where is the pharynx in this patient? How much of the instrument should be advanced into the oral cavity? Balling guns passed too far caudally abut the soft palate or dorsal pharyngeal wall, thereby allowing pharyngeal injury when forceful expulsion of a bolus or multiple boluses occurs. In adult Holstein cattle, commercial balling guns are in correct position when the holding finger rings (not the plunger finger ring) are resting against the commissure of the patient’s lips (Figure 2-10). However, this same position in a Jersey cow or a yearling Holstein places the bolus too far caudally in the oral cavity, thereby risking pharyngeal injury when the bolus is forcibly discharged.

STOMACH TUBES

Before passage of a stomach tube through the oral cavity of a cow, a speculum or gag must be used to guard the tube. Both the tube and some types of specula have the potential to cause iatrogenic injury. Stomach tubes should have smooth, tapered ends, appropriate flexibility, and measurement markers. A variety of gags are used to prevent cattle from chewing on or “eating” the stomach tube. Properly used gags present little potential for patient injury. However, a pipe and Fricke speculum are the oral specula used most commonly in dairy cattle and are potentially dangerous instruments. The length of a Fricke speculum exceeds the length of a cow’s oral cavity so that the operator can safely hold a portion of the speculum external to the patient’s mouth. Introducing a Fricke speculum too far caudally into the patient’s oral cavity causes repeated gagging, coughing, and interferes with passage of the stomach tube because the tube repeatedly contacts the pharyngeal wall rather than the pharyngeal cavity when advanced. Overzealous forcing of the tube in this incorrect position results in injury to the patient. Before using a Fricke speculum, the patient should be “sized up” to determine how much of the speculum should be advanced into the oral cavity (Figure 2-11). The speculum should be continually grasped during the procedure or the cow may swallow the speculum.

A variety of stomach tubes are available. For cattle, a tube should have some flexibility, and the flexibility should be adjustable by temperature so that either warm or cold water can be used to add flexibility or add rigidity, respectively. Tubes that are too soft and flexible will double back during passage, whereas tubes that are completely inflexible risk iatrogenic injury to the pharynx, soft palate, or esophagus. Stomach tubes for adult cattle should have at least ¾-inch outside diameter (1.88 cm) to speed delivery of medications or evacuation of gas (Figure 2-12). Tubes of smaller diameter plug with rumen digesta too easily. Larger tubes, up to the “ultimate tube”—the Kingman—require excellent patient restraint, an appropriate gag or speculum, lubrication of the tube, and appropriate head position of the patient (Figure 2-13).

The increasingly common practice of routine or therapeutic drenching of periparturient and postparturient cattle has led to the widespread use of the McGrath pump (Figure 2-14) on modern dairies. This apparatus has the advantage of only requiring one person to position and then administer the fluids because it is maintained in place by a built-in set of nose tongs. Veterinarians should not hesitate to train laypeople in the proper restraint, positioning, and administration techniques when using this or any other stomach tube/oral drenching device because inadvertent aspiration and drowning are tragic but occasional consequences of their use by unqualified or poorly trained personnel.

DOSE SYRINGE AND DRENCH BOTTLES

Once the cow’s head is restrained, the drench bottle or syringe is introduced into the oral cavity at the commissure of the lips on the same side as the operator. Introduction is facilitated by finger pressure directed on the patient’s hard palate by the operator’s hand that is holding the patient’s head (Figure 2-15). The cow’s muzzle should be held so that the head from pole to muzzle is horizontal to the ground or slightly higher. Holding the head too high or twisting the head to the side interferes with swallowing and risks inhalation of irritating chemicals. Allowances for spillage should be made when calculating the drug volumes to be administered.

ESOPHAGEAL FEEDERS

Popular for delivery of colostrum or electrolyte solutions to newborn or young calves, esophageal feeder devices are potentially dangerous when used by impatient or poorly trained laypeople. Pharyngeal and esophageal lacerations are all too common iatrogenic complications, and inhalation pneumonia is a less common complication. Laypeople should only be allowed to use these devices following training by a veterinarian. Proper disinfection of esophageal feeders that have been used to administer colostrum, milk replacer, or electrolyte solution is an important preventative measure in the control of infectious enteric disease in calves.

NASOGASTRIC INTUBATION

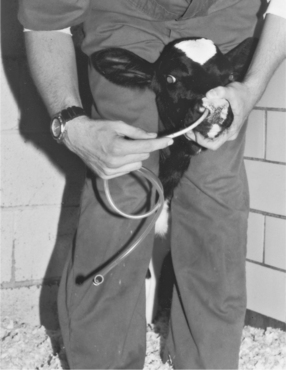

Nasogastric intubation with soft rubber tubing is the preferred method for tube feeding neonatal calves. A soft rubber stallion urinary catheter is passed through the ventral meatus into the esophagus (Figure 2-16). Verification of the tube’s placement within the rumen is made by blowing through the end while ausculting the rumen through the left paralumbar fossa. This technique is easy to perform; easy on the patient; avoids injury to the oral cavity, pharynx, or esophagus by mechanical devices used in oral tubing; and can be done by one person.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR ADMINISTRATION OF ORAL MEDICATIONS

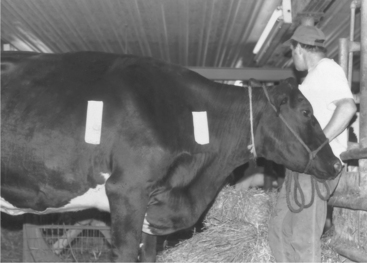

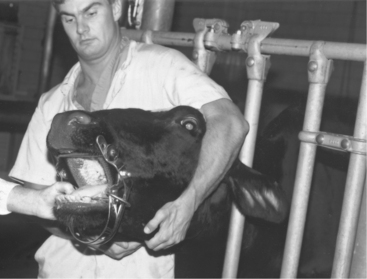

The cow’s head is grasped with the operator’s less adroit hand and the head held tightly to the operator’s body (Figure 2-17). Holding the head tightly allows the operator to move with the cow and also prevents butting injuries that can break human ribs or cause other injuries. The operator is braced by standing with feet placed at least shoulder width apart and with the upper body holding the patient firmly. When a stanchion or head gate is available, the operator also may rest against these objects to further prevent movement.

Once securely positioned, the operator exerts pressure on the patient’s hard palate using the hand that is holding the cow. This gentle pressure causes the patient’s mouth to open and allows medications or devices to be positioned. Common errors to be avoided during oral medication procedures include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree