CHAPTER 14 Nutritional Management of the Starved Horse

METABOLIC RESPONSE TO STARVATION

Starvation and partial starvation are defined as suboptimal nutrient intake severe enough to alter a horse’s health status and performance. The consequences of starvation in horses are muscle weakness; impaired gastrointestinal function, immune response, and wound healing; diarrhea; and hypothermia. Prolonged starvation leads to emaciation, suffering, or death.

EVALUATION OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Physical Examination and Clinical Signs

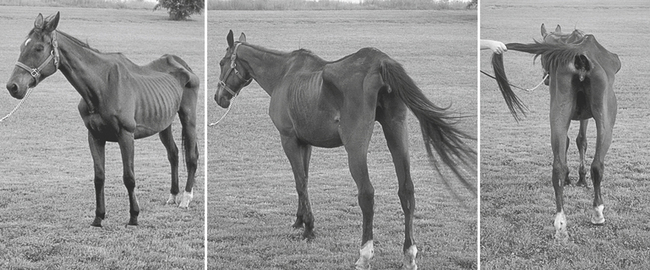

Chronically starved horses have a body condition score ≤ 2/9, lack body fat, have reduced muscle mass and unthrifty hair coat, and may become recumbent (Figure 14-1). Growing horses develop bone and joint deformities and enlarged metaphyses. Horses that have been recumbent for less than 6 hours may remain in a sternal position and alert, make unsuccessful attempts to rise, and eat ravenously when feed is offered. Feces are absent or reduced in volume. Urine may be dark and decreased in volume. Horses that have been recumbent for 12 to 18 hours maintain a good appetite and may attain sternal position, but they have difficulty raising the head and are less alert. After 36 to 48 hours of recumbency, horses are usually in lateral recumbency, cannot raise the head, are stuporous, and may paddle, have seizures, and grind their teeth. Feed placed in the horse’s mouth will prompt attempts to eat. Horses that are recumbent for more than 48 hours are comatose and anorectic. If left untreated, death usually occurs within 72 to 96 hours of the horse’s becoming recumbent.

Laboratory Parameters

Horses deprived of food have progressive anemia, lymphopenia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and high free fatty acids concentration. Hypertriglyceridemia and high free fatty acid concentrations are characteristic findings in the early course of starvation as long as the horse has body-fat stores. Food deprivation causes a rapid increase in serum bilirubin concentration, particularly the unconjugated fraction, with a plateau reached between 64 and 136 hours of starvation. Blood glucose concentration can be normal, low, or high if hypermetabolism develops as a result of concurrent disease. Protein insufficiency causes low blood urea nitrogen concentration that precedes a decrease in serum albumin concentration. Blood urea nitrogen concentration also changes with hepatic and renal dysfunction and dehydration. Hypoalbuminemia may indicate starvation but also develops with losses of albumin through the kidney or digestive tract, decreased synthesis of albumin by the liver, increased albumin escape from the circulation mediated by cytokine release, and dilution of albumin during fluid administration.

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

Increasing the horse’s comfort and maintaining a thermoneutral environment during recovery may improve a starved horse’s chance of survival. A recumbent horse requires assistance in standing and should be supported with a sling (see Chapter 199, Maintenance of Horses in Slings). Dehydration should be corrected by offering fresh water in a series of 2- to 4-L aliquots, 30 minutes apart, to satisfy thirst. Oral electrolyte solutions are beneficial in restoration of extracellular fluid volume but may not be palatable to the horse and should be administered via nasogastric tube. Horses that do not drink voluntarily should be rehydrated with intravenous fluids. Nutritional support should be initiated as soon as possible in all horses with a history of food deprivation and weight loss of 10% or more.

Energy Requirements of a Starved Horse

Predicting the caloric requirements of a starved horse is important because overfeeding may be more harmful than slight underfeeding. With chronic starvation, metabolically active body mass and energy requirement for resting decrease. Therefore, to prevent overfeeding, the initial goal is to feed the horse at its calculated resting energy requirements for the current body weight, keeping in mind that energy requirements will increase during recovery. Acutely starved horses require a sufficient amount of energy to inhibit peripheral lipolysis. However, excessive energy consumption may worsen hepatic triacylglyceride accumulation. Therefore, the safe initial goal for the acutely starved horse is to meet the resting energy requirement for the more optimal body weight. The resting energy requirements are summarized in Box 14-1.