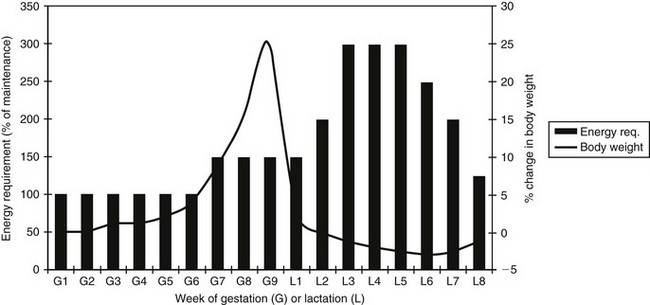

Chapter 210 Successful nutritional management of the dam during pregnancy and lactation takes more than just recommending a particular brand of pet food. Instead, considering the nutrient needs of the individual animal, assessing the qualities of the ration in meeting those needs, and feeding the ration in an appropriate manner are critical elements. The American College of Veterinary Nutrition (ACVN) has developed a graphic representation to help demonstrate these basic principles (Figure 210-1). Figure 210-1 The American College of Veterinary Nutrition Iterative Process of Nutritional Assessment requires consideration of the animal, the ration, and the feeding management. (Courtesy American College of Veterinary Nutrition.) A number of equations are used to determine maintenance energy requirements of the dog, but perhaps the most widely accepted equation provided by the National Research Council (NRC, 2006) is for metabolizable energy (ME) in kilocalories per day: For cats, the equations recommended by NRC (2006) for estimating maintenance energy requirements are similar in format to the dog equation. Cats have less of a range of adult body sizes and are less apt to be highly active or exposed to extreme environmental conditions compared with dogs. Therefore variability in caloric requirements between individuals may be narrower. However, differences in requirements are seen with increasing body condition score (BCS); overweight cats require fewer calories per kilogram (kg) to maintain body weight. To account for this difference, ME can be calculated by two equations, one for “lean” (BCS ≤5 on a scale of 1 to 9) and one for “overweight” (BCS >5): In the bitch the energy requirements for early and midgestation are approximately the same as those for maintenance (Figure 210-2). Although the fetuses are developing rapidly, they remain relatively small. Only in the last few weeks of gestation are additional calories needed for growth of the fetuses and maternal tissues. Depending on the number of fetuses, total weight gain by the time of parturition should be around 15% to 25%. At this time the bitch likely is consuming approximately 150% of her normal maintenance needs. Expressed differently, the increase in energy requirements above maintenance from the fourth week after mating until parturition is approximately 26 kcal of ME per kilogram of body weight per day. Figure 210-2 Energy needs and expected body weight changes of the bitch during gestation and lactation. (Modified from Case LP et al: Canine and feline nutrition, ed 3, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.) The increase in caloric requirements for the queen may not be as dramatic as in the bitch, because the queen still is using energy she stored during early gestation and continues to lose weight during lactation. In the lactating queen, NRC (2006) recommends energy requirements in kilocalories (kcal) per day above maintenance by the following equation:

Nutrition in the Bitch and Queen During Pregnancy and Lactation

Determining Nutrient Requirements

Energy

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree