Chapter 5 Noninfectious Diseases of the Gastrointestinal Tract

DISEASES OF THE FORESTOMACH

Simple Acute Indigestion

Clinical Signs

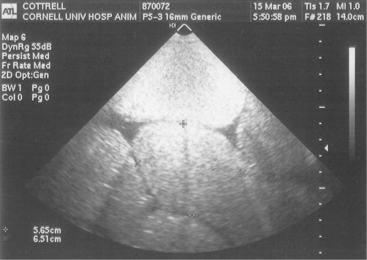

Simple ruminal indigestion results in signs of anorexia, decreased milk production, cold extremities, and rumen dysfunction. Colic is common if there is small intestinal indigestion (Figure 5-1). Although rumen stasis or hypoactivity is typical, some cattle have increased rumen contraction rates but decreased strength of contractions. The cow’s temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rates are often normal with ruminal digestion, but tachycardia and tachypnea may develop in cows especially with small intestinal indigestion associated with colic. Abdominal distention may be present because of mild rumen distention, or gas and fluid distention may be present in the right lower quadrant, representing small intestinal distention. In small intestinal indigestion, enough fluid and gas can accumulate in the small bowel to put severe tension on the mesentery, resulting in signs of colic such as kicking at the belly, bellowing, violent behavior, getting up and down repeatedly, and treading with the hind feet. In fact, this form of indigestion may be the most common cause of true colic in the dairy cow. Colic resulting from small intestinal indigestion can be difficult to differentiate from a mechanical small bowel obstruction. Extremely distended loops of small intestine, fibrin or crepitus on rectal examination, blood in the stool, or deterioration in cardiovascular signs all suggest a physical obstruction rather than simple indigestion. On abdominal ultrasound examination, fluid-filled and dilated loops of small intestine are typical of indigestion and obstruction, with hypomotility being most severe with prolonged physical obstruction and/or strangulation (Figure 5-2). The fluid responsible for small bowel distention results from stasis associated with indigestion and quickly appears as diarrhea as the cow responds to therapy or self-initiates gastrointestinal activity. Potential lameness sequelae including laminitis, sole ulcers, and toe abscesses may be observed in some cases 2 to 6 weeks after a rumen indigestion episode.

Moderate to Severe Acute Ruminal Indigestion

Clinical Signs

Signs of moderate to severe indigestion include a dramatic decrease in appetite and milk production, complete gastrointestinal stasis, cool peripheral parts, normal or subnormal rectal temperature, and normal or elevated heart and respiratory rates. Some affected cows are hypocalcemic enough to be recumbent and unable to rise. It should be emphasized that these cows have more severe signs than simple indigestion cases, including splashy rumen, dehydration, and tachycardia. As with any form of indigestion, clinical signs of lameness (laminitis) may occur 2 to 6 weeks later.

Fulminant Acute Lactic Rumen Acidosis

Clinical Signs

Affected cattle are completely off feed, exhibit drastically decreased milk production, are dehydrated, and have elevated heart (90 to 120 beats/min) and respiratory rates (50 to 80 breaths/min). They typically have a splashy, totally static rumen, cool skin surface, subnormal temperature, and diarrhea or loose manure. Affected animals are weak and can be recumbent (Figure 5-3). Because of dehydration, titration of bicarbonate, hypotension, and high levels of lactic acid in the rumen and the blood, severely affected cattle have metabolic acidosis.

Ancillary Data and Diagnosis

Diagnosis of lactic acidosis is made by combining clinical signs with a detailed history of feeding in the herd. In acute cases, obtaining a rumen fluid sample through a stomach tube, percutaneous left flank puncture, or at necropsy examination of acute fatalities will reveal a rumen pH of 4.5 to 5.0. It must be emphasized that cattle with lactic acidosis that survive for 24 hours or more often have rumen pH values that increase to 6.5 to 7.0 because of the buffering effects of swallowed saliva and plasma dilution of the rumen contents. Other laboratory aids include acid-base and electrolyte values that tend to reflect a metabolic acidosis, a neutropenia with left shift in the hemogram, and marked azotemia. This is true even for fatal cases that survive 24 hours or more after ingestion of toxic quantities of grain. The systemic acidosis and acidemia are the result of increases in both D and L lactic acid. In some cases, the diarrhea or loose manure that is passed contains whole particles of the causative concentrate and may represent a clinical diagnostic clue.

Treatment

Other treatments may be attempted for animals showing less severe signs and higher rumen pH values or when the number of animals affected precludes rumenotomies. One method involves passing a large-diameter stomach tube or Kingman tube and lavaging the rumen with warm water several times with the aid of a bilge pump. Several flushes with 10 to 20 gallons of water are necessary, and return flow of fluid must be effective for this treatment to be successful. Following lavage, antacid solutions such as 2 to 4 quarts of milk of magnesia, activated charcoal, and ruminotorics are administered, as well as supportive calcium solutions and IV fluids as indicated. Affected cattle should not be allowed to engorge on water because their atonic rumens will only distend again. Once rumen activity returns, free choice water may be made available. Another option that has been used successfully is to simply drain as much rumen fluid (Figure 5-4) as possible and administer 1 to 2 lb of activated charcoal into the rumen. This appears to be effective in binding rumen toxins (e.g., endotoxin). Additionally, affected cattle should receive SQ administered calcium solutions and IV administered isotonic fluids. Cows with moderate to severe rumenitis are generally treated with penicillin (10,000 to 20,000 IU/kg administered intramuscularly [IM] or SQ) in an effort to prevent bacteremia and liver abscess formation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should not be used because these may predispose to fungal overgrowth.

Other treatments are empiric. They include antihistamines, penicillin solutions administered via a stomach tube in an effort to reduce the numbers of S. bovis organisms in the rumen, and roughage-only diets until the animals recover.

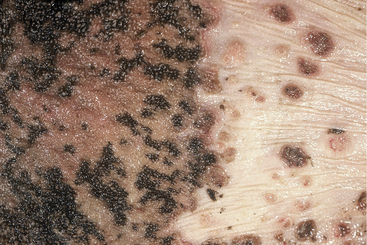

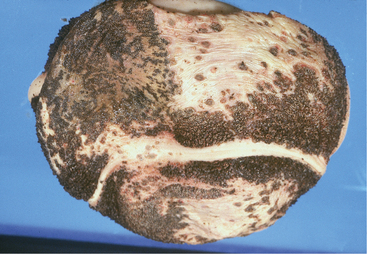

Cattle affected with lactic acidosis that survive the acute phase and have their rumen pH return to normal still are at risk for sequelae to the chemical rumenitis that has occurred. During the next several days, bacterial opportunists such as Fusobacterium necrophorum may invade the areas of chemical damage, attach to the rumen wall, and cause a bacterial rumenitis (Figure 5-5). If the animal lives 4 to 7 days or has been treated heavily with antibiotics or steroids, a mycotic rumenitis may occur in these previously damaged areas (Figure 5-6). Bacterial and mycotic opportunists invade the damaged rumen mucosa, ascend the portal circulation, and cause embolic infection of the liver, lungs, and other organs, resulting in fever and, in severe cases, death (Figures 5-7 and 5-8). Fever resulting from mycotic infection generally is unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Embolic infections of the brain may cause bizarre neurologic signs 7 to 14 days following the original clinical signs of lactic acidosis.

Figure 5-5 Chemical and bacterial destruction of the entire omasal mucosa as a result of lactic acidosis.

Subacute to Chronic Rumen Acidosis

This syndrome, also called subclinical ruminal acidosis (SARA), occurs more commonly in lactating cows than the previously discussed acute clinical syndromes of indigestion and/or ruminal acidosis and derives from modern feeding practices. In brief, feeding rapidly fermentable concentrates and highly acid feeds allows a degree of rumen acidosis for a transient period after ingestion. During this period of acidosis, small areas of rumen mucosa are damaged by the same chemical mechanism that causes more widespread lesions in lactic acid indigestion. These small areas of rumenitis may act as entry points for opportunistic bacteria that subsequently ascend the portal circulation and result in liver abscesses. These may be single or multiple and, when located near the hilus of the liver, predispose the cow to caudal vena caval thrombosis syndrome. Dairy cattle seldom develop the “sawdust liver” or miliary liver abscesses of feeder beef animals despite the similar pathophysiology.

Ruminal Bloat

Bloat can be defined as obvious ruminal enlargement resulting in left-sided abdominal distention in both dorsal and ventral quadrants (Figure 5-9, A and B). When severe, bloat may cause generalized distention resulting from ventral sac enlargement into the right lower quadrant and crowding of the remaining abdominal viscera into the right dorsal quadrant. Causes of bloat may be divided into acute and chronic etiologies.

Acute Bloat

Etiology

Acute bloat can be classified into at least three categories determined by the physical properties causing the bloat:

Clinical Signs

Free-gas bloat causes a large gas ping on the left upper abdomen extending to the dorsal midline (Figure 5-10). In some cattle with free-gas bloat, an obvious ping may not be present. If a stomach tube can be passed easily and relieves the bloat, free-gas bloat is confirmed. Other physical signs and signalment data may allow a specific diagnosis of the cause of the bloat. For example, hypocalcemia may be considered if the cow is periparturient and shows signs of normal or subnormal temperature, cool peripheral parts, slow pupillary responses to direct light, recumbency, or weakness. Indigestion with tympany may cause few signs other than free-gas bloat, and signs other than free-gas bloat or signs referable to hypocalcemia mean other diseases must be ruled out. Animals with esophageal obstruction (choke), esophageal injury, or pharyngeal injury with perforation usually present with excessive salivation, an anxious expression, extended head and neck, bloat, and fever. Passage of a stomach tube would be impeded by a choke and be resisted by a cow with pharyngeal or esophageal injury. Frothy bloat is diagnosed based on the typical left-sided distention, less obvious pinging when simultaneous percussion and auscultation are performed, and failure to relieve the distention on passage of a stomach tube. The bloat may progress rapidly if it is frothy bloat, eventually distending both sides of the abdomen to its maximal limits (Figure 5-11) and causing respiratory distress, hypoxemia, poor venous return of blood to the heart, hypotension, and death.

Treatment

In cases of acute frothy bloat, passage of a stomach tube seldom produces dramatic relief of the rumen distention but does aid in diagnosis and allows treatment with surfactant agents such as Therabloat (poloxalene drench concentrate; SmithKline Beecham Animal Health, West Chester, PA) or vegetable oil to break down the froth. In some frothy bloats, a Kingman stomach tube may permit decompression, but this is not the rule, and in severe cases with thoracic compression, passage of the tube may, on rare occasion, cause acute death. Oral ruminotorics-laxative-antacid powders in warm water and parenteral calcium solutions also should be administered to encourage rumen emptying. Emergency rumenotomy (Figure 5-12) is the treatment of choice for progressive and severe frothy bloat. In a hospital environment, hypertonic saline administration, intranasal oxygen, and analgesics (flunixin) are helpful in stabilizing the cow during standing surgery.

Prevention of acute bloat is possible only when managerial changes have allowed ingestion of causative feedstuffs, including sudden availability to lush alfalfa pastures. Fortunately most dairy farmers are aware of these dangers, and it seldom is necessary to educate owners concerning such hazards and appropriate preventative measures such as gradual introduction to succulent pasture, prefeeding with long-stem hay, pasture surfactant sprays, poloxalene salt blocks, or simple avoidance.

Chronic Bloat

Etiology

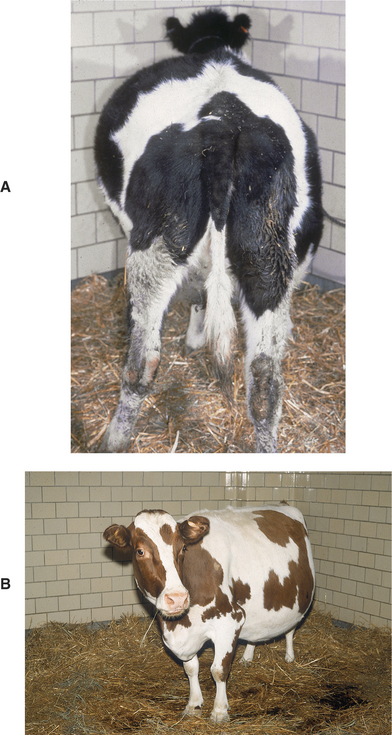

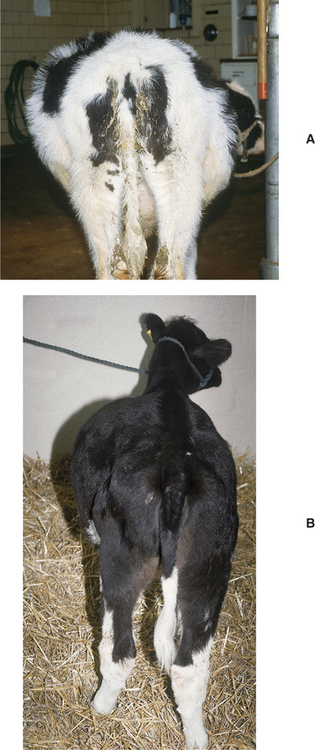

In calves, most cases of chronic bloat have a dietary or developmental etiology. Low fiber diets are the usual cause in calves fed only milk or milk replacers (Figure 5-13, A and B). Otherwise, these affected calves are healthy except for the free-gas bloat that develops shortly after eating. Calves that have been overtreated with oral antibiotics for systemic infections or diarrhea also may develop bloat associated with abnormal rumen flora. Calves affected with diarrhea and treated with methscopolamine or other parasympatholytic drugs may develop a paralytic ileus and subsequent bloat that persists for 24 to 72 hours after the administration of the drug. Although overdosage may have occurred, some calves develop bloat even after using the manufacturer’s recommended dosages of methscopolamine.

Calves that have suffered severe bronchopneumonia occasionally develop free-gas bloat from damage to the thoracic portion of the vagal nerve or enlarged thoracic lymph nodes that cause failure of eructation. Left displacement of the abomasum (LDA) in calves may cause chronic or intermittent free-gas bloat, thereby confounding a diagnosis of LDA. Intermittent or chronic bloat associated with unthriftiness, inappetence, claylike feces, and abdominal distention occasionally occurs in 3- to 8-week-old dairy calves fed milk (mostly by bucket rather than bottle) (Figure 5-14, A). These calves are called “ruminal drinkers” because they have failure of the reticular groove reflex, thus causing milk to flow directly into the rumen rather than the abomasum. Ruminal parakeratosis and hyperkeratosis result in addition to metabolic and endocrine abnormalities. The calves may have excessive intestinal production of both D and L lactic acid and become severely acidotic from the D-lactic acid. The bloat may occur acutely within 1 hour after feeding but may also become chronic, and in some cases there may be enough milk putrefaction to cause the calf to become quite ill. Passage of a stomach tube may cause reflux of a gray fetid fluid (Figure 5-14, B).

Older calves that have been weaned off milk or milk replacers also may develop chronic free-gas bloat of dietary origin if fed a low fiber diet. Although this can occur on silage and grain diets, it is much more common in calves fed all-pelleted rations. Up to 10% or more of calves fed all-pelleted rations with no hay supplementation will develop chronic bloat that worsens shortly after they ingest pellets and then drink large quantities of water. Many other causes of chronic bloat also exist in postweaning calves but are more difficult to diagnose and treat. These include inherent tendencies of bloat as seen in dwarf animals and inherent defects in forestomach innervation or smooth muscle function. Other lesions such as abdominal abscess, umbilical or urachal adhesion, intestinal obstruction, LDA, focal peritonitis, and rarely abomasal impaction (Figure 5-15) may lead to chronic bloat as well.

Figure 5-15 Abdominal distention characteristic of vagus indigestion in a calf with abomasal impaction.

Esophageal lesions also must be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic bloat in the calf. These include pharyngeal and esophageal trauma induced by balling guns, stomach tubes, or esophageal feeders. These lesions may damage the intricate vagal nerve branches responsible for eructation, swallowing, and forestomach motility. Esophageal motility disorders, although rare, should be considered as a cause of bloat in calves with a dilated esophagus. Thymic lymphosarcoma and enlarged mediastinal or pharyngeal lymph nodes resulting from the juvenile form of lymphosarcoma are the most common neoplastic causes of chronic bloat in calves. Diaphragmatic hernias are rare in dairy cattle but can result in acute or chronic rumen distention and bloat (Figure 5-16). Generally the reticulum is entrapped in the chest through the diaphragmatic rent. Signs include decreased cardiac and lung sounds and dullness during percussion in the ventral thorax (unilateral or bilateral), abdominal distention, bloat, vomiting, and dyspnea. Diaphragmatic hernias may be congenital or acquired as a result of trauma, parturition, or progressive weakening of the diaphragm adjacent to a hardware perforation and reticuloperitonitis.

Specific treatment depends on the specific cause of the chronic bloat. Because a portion of these cases involve lesions affecting the vagal nerve branches, treatment is discussed under Vagal Indigestion. Calves with unexplained chronic and/or intermittent free-gas bloat are best treated by making a temporary rumen fistula (Figure 5-17). Calves with chronic or intermittent bloat and ill thrift because of ruminal drinking of milk can be weaned or fed via a bottle rather than a bucket. If they become acutely ill in association with feeding milk and bloat, an oral-rumen tube should be passed to drain as much fluid as possible from the rumen, and the calf should be treated with systemic antibiotics and fluids.

Traumatic Reticuloperitonitis (Hardware Disease)

Signs

Once a metallic foreign body perforates the reticular wall, clinical signs develop. These signs are extremely variable and influenced by the anatomic region of perforation within the reticulum, depth of perforation, associated abdominal or thoracic viscera injury by the perforating object, physical features of the causative object, and the affected cow’s stage of gestation or lactation.

Classic hardware disease causing acute localized reticuloperitonitis results in a sudden, dramatic, and often complete anorexia and cessation of milk production. Milk production may decrease to near zero within 12 hours and prompt the owner to seek veterinary attention for the cow. Affected cattle may have fever (103.0 to 105.0° F/39.44 to 40.56° C), normal to mildly elevated heart and respiratory rates, abducted elbows, an anxious expression, an arched stance (Figure 5-18), hypomotile rumen with or without mild tympany, scant dry feces, and abdominal pain localized in the cranial ventral abdomen near the xiphoid. When examined within 24 hours of onset, classic cases as described are relatively easy to diagnose. Many clinical cases show more variable signs (e.g., some cows stand up more than normal, whereas others lie down more than normal) and represent more difficult diagnostic challenges. In some cases, vague signs of partial anorexia, decreased milk production, and changing fecal consistency may be observed by the owner and may have been present for some time before veterinary attention is sought. Physical examination may reveal little beyond ruminal hypomotility or mild tympany suggestive of localized peritonitis, and cranial abdominal pain. In some mild cases, careful auscultation and observation may reveal treading with the hind feet because of the pain associated with localized peritonitis during ruminoreticular contraction. Affected cattle with less obvious signs may “grunt” or grind their teeth while being “poked” by a metallic foreign body embedded in the reticular mucosa or submucosa, or one that has penetrated full thickness and continues to cause pain intermittently. Occasionally cattle affected with hardware disease will “vomit” or regurgitate more material than they can retain as a cud. This represents a neurogenic or pressure-related triggering of the regurgitation reflex from reticular irritation. In these less obvious cases, careful physical examination and attention to detail when assessing abdominal pain are important keys to thediagnosis.

Ancillary Data and Procedures

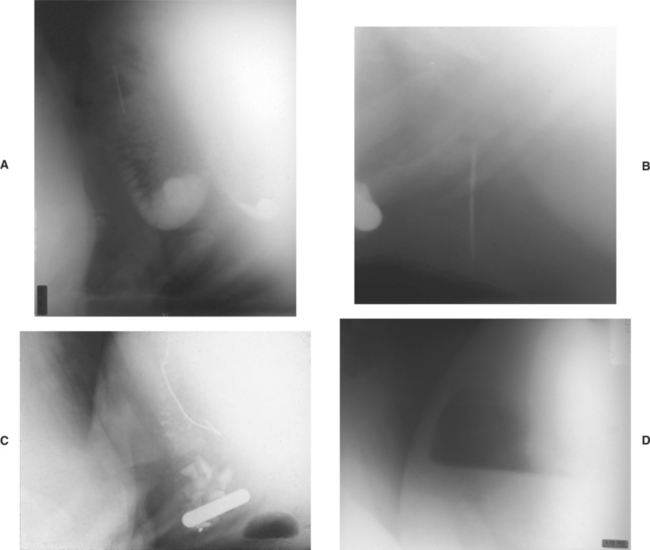

Laboratory tests may be helpful in diagnosing confusing cases. Peritoneal fluid containing elevated total solids and white blood cell numbers supports a diagnosis of peritonitis. A complete blood count (CBC) may or may not be helpful because many patients with hardware disease have normal CBCs, although almost all have elevated plasma fibrinogen levels. Some patients with hardware disease with acute localized peritonitis and most patients with acute diffuse peritonitis will show a degenerative left shift in the leukogram. In chronic (longer than 10 days) hardware disease, serum globulin is often elevated (.5.7 mg/dl), and the leukogram may be normal or confirm mature neutrophilia. Cows with peracute, diffuse septic peritonitis caused by hardware disease may have hypoproteinemia as a result of fluid and protein loss into the peritoneal cavity, but this does not occur as commonly as with abomasal perforation. Because of forestomach and abomasal hypomotility or stasis, patients with hardware disease have a hypochloremic, hypokalemic, metabolic alkalosis that varies in severity in direct proportion to the degree of stasis. Cattle affected with subacute or chronic hardware disease that has caused complete rumen stasis may have a profound metabolic alkalosis with serum chloride values in the 40 to 50 mEq/L range. It is debatable whether alkalosis of this magnitude totally results from the disease present or is accentuated by oral administration of ruminotoric laxative medications before blood collection. Regardless of pathophysiology for alkalosis of this magnitude, the prognosis is not hopeless. The most helpful ancillary tests are abdominal ultrasonography and reticular radiography. Abdominal ultrasound should reveal an abnormal pocket of fluid and fibrin in the anterior abdomen (Figure 5-19). Radiography is the best test for confirming metallic penetration of the reticulum (or rarely rumen), the current location of the metal object, and the presence and size of perireticular abscesses (Figure 5-20, A to D). Unfortunately, this is the least available test for the practicing veterinarian because extremely powerful radiographic equipment is necessary to penetrate the reticular region in adult cattle.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of traumatic reticuloperitonitis is based primarily on physical examination and is aided by laboratory work in less obvious cases. In cattle with obvious signs of peritonitis, perforating abomasal ulcers are the chief differential consideration. Perforating abomasal ulcers tend to cause pain in the midventral abdomen on the right side of midline, are usually associated with fever, and are most common 2 weeks before freshening and up to 100 days postpartum. Acute pyelonephritis or necrotic lesions of the cervix or vagina may present similar to hardware. With pyelonephritis, the urine may be discolored and rectal examination reveals an enlarged ureter. Cows with necrotic cervicitis or vaginitis are often febrile, depressed, stand either hunched up or stretched out, and have rumen atony, but unlike hardware cases, they strain and frequently aspirate air in the rectum. If an active magnet is already present in a cow having signs of peritonitis, abomasal ulceration is more likely than hardware disease. A compass can be used during physical examination to detect an active magnet in the reticulum. The compass is moved slowly into position behind the elbow on the left thoracic wall. A 60- to 90-degree deflection indicates the presence of a strong magnet in the reticulum. In cows with normal rectal temperatures, hardware disease must be differentiated from indigestion and ketosis. This can be done based on the absence of abdominal pain in patients with ketosis, while cows with hardware have evidence of abdominal pain in addition to ruminal hypomotility and negative to trace urinary ketones. A cow affected with musculoskeletal diseases such as polyarthritis, laminitis, back pain, or trauma could be confused with one having hardware disease because of an arched stance, weight loss, anorexia, and decreased production. Physical examination should differentiate these diagnoses, however.

Treatment

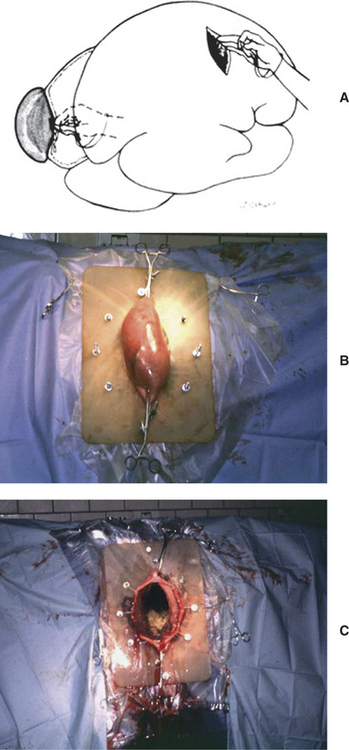

Except for valuable cows, conservative treatment is indicated in most acute cases of traumatic reticuloperitonitis. This treatment consists of a magnet administered orally, systemic antibiotics to control existing peritonitis, and stall rest to aid in the formation of adhesions; other symptomatic therapy such as oral fluids, ruminotorics, calcium solutions, and oral electrolytes also may be helpful. If dehydration is present and metabolic alkalosis is suspected or confirmed, fluid therapy and supplementation with potassium chloride orally (1 to 2 oz orally, twice daily) or IV are indicated. In severely alkalotic patients, alkalinizing ruminotorics should be avoided. Conservative therapy results should be evaluated within 48 to 72 hours. If the affected cow is beginning to eat and ruminate and production begins to increase, recovery can be anticipated. If the cow is not improving or if appetite and rumen activity wax and wane, rumenotomy may be indicated. Following oral administration of a magnet, the magnet first drops into the rumen. The magnet only moves to the desired location in the reticulum through effectual ruminoreticular contractions. Therefore if the rumen remains static, it is unlikely the magnet will move into the reticulum to grasp and hold the foreign body. It is revealing to note the number of cattle that are referred to teaching hospitals that possess a magnet or magnets within the rumen rather than the reticulum when the magnet has been administered as a therapeutic rather than prophylactic aid. If the affected cow already has a magnet at the time signs develop, exploratory laparotomy and rumenotomy may be indicated initially rather than conservative therapy. This situation may occur when the foreign body is extremely long (.15 cm) and extends off the magnet to a dangerous level or is not attached to a magnet, as in the case of an aluminum needle. Rumenotomy and object removal should be performed immediately in valuable cows to limit further movement of the object and worsening peritonitis. When laparotomy and rumenotomy are elected, it is best not to explore the serosal surface of the rumen and reticulum if adhesions are obvious. This will avoid dissemination of the peritonitis. During rumenotomy, a careful palpation of the entire reticulum is indicated to find the offending foreign body, which may remain only partially in the reticular wall. Left-sided laparotomy and rumenotomy allow for confirmation of the diagnosis, removal of the foreign body/bodies, and drainage of reticular abscesses into the lumen (Figure 5-21, A to C). Even with radiographic and/or ultrasonographic guidance, it can be challenging to identify and remove some foreign bodies that are embedded within mature, chronic, fibrous adhesions, and reaching a comfort level with abscess drainage by sharp scalpel incision into the reticular wall at the site of the adhesions takes some practice and experience. If there is a large reticular abscess, it could be drained via a ventral percutaneous approach, although cellulitis, reticular fistula, and dissemination of the peritonitis may occur.

Sequelae

Cattle suffering from hardware disease may have myriad complications secondary to perforation and peritonitis. Septic pericarditis is perhaps the best-known complication and occurs when the metallic foreign body perforates in a cranial direction, perforating the diaphragm and pericardium (Figure 5-22, A and B). Reticular abscesses also are fairly common sequelae and often occur on the cranial or right wall of the reticulum where they directly, or indirectly, cause dysfunction of the ventral vagus nerve branches and result in signs of vagus indigestion. Signs of vagus indigestion vary from mild ruminoreticular disturbances to omasal transport difficulties or abomasal dysfunction/impaction. Septic pleuritis, pneumonia, thoracic abscesses, diaphragmatic hernias, and traumatic endocarditis are less frequent complications of a perforation of the diaphragm. Occasionally a metallic foreign body—usually a wire—associated with a ventral perforation migrates through the sternum or cranial ventral abdomen, resulting in a reticular fistula (Figure 5-23). Any perforation of the right wall of the reticulum may directly or indirectly, through associated inflammation and adhesions, injure, inflame, or irritate the ventral vagus nerve branches and result in signs of vagus indigestion. Therefore when hardware disease is suspected as the cause of vagus indigestion, a meticulous search of the right wall of the reticular mucosa is indicated during rumenotomy.

Prevention

All breeding age heifers or heifers 1 year of age, as well as young bulls, should receive strong prophylactic magnets. Not to recommend this for valuable cattle represents negligence, and the loss of a single valuable dairy cow because of traumatic reticuloperitonitis is inexcusable. Unfortunately hardware disease is still extremely common, and many cows die each year because the owner “forgot” to administer a magnet. Although occasional cows pass magnets through the gastrointestinal tract and some magnets do lose strength, the magnet remains the major means of preventing this disease. The effectiveness of magnets is apparent at slaughterhouses, where an impressive array of metallic foreign bodies are found trapped tightly to magnets. When purchasing magnets, the owner or veterinarian should assess the strength of the magnet by testing it against metallic objects. Inferior magnets should not be purchased.

Diseases Affecting the Vagus Innervation of the Forestomach and Abomasum—Vagus Indigestion

Signs

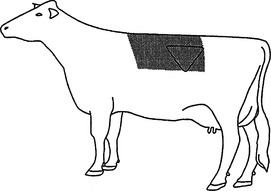

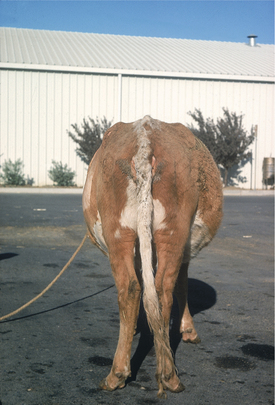

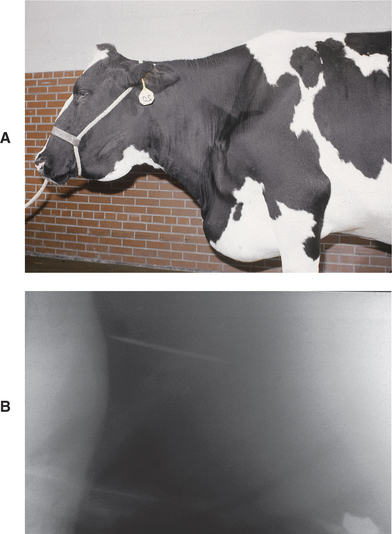

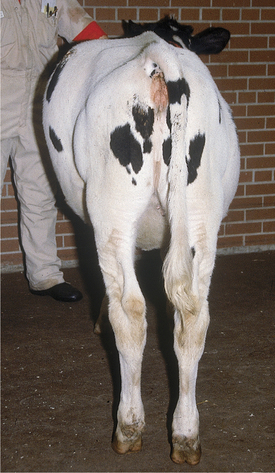

The abdominal distention that develops is classical, with distention in the upper left, lower left, and lower right quadrants as the cow is viewed from the rear (Figure 5-24). In most cases, this distention results from progressive ruminal enlargement with the ventral sac enlarging toward the right. Therefore this typical distention results in an L-shaped rumen, as viewed from the rear or palpated per rectum. In severe cases, the rumen ventral sac not only fills the entire right lower quadrant of the abdomen but also may expand into the right upper quadrant so the rumen assumes a V shape. Extreme distention of the rumen into a V shape occasionally traps gas in the most dorsal region of the now expanded ventral sac, and this gas may result in an area of tympanitic resonance in the right upper quadrant. In very rare instances of true abomasal impaction or pyloric stenosis, the abomasum may be large enough to account for this right lower quadrant distention.

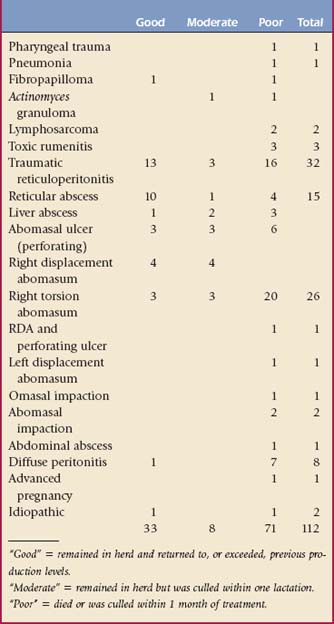

Depending on the primary lesions, signs of vagus nerve dysfunction may appear acutely or have a delayed onset. In most cases, onset of signs and typical abdominal distention occur several days to weeks after the affected cow initially developed signs of illness. Some primary lesions are relatively easy to diagnose, whereas others require extensive ancillary data or exploratory surgery. In all cases, primary lesions resulting in the syndrome of vagus indigestion should be sought because prognosis directly depends on the primary cause. Having discussed the general signs of vagus indigestion, specific primary causes will next be discussed, and individual signs referable to each will be included when pertinent. Table 5-1 summarizes the clinical results of long-term follow-up evaluation for 112 cases of vagus indigestion and illustrates relative occurrence of the various primary lesions.

Neoplasms such as thymic, juvenile, or adult lymphosarcoma, neurofibromatosis, and pulmonary carcinomas sometimes may result in signs of vagus indigestion resulting from extraluminal compression of the esophagus or pressure on the vagus nerve and subsequent failure of eructation with chronic free-gas bloat.

Most lesions involving the reticulum are located on the right or medial wall of the reticulum. These lesions damage the ventral vagal nerve branches with inflammation, pressure, or direct trauma. Traumatic reticuloperitonitis, reticular abscesses, liver abscesses, severe toxic rumenitis, and neoplasms such as lymphosarcoma would be included in this group. Some authors include adhesions of the cranial and medial reticulum in this category and imply that mechanical dysfunction results from these adhesions. Most authors, however, believe that neurogenic damage to the ventral vagal branches must occur even if adhesions are present. In this category, prognosis seems to vary depending on the cause. Traumatic reticuloperitonitis carries a variable prognosis based on the degree of peritonitis and involvement of the ventral vagal branches (13 of 32 cases had good outcomes), whereas reticular abscesses carry a more favorable prognosis (10 of 15 cases had good outcomes) (see Table 5-1) presumably because they tend to cause vagal nerve dysfunction by pressure on the nerve. This pressure dysfunction is alleviated by surgical drainage.

Lesions of the forestomach distal to the reticulum or involving the abomasum include a diverse group of problems such as lymphosarcoma (see video clip 10) and other neoplasms, diffuse peritonitis, peritonitis caused by perforating abomasal ulcers, abdominal abscesses, vagal nerve damage and possible vascular thrombosis secondary to right-sided AV, omasal impaction, and chronic or severe abomasal impaction. In general, prognosis is poor for cattle with signs of vagal indigestion secondary to these lesions (see Table 5-1) because of the extent of the pathology, the possibility of multiple sites being affected, and the likelihood of functional and mechanical outflow disturbances. In referral practice, a disproportionate number of cattle with right-sided AV are treated. Many of these cattle have been affected for 24 hours or more before referral, thereby being at high risk for subsequent signs of vagal nerve dysfunction. Usually these cattle appear to improve for 24 to 72 hours after surgical correction of their AV but then begin to show signs of an outflow disturbance. These cattle then develop bradycardia, typical ruminal distention, scant manure, poor appetite, and abdominal distention typical of an L-shaped rumen.

Most distention involves the forestomach compartments even though the abomasum was the primary problem. Recent work helps explain this syndrome. Because volvulus involves the abomasum, omasum, and reticulum, either neurogenic damage by stretching the ventral vagal branches or thrombosis of major vessels supplying the lesser curvature of the abomasum, omasum, and reticulum may result from prolonged volvulus. Most cattle that develop signs of vagal indigestion following right-sided DA and volvulus never recover despite attempts at therapy. Rumenotomy is seldom suggested for cows with vagus indigestion secondary to right-sided volvulus of the abomasum because the primary pathology is thought to be irreversible. Vagal nerve damage secondary to right-sided volvulus has an extremely poor prognosis with only 3 of 26 patients having a good outcome (see Table 5-1). Right-sided DAs and volvulus should be corrected on an emergency basis to minimize chances of vagal nerve damage or outflow disturbance. Valuable cattle that begin to develop symptoms of vagus indigestion following correction of right-sided volvulus of the abomasum by omentopexy may be considered for abomasopexy or abomasopexy following rumenotomy to ensure proper abomasal alignment that may improve outflow. The prognosis, however, remains guarded to poor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree