Chapter 7 New Zealand White rabbit

Introduction

Rabbits are classified in the order Lagomorpha. They differ from rodents in that they possess an additional pair of incisor teeth directly behind the large incisors of the upper jaw. There are over 100 different breeds of rabbit that are descendants of the European wild rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus. New Zealand White rabbits are used extensively in toxicological studies; however, the design of the majority of study protocols are such that full histopathology of all organ systems seldom occurs. The animals in toxicology studies are euthanized at the end of the study period whilst still relatively young and so pre-neoplastic and neoplastic diseases are rarely seen. The range and extent of neoplastic and hyperplastic lesions that occur in older rabbits have been well described in the standard veterinary medicine and pathology texts on laboratory animals (Hrapkiewicz et al 1998, Percy & Barthold 2007, Saunders & Rees-Davies 2005). This chapter will focus on lesions encountered as spontaneous background findings in young rabbits which are between six and 24 months old.

Cardiovascular system

The chambers of the right side of the rabbit heart are thin and the right ventricle often contains clotted blood with no evidence of contraction (Percy & Barthold 2007). The rabbit right atrioventricular valve is bicuspid rather than tricuspid.

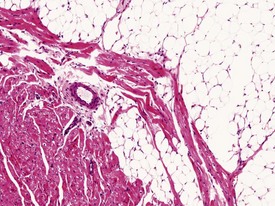

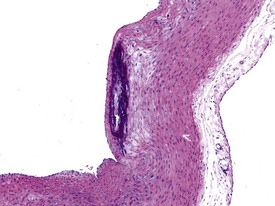

Occasionally evidence of the closure of the ductus arteriosus may be seen as foci of mineralization in the media of major vessels of young rabbits in toxicology studies, depending on the plane of section. Mononuclear inflammatory-cell infiltrates are recorded infrequently in the myocardium (Lehr 1965). The foci are usually at the base of the interventricular septum. These are inert cellular infiltrates with no accompanying myocardial necrosis or fibrosis associated with the lesion. Other findings recorded regularly at a low incidence in the rabbit heart include mineralization of the left atrial appendage, pericardial lipomatosis (Fig. 7.1) and pericardial fibrosis. Calcification of the aorta and large veins (Fig. 7.2) (arteriosclerosis) may be seen at necropsy in older animals (e.g. ex-breeding colonies). Foci of myofibre degeneration and fibrosis with a mononuclear-cell infiltrate in the heart may be associated with administration of ketamine/xylazine combinations or detomidine in Dutch Belted rabbits (Percy & Barthold 2007).

The Watanabe rabbit is used extensively as an animal model of natural endogenous atherosclerosis (Garibaldi & Pecquet 1988). Atherosclerosis may also be observed in the aorta of rabbits (Salamon et al 2007).

Hemolymphoreticular system

In the rabbit polychromasia of the erythrocytes is a normal finding. Heterophils are the counterpart of the neutrophil and have distinct acidophilic granules. Hyposegmented neutrophils may be observed in a rabbit blood smear. This is known as the Pelger–Huet syndrome, and this anomaly is inherited as a partial dominant trait in rabbits (Salamon et al 2007). Basophils in the rabbit may be relatively numerous and occasionally represent up to 30% of circulating leukocytes (Percy & Barthold 2007).

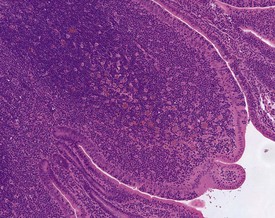

Large eosinophilic histiocytes are commonly seen within the thymus, lymph nodes and follicles of the epithelium-associated lymphoid tissue (e.g. bronchiolar and gut-associated lymphoid tissue) (Fig. 7.3). These histiocytes may have particulate debris in the cytoplasmic vacuoles. In the thymus they are usually situated in the medullary area of the peripheral lobules. Other findings recorded regularly at a low incidence in the hematopoietic tissues of rabbits include: ectopic parathyroid in the thymus, increased extramedullary haematopoiesis in the accessory spleen (Weisbroth et al 1976), erythrophagocytosis, sinusoidal dilation, and pigmented macrophages in the lymph nodes. In addition, lymphocyte infiltrations may be noted in the liver, heart and lungs (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Respiratory system

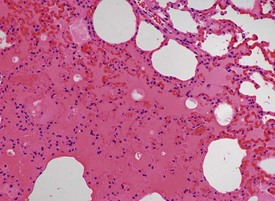

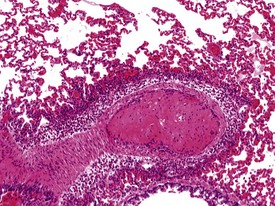

The submucosa of the nasal cavity contains individual or small aggregates of lymphocytes, but no lymphoid follicles are present. There are no respiratory bronchioles in rabbits. Alveolar macrophage accumulations are often seen in the lungs. The alveolar macrophage aggregates have no particular distribution pattern and can be peripherally placed just beneath the pleura, or at the bronchoalveolar junction. The macrophages are hypertrophic with pale pink cytoplasm, but usually there is no associated inflammatory cell response. Other findings recorded regularly in the rabbit lung include: perivascular mononuclear or eosinophilic inflammatory cell infiltrations, ectopic bone and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) hyperplasia in older rabbits. Submucosal mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrations are seen occasionally in the trachea and larynx. Barbiturate euthanasia can result in petechiae on the surface of the lung which disappear during processing (Salamon et al 2007). In addition, the process of euthanasia may cause alveolar oedema and congestion in the rabbit lung (Fig. 7.4). Occasional thrombi with arteritis and periarteritis may be noted in the rabbit lung (Fig. 7.5).

Gastrointestinal system

Malocclusion of the teeth is reasonably common in rabbits due to congenital mandibular prognathia or secondary to inadequate wear. Ulcerations of the tongue may be caused by lower molar malocclusion. Upper molar malocclusion causes buccal ulcerations of the cheek. Malocclusion of teeth is controlled in contract research organizations or pharmaceutical industries by the clipping of overgrown incisors. A large pair of circumvallate papillae on the dorsal surface of the tongue are occasionally mistaken for papillomatous growths. Vomiting is not possible in the rabbit, and food and cecal pellets are always present in the stomach. Hairballs or trichobezoars in the stomach or pylorus are encountered commonly, but are generally incidental findings at necropsy (Haugh 1987). The hairballs are masses of hair and ingesta that result from excessive self-grooming and boredom (Percy & Barthold 2007). Predisposing factors to hairball formation may include low-fibre diets, experimental manipulation and stress. Heterophils and lymphocytes are common in the submucosal area of the stomach. In contrast to other laboratory animals, Brunner’s glands are present throughout the length of the rabbit duodenum (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Rabbits are hindgut fermenters with a large and complex digestive system. They practise cecotrophy, which is the ingestion of mucus-coated night faeces. Cecotrophy is controlled by the adrenal glands and may be altered during periods of stress. The large intestines consist of a spiral cecum, a sacculated colon and the rectum. The sacculus rotundus is a round, thick-walled enlargement at the ileocecal junction (Percy & Barthold 2007). At the ileocecal junction adjacent to the sacculus rotundus, the cecum has a large mass of lymphoid tissue called the cecal tonsil. This may be referred to as the ileocecal tonsil, or ampulla ilei in older anatomy texts. The walls of this area are thickened by aggregations of organized lymphoid tissue and macrophages and this area should not to be mistaken for lymphoid hyperplasia or increased cellularity. The grossly thickened walls of the sacculus rotundus, caecal tonsil and vermiform appendix are due to aggregates of lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria and submucosa. At the junction between the transverse and descending colon is the fusus coli, which is unique to rabbits and is made up of ganglion cells which regulate the flow of ingesta into the descending colon (Salamon et al 2007, Cruise and Brewer, 1994). The rectum often contains submucosal lymphocytes rather than areas of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Marked plasma-cell infiltrations into the intestinal tract have been described (Salamon et al 2007). In the small intestine, mucosal erosions, dilatation of lacteals and blunting of overlying villi occur in conjunction with a severe plasma-cell infiltration into the lamina propria (Percy & Barthold 2007).

Rabbits may occasionally be affected by enteric infectious diseases; however, breakdowns in test facility closed systems are rare and usually result in parasitic disease only. Other than coccidiosis, which may cause clinical disease that could compromise a toxicology study, parasitic lesions are generally only incidental interesting background findings. Adult nematodes of Passalurus ambiguus (pinworm) (Fig. 7.6), may occasionally be observed in the cecum and colon. Larval forms may be seen in the mucosa of the small intestine or cecum. Evidence of parasitic transit through the intestine may manifest as mineralized parasitic granulomata. Cysticercus larvae of the tapeworm Taenia pisiformis are occasionally seen hanging from the mesentery or embedded in the liver parenchyma (Soulsby 1986), though this would be a rare finding in purpose-bred laboratory rabbits.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree