Paul P. Calle, Janis Ott Joslin

New World and Old World Monkeys

The primate order may be broadly divided into prosimians, New World (NW) and Old World (OW) monkeys, and great apes.13,15,17,24,47,48 The NW and OW monkeys, which are the subject of this chapter, represent over 270 species, with several new species described in the last decade. NW monkeys are in the Platyrrhini parvorder, which includes the Cebidae, Aotidae, Pitheciidae, and Atelidae families. The Callitrichinae subfamily of the Cebidae family consists of marmosets and tamarins, which are the smallest monkey species. The rest of the NW monkeys are small- to medium-sized monkeys such as squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sp.), capuchin monkeys (Cebus sp.), spider monkeys (Ateles sp.). OW monkeys are all in the Catarrhini parvorder and the Cercopithecidae family. They are medium- to large-sized monkeys such as macaques (Macaca sp.) and baboons (Papio sp.) (Table 37-1).17,24,47,48

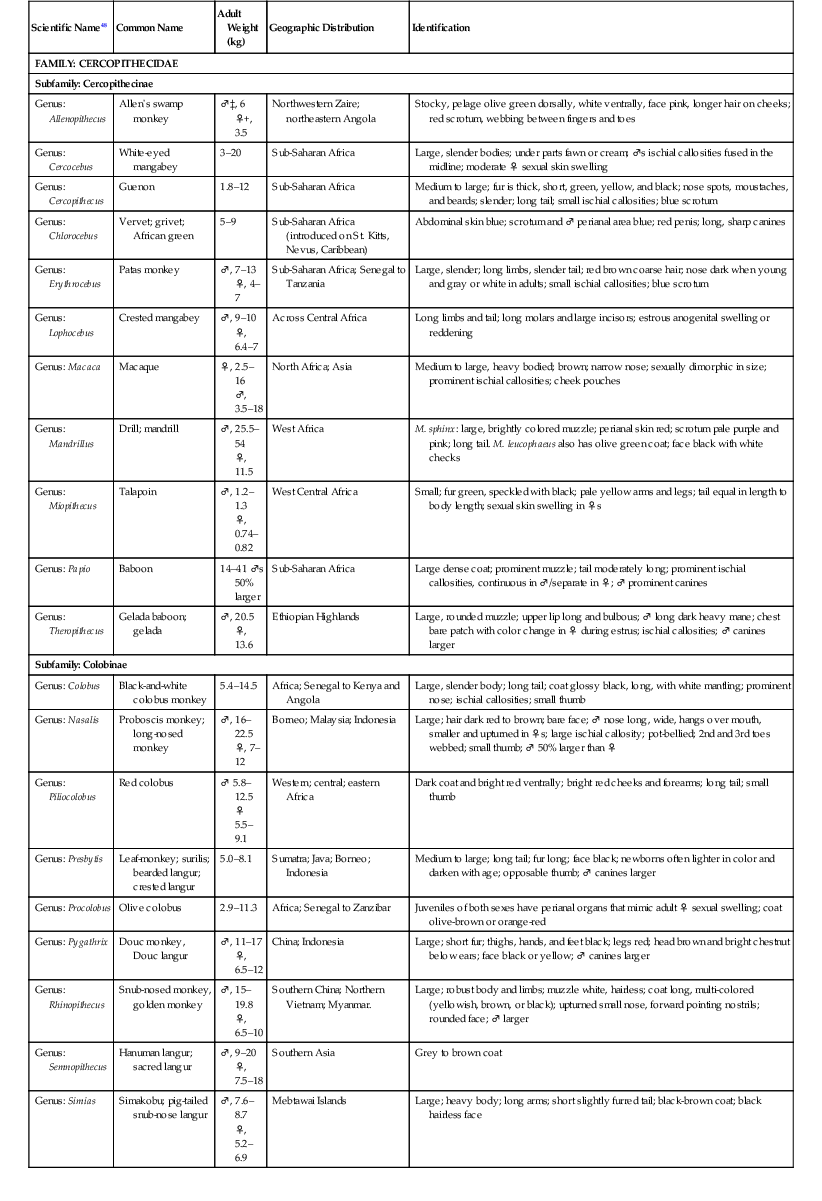

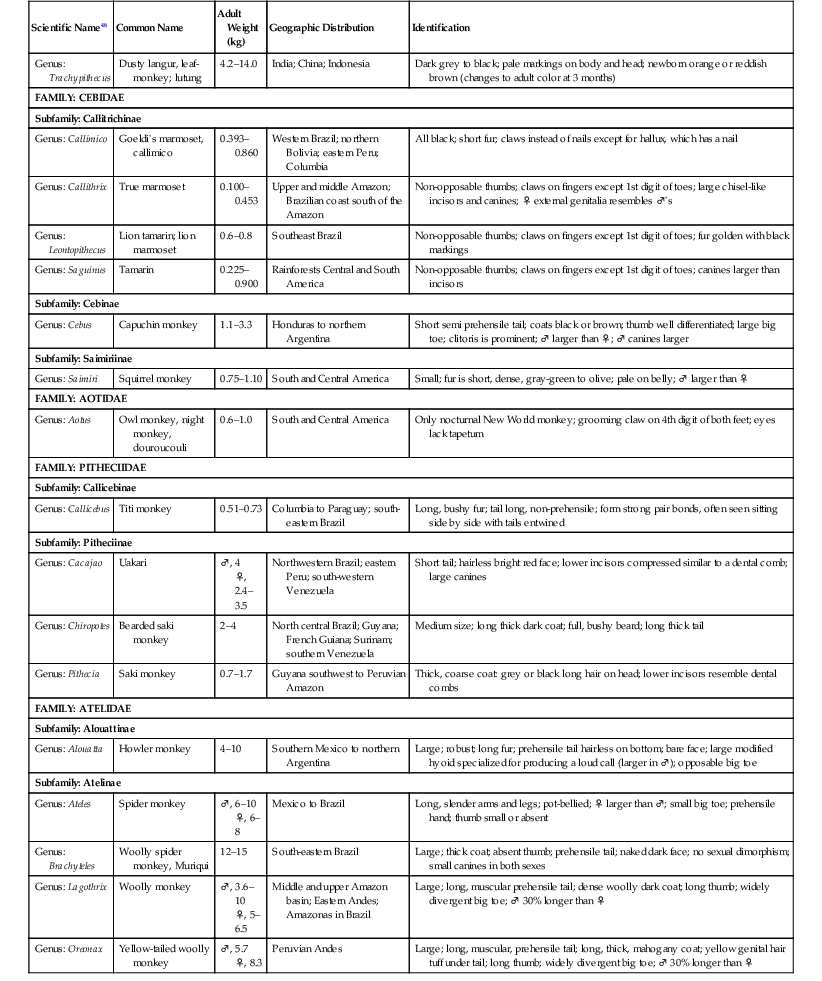

TABLE 37-1

Biologic Information for New World and Old World Monkeys17,47,48

| Scientific Name48 | Common Name | Adult Weight (kg) | Geographic Distribution | Identification |

| FAMILY: CERCOPITHECIDAE | ||||

| Subfamily: Cercopithecinae | ||||

| Genus: Allenopithecus | Allen’s swamp monkey | ♂‡, 6 ♀+, 3.5 | Northwestern Zaire; northeastern Angola | Stocky, pelage olive green dorsally, white ventrally, face pink, longer hair on cheeks; red scrotum, webbing between fingers and toes |

| Genus: Cercocebus | White-eyed mangabey | 3–20 | Sub-Saharan Africa | Large, slender bodies; under parts fawn or cream; ♂s ischial callosities fused in the midline; moderate ♀ sexual skin swelling |

| Genus: Cercopithecus | Guenon | 1.8–12 | Sub-Saharan Africa | Medium to large; fur is thick, short, green, yellow, and black; nose spots, moustaches, and beards; slender; long tail; small ischial callosities; blue scrotum |

| Genus: Chlorocebus | Vervet; grivet; African green | 5–9 | Sub-Saharan Africa (introduced on St. Kitts, Nevus, Caribbean) | Abdominal skin blue; scrotum and ♂ perianal area blue; red penis; long, sharp canines |

| Genus: Erythrocebus | Patas monkey | ♂, 7–13 ♀, 4–7 | Sub-Saharan Africa; Senegal to Tanzania | Large, slender; long limbs, slender tail; red brown coarse hair; nose dark when young and gray or white in adults; small ischial callosities; blue scrotum |

| Genus: Lophocebus | Crested mangabey | ♂, 9–10 ♀, 6.4–7 | Across Central Africa | Long limbs and tail; long molars and large incisors; estrous anogenital swelling or reddening |

| Genus: Macaca | Macaque | ♀, 2.5–16 ♂, 3.5–18 | North Africa; Asia | Medium to large, heavy bodied; brown; narrow nose; sexually dimorphic in size; prominent ischial callosities; cheek pouches |

| Genus: Mandrillus | Drill; mandrill | ♂, 25.5–54 ♀, 11.5 | West Africa | M. sphinx: large, brightly colored muzzle; perianal skin red; scrotum pale purple and pink; long tail. M. leucophaeus also has olive green coat; face black with white checks |

| Genus: Miopithecus | Talapoin | ♂, 1.2–1.3 ♀, 0.74–0.82 | West Central Africa | Small; fur green, speckled with black; pale yellow arms and legs; tail equal in length to body length; sexual skin swelling in ♀s |

| Genus: Papio | Baboon | 14–41 ♂s 50% larger | Sub-Saharan Africa | Large dense coat; prominent muzzle; tail moderately long; prominent ischial callosities, continuous in ♂/separate in ♀; ♂ prominent canines |

| Genus: Theropithecus | Gelada baboon; gelada | ♂, 20.5 ♀, 13.6 | Ethiopian Highlands | Large, rounded muzzle; upper lip long and bulbous; ♂ long dark heavy mane; chest bare patch with color change in ♀ during estrus; ischial callosities; ♂ canines larger |

| Subfamily: Colobinae | ||||

| Genus: Colobus | Black-and-white colobus monkey | 5.4–14.5 | Africa; Senegal to Kenya and Angola | Large, slender body; long tail; coat glossy black, long, with white mantling; prominent nose; ischial callosities; small thumb |

| Genus: Nasalis | Proboscis monkey; long-nosed monkey | ♂, 16–22.5 ♀, 7–12 | Borneo; Malaysia; Indonesia | Large; hair dark red to brown; bare face; ♂ nose long, wide, hangs over mouth, smaller and upturned in ♀s; large ischial callosity; pot-bellied; 2nd and 3rd toes webbed; small thumb; ♂ 50% larger than ♀ |

| Genus: Piliocolobus | Red colobus | ♂ 5.8–12.5 ♀ 5.5–9.1 | Western; central; eastern Africa | Dark coat and bright red ventrally; bright red cheeks and forearms; long tail; small thumb |

| Genus: Presbytis | Leaf-monkey; surilis; bearded langur; crested langur | 5.0–8.1 | Sumatra; Java; Borneo; Indonesia | Medium to large; long tail; fur long; face black; newborns often lighter in color and darken with age; opposable thumb; ♂ canines larger |

| Genus: Procolobus | Olive colobus | 2.9–11.3 | Africa; Senegal to Zanzibar | Juveniles of both sexes have perianal organs that mimic adult ♀ sexual swelling; coat olive-brown or orange-red |

| Genus: Pygathrix | Douc monkey, Douc langur | ♂, 11–17 ♀, 6.5–12 | China; Indonesia | Large; short fur; thighs, hands, and feet black; legs red; head brown and bright chestnut below ears; face black or yellow; ♂ canines larger |

| Genus: Rhinopithecus | Snub-nosed monkey, golden monkey | ♂, 15–19.8 ♀, 6.5–10 | Southern China; Northern Vietnam; Myanmar. | Large; robust body and limbs; muzzle white, hairless; coat long, multi-colored (yellowish, brown, or black); upturned small nose, forward pointing nostrils; rounded face; ♂ larger |

| Genus: Semnopithecus | Hanuman langur; sacred langur | ♂, 9–20 ♀, 7.5–18 | Southern Asia | Grey to brown coat |

| Genus: Simias | Simakobu; pig-tailed snub-nose langur | ♂, 7.6–8.7 ♀, 5.2–6.9 | Mebtawai Islands | Large; heavy body; long arms; short slightly furred tail; black-brown coat; black hairless face |

| Genus: Trachypithecus | Dusty langur, leaf-monkey; lutung | 4.2–14.0 | India; China; Indonesia | Dark grey to black; pale markings on body and head; newborn orange or reddish brown (changes to adult color at 3 months) |

| FAMILY: CEBIDAE | ||||

| Subfamily: Callitrichinae | ||||

| Genus: Callimico | Goeldi’s marmoset, callimico | 0.393–0.860 | Western Brazil; northern Bolivia; eastern Peru; Columbia | All black; short fur; claws instead of nails except for hallux, which has a nail |

| Genus: Callithrix | True marmoset | 0.100–0.453 | Upper and middle Amazon; Brazilian coast south of the Amazon | Non-opposable thumbs; claws on fingers except 1st digit of toes; large chisel-like incisors and canines; ♀ external genitalia resembles ♂’s |

| Genus: Leontopithecus | Lion tamarin; lion marmoset | 0.6–0.8 | Southeast Brazil | Non-opposable thumbs; claws on fingers except 1st digit of toes; fur golden with black markings |

| Genus: Saguinus | Tamarin | 0.225–0.900 | Rainforests Central and South America | Non-opposable thumbs; claws on fingers except 1st digit of toes; canines larger than incisors |

| Subfamily: Cebinae | ||||

| Genus: Cebus | Capuchin monkey | 1.1–3.3 | Honduras to northern Argentina | Short semi prehensile tail; coats black or brown; thumb well differentiated; large big toe; clitoris is prominent; ♂ larger than ♀; ♂ canines larger |

| Subfamily: Saimiriinae | ||||

| Genus: Saimiri | Squirrel monkey | 0.75–1.10 | South and Central America | Small; fur is short, dense, gray-green to olive; pale on belly; ♂ larger than ♀ |

| FAMILY: AOTIDAE | ||||

| Genus: Aotus | Owl monkey, night monkey, douroucouli | 0.6–1.0 | South and Central America | Only nocturnal New World monkey; grooming claw on 4th digit of both feet; eyes lack tapetum |

| FAMILY: PITHECIIDAE | ||||

| Subfamily: Callicebinae | ||||

| Genus: Callicebus | Titi monkey | 0.51–0.73 | Columbia to Paraguay; south-eastern Brazil | Long, bushy fur; tail long, non-prehensile; form strong pair bonds, often seen sitting side by side with tails entwined |

| Subfamily: Pitheciinae | ||||

| Genus: Cacajao | Uakari | ♂, 4 ♀, 2.4–3.5 | Northwestern Brazil; eastern Peru; south-western Venezuela | Short tail; hairless bright red face; lower incisors compressed similar to a dental comb; large canines |

| Genus: Chiropotes | Bearded saki monkey | 2–4 | North central Brazil; Guyana; French Guiana; Surinam; southern Venezuela | Medium size; long thick dark coat; full, bushy beard; long thick tail |

| Genus: Pithecia | Saki monkey | 0.7–1.7 | Guyana southwest to Peruvian Amazon | Thick, coarse coat: grey or black long hair on head; lower incisors resemble dental combs |

| FAMILY: ATELIDAE | ||||

| Subfamily: Alouattinae | ||||

| Genus: Alouatta | Howler monkey | 4–10 | Southern Mexico to northern Argentina | Large; robust; long fur; prehensile tail hairless on bottom; bare face; large modified hyoid specialized for producing a loud call (larger in ♂); opposable big toe |

| Subfamily: Atelinae | ||||

| Genus: Ateles | Spider monkey | ♂, 6–10 ♀, 6–8 | Mexico to Brazil | Long, slender arms and legs; pot-bellied; ♀ larger than ♂; small big toe; prehensile hand; thumb small or absent |

| Genus: Brachyteles | Woolly spider monkey, Muriqui | 12–15 | South-eastern Brazil | Large; thick coat; absent thumb; prehensile tail; naked dark face; no sexual dimorphism; small canines in both sexes |

| Genus: Lagothrix | Woolly monkey | ♂, 3.6–10 ♀, 5–6.5 | Middle and upper Amazon basin; Eastern Andes; Amazonas in Brazil | Large; long, muscular prehensile tail; dense woolly dark coat; long thumb; widely divergent big toe; ♂ 30% longer than ♀ |

| Genus: Oreonax | Yellow-tailed woolly monkey | ♂, 5.7 ♀, 8.3 | Peruvian Andes | Large; long, muscular, prehensile tail; long, thick, mahogany coat; yellow genital hair tuff under tail; long thumb; widely divergent big toe; ♂ 30% longer than ♀ |

kg, Kilogram; ‡♂, male; + ♀, female.

NW and OW monkeys exhibit a range of biology, behavior, and environmental niches with adaptations for those specializations and range across Asia, Africa, South America, and Central America. NW monkeys are generally arboreal and live in tropical forests. OW monkeys may be arboreal and inhabit forests or largely terrestrial and live in more open grasslands (i.e., baboon species); the range of some macaques extends to high elevations (i.e., Japanese snow monkey M. fuscata). Most are diurnal, but some are largely nocturnal. In general, monkeys live in medium- to large-sized troops, with a structured dominance hierarchy consisting of a dominant male, multiple females of various ages, and young males. However, some species are more solitary and live in smaller family groups, multi-male troops, or groups in which females are less submissive. They are intelligent and exhibit tool use, prolonged maturation periods, long gestations, extended life spans, complex social relationships that include grooming of troop members, formation of alliances, long-term relationships, use of tactical deceptive behaviors, and infanticide following the ascension of a new male to dominance. They have many valuable environmental roles, including a significant role in seed dispersal.13,17,24

Overall, more than half of all nonhuman primate species face the threat of extinction. The greatest threats are posed by habitat destruction, modification, and fragmentation, as well as both the local and the international bushmeat trade.16,24,41 Because of the threatened and endangered status of many nonhuman primates, obtaining and possessing these species are governed by national and international regulations such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), in the United States by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and various state regulations, and similar agencies in other countries.

Monkeys are popular species for exhibition and biomedical research; however, they do not make good pets, and private ownership is illegal in many parts of the world. Because of a shared evolutionary history, human primates are excellent models for nonhuman primate anatomy, biology, physiology, diseases, therapeutics, and pharmacology. Much more is written about human primates in these disciplines, which provides a ready source of comparative medical information that may be applied to the care of nonhuman primates.

Unique Anatomy

Nonhuman primates have anatomic features very similar to those of humans, including raised papillary ridges (fingerprints); ocular adaptations, including convergent eye sockets resulting in binocular vision, an overlap of visual fields which enables stereoscopic vision, rods and cones for color vision, and a retinal fovea centralis for sharp imaging; grasping hands; large brains; clavicles; two pectoral mammae; and heterodont dentition. The dental formula for all OW monkeys is 2 : 1 : 2 : 3 and 2 : 1 : 2 : 3 and for all NW monkeys 2 : 1 : 3 : 3 and 2 : 1 : 3 : 3 except for the Callithrix, Leontopithecus, Saguinus, and Cebus, which have the same dental formula as OW monkeys.

Biologic data for representative species are listed in Table 37-1. Prehensile tails are only found in some NW monkeys such as howler monkeys (Alouatta sp.) and spider monkeys, and ischial callosities occur in OW monkeys.13,17,24 Opposable thumbs are found in most OW monkeys, although some such as colobus monkeys (Colobus sp.) have vestigial thumbs. NW and OW monkeys range in size from the smallest monkey species the approximately 120-gram (g) pygmy marmoset (Callithrix [Cebuella] pygmaea), although some prosimians are smaller, to the largest monkey species the approximately 30-kilogram (kg) mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx), which has colorful facial ridges and a bare face.

In some species such as baboons, a dramatic sexual size dimorphism in size exists, the males being significantly larger than the females and possessing large canine teeth, which may inflict serious wounds. Howler monkeys have elaborately enlarged hyoid bones that help create the unique vocalization for which they are named; male lion-tailed macaques (M. silenus) have a flamboyant gray mane; douc langurs (Pygathrix sp.) are strikingly beautiful; and the male proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus) have a significantly enlarged nose.

Laryngeal diverticula (air sacs) are present in most NW and OW monkeys, and many OW monkey species also have cheek pouches in which food is stored during foraging. The OW Colobinae subfamily (colobus, langurs, proboscis, etc.) are folivorous, with diets consisting largely of leaves and other vegetation. They possess complex sacculated stomachs in which foregut microbial fermentation takes place, and this deactivates some plant toxins and generates volatile fatty acids that are absorbed as an energy source. Similarly, NW howler monkeys have hindgut fermentation in the cecum and colon.13,17,24 The complex foreguts of the OW Colobinae and the hindgut of NW howler monkeys are susceptible to protozoal (Amoeba sp.) infection. Antibiotic treatment in these species may disrupt normal microbial digestion, resulting in dysbiosis and diarrhea. If this does not resolve with discontinuation of antibiotic treatment, transfaunation of stomach contents from a healthy OW monkey from the same or a closely related species or, in the case of the NW howler monkeys, feces from another howler, may be performed.

Special Housing Requirements

Housing for NW and OW monkeys must meet their social, environmental, physical, and behavioral needs, in addition to addressing disease transmission concerns. Because of advances in exhibit design and construction, in medical treatments, and in the art and science of captive care, naturalistic exhibits are much more common than was previously possible.

Effective parasite treatment regimens, in particular, have enhanced the ability to maintain nonhuman primates in naturalistic exhibits. Design of exhibit and off-exhibit holding areas should prevent disease transmission between human and nonhuman primates through the use of glass or physical separation that is adequate to prevent airborne disease transmission between the public or workers and the nonhuman primates. This should be enhanced through management and husbandry protocols to ensure the health and safety of both human and nonhuman primates.

With medium- and large-sized nonhuman primates, it is recommended that the animals be shifted out of the exhibit for servicing. In the United States, nonhuman primate behavioral enrichment is mandated by the United States Department of Agriculture Animal Welfare Act, and all licensed holders are required to have an active behavioral enrichment program. A complex physical environment that usually incorporates arboreal elements, distribution of food and non-food enrichment items throughout the substrate and exhibit, and housing animals in species-specific normal social groups are all critical components in the maintenance of healthy nonhuman primates.34

Nutrition and Diet

NW and OW monkeys may be either generalized or specialized feeders, with the majority consuming plants, fruits, nuts, insects, and other foods such as small invertebrates.13,17 Some dietary specializations are a gummivorous diet or a largely frugivorous, herbivorous, omnivorous, faunivorous, or folivorous diet, with the digestive tract adaptations reflecting the species diet. In all cases, replication of the natural diet is recommended. Because the wild diet is varied, the common practice is to offer a variety of food items, in the belief that nonhuman primates will self-select proper food items for a balanced diet. Unfortunately, this is often not the case, and nutritional problems such as obesity, nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, gastrointestinal (GI) problems, and hypoproteinemia may result from this feeding strategy. Nonhuman primates will ingest 2% to 4% of their body weight daily. In contrast to wild fruits and vegetables, many commercially available varieties cultivated for human consumption are lower in protein (2% to 6% of dry matter [DM]), calcium (0.03% to 0.3% of DM), and fiber, and higher in sugar, than their wild counterparts. To prevent overconsumption, nonhuman primates should generally be fed no more than 30% of DM as produce. Because produce contains 10% to 20% of DM, canned foods are 40% DM, and biscuits are 90% DM, the diet fed may be 70% produce and 30% biscuits by weight. If a canned diet is fed, 50% produce and 50% canned diet should be fed by weight, which will equal 30% of the DM in produce.17

In general, nonhuman primates have a minimal 7% to 10% protein requirement (DM basis), and pregnant or lactating animals require 12.5% protein. The National Research Council (NRC) recommends 16% protein on a DM basis for most nonhuman primates and 25% for New World monkeys.17 Commercially prepared diets vary from 16% to 26.1% protein (lower protein diets are used for most nonhuman primates and higher protein ones for New World monkeys). Because most nonhuman primates are fed commercial diets along with low-protein items such as fruit, the total diet offered more closely approximates the requirements.

All nonhuman primates require appropriate ratios and amounts of dietary calcium and phosphorus. Calcium deficiency, or imbalance in calcium and phosphorus ratios, will result in metabolic bone disease (“simian bone disease” or rickets). NW monkeys require preformed dietary vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Sunlight or appropriate ultraviolet (UV) wavelength exposure is also important for calcium metabolism. Marmosets have a vitamin D3 requirement higher than that for other NW monkeys. Additionally, most marmosets and tamarins are fed insects, which are low in calcium. To balance the calcium and phosphorus levels, the insects must be fed a calcium-rich diet (8%) for at least 48 hours before being consumed. Nursing infants also have higher vitamin D requirements for normal skeletal growth, and if this is not met, the infant may develop nutritional deficiency. Both NW and OW monkeys require a dietary source of vitamin C. Signs of deficiency may include gingival hemorrhage, loose teeth, epiphyseal fractures, subperiosteal hemorrhage, decreased polymorphonuclear leukocyte activity, normocytic normochromic anemia, and exophthalmos. In young squirrel monkeys, cephalhematoma is the most common sign of vitamin C deficiency. The requirements for primates have been estimated to be 1 to 25 milligrams per kilogram per day (mg/kg/day), and stress effects on required vitamin C may account for the wide range in the daily requirements.17

Folivorous species (Colobinae subfamily) present special feeding challenges and require diets high in fiber. These species typically have either a large complex stomach or enlarged ceca and colon. Trachypithecus, Semnopithecus, Presbytis, and Colobus species have sacculated stomachs with two bands of longitudinal teniae. Presbytis species have a well-developed intestinal tract.17 Commercially available diets high in fiber, with a 25% neutral detergent fiber and 12% to 16% acid detergent fiber, may be supplemented with leafy vegetables and browse, more closely approximating natural diets. Feeding frequently (three or more times daily) is important to promote continuous fermentation. Some Colobus species develop gluten sensitivity enteropathy when fed diets containing wheat, barley, rye, or oats. Gluten-free high-fiber monkey biscuits (25% neutral detergent fiber) are available and should be fed to Colobus species or any monkey with gluten intolerance. Commercial biscuits are formulated to comprise no less than 50% of the diet on an as-fed basis. Any diet changes for folivorous species should be done gradually to allow time for adjustment of gastric microflora. Diets should be supplemented with browse; however, both exhibit plants and browse that are high in lignin or indigestible fibers (e.g., acacia or browse with fibrous bark or foliage) cannot be digested by gastric microflora and may therefore result in phytobezoar obstruction.5,17 Cebidae species are mostly omnivores and many feed on fruit and leaves. Aotus species mainly consume insects and bats, and both have simple stomachs with a variable length small intestine. The faunivores have a simple stomach and hindgut and a long small intestine. Gummivorous species (i.e., pygmy marmosets) have longer retention times for fermentation.17

A range of nutritionally complete canned or biscuit primate diets are commercially available, and the NW monkey diets include vitamin D3. A combination of these commercially prepared diets and a mix of fresh fruits, vegetables, produce, and browse, as indicated by the dietary specialization, are most commonly fed. In addition, a variety of enrichment items should be planned as components of the calculated daily dietary requirements. A good general guide is that enrichment “treats” should constitute less than 10% of the daily dietary requirements to avoid dilution of the nutritional quality of the diet by overconsumption of enrichment “treats.” Often these supplemental environmental or behavioral enrichment items are not nutritionally significant but are very important for the psychological and social stimulation they provide.17,21,22,32 Dietary indiscretion from inappropriate diets, feeding by visitors, or gorging, may lead to GI upset; good exhibit design along with management and husbandry protocols minimize this risk.

Restraint and Handling

Physical restraint is only recommended for smaller nonhuman primate species and should only be performed by experienced handlers. Improperly performed physical restraint may be dangerous and stressful for the nonhuman primate and dangerous for the handler. Nonhuman primates weighing less than about 10 kg (depending on the level of the handler’s experience, type of housing, and the monkey’s disposition) may be manually restrained using appropriate gloves and nets; however, this is not recommended for macaque species because of the risk of herpes B virus exposure. However, larger or more aggressive monkeys should not be restrained in this way; instead, specialized restraint devices (“squeeze cages”) or chemical immobilization should be employed. In addition, behavioral training may be used to enlist the voluntary participation of nonhuman primates in medical and management procedures.

Anesthesia and Surgery

A number of anesthetic protocols may be used for immobilization and anesthesia of monkeys (http://www.primatevets.org/education).17,18,29,43 The most commonly employed for medium- to large-sized species are either ketamine alone (6–10 mg/kg, intramuscularly [IM]), or ketamine (2–4 mg/kg, IM) in combination with either medetomidine (0.04–0.06 mg/kg, IM) or dexmedetomidine (0.02–0.03 mg/kg, IM), typically combined in one syringe. When used in combination, the effects of the medetomidine or dexmedetomidine may be antagonized by the administration of atipamezole (IM at 5× the dose of medetomidine or 10× the dose of dexmedetomidine) to significantly shorten recovery time.

Reversal is best accomplished by administering the antagonist about 20 minutes or longer after initial dosing to allow for ketamine metabolism and therefore avoid residual ketamine sedation, which could result in ataxia or disorientation during recovery. If ketamine is not available, a combination of tiletamine and zolazepam may be used 2–5 mg/kg, IM); however, this drug combination results in considerably longer recovery times, which should be considered while planning how and where the monkey will recover from anesthesia. Atropine is not generally administered unless a specific reason for its use exists. All of these protocols are effective in inducing excellent muscle relaxation. Other injectable anesthetic protocols may be used in particular circumstances, to achieve specific purposes, or based on drug availability.

Doses are typically delivered by hand injection to monkeys that are conditioned to voluntarily receive injections or are manually restrained by hand, in a net, or in a restraint device; or the injection is delivered by pole syringe or by dart for other situations. Smaller species such as callitrichids may be anesthetized with an inhalant anesthetic such as isoflurane, administered either via a face mask to a monkey that may be safely manually restrained or by placing the monkey into an induction chamber. Once anesthetized by any method, anesthesia may be prolonged or the anesthetic plane deepened through the administration of inhalant anesthesia via a face mask.

Comfortable positioning, maintaining appropriate body temperature (i.e., provision of a recirculating hot water pad, heating pads, hot water bottles, heat lamps, etc.), and lubrication of the eyes with ophthalmic ointment are all important considerations, especially for prolonged anesthesia. For longer or more complicated procedures, or when a monkey has significant illness, endotracheal intubation is recommended because it allows for better respiratory support, greater control of the anesthetic plane, and a more effective emergency response, as needed. Similarly, in those situations, placement of an indwelling venous catheter is recommended for administration of fluids and immediate access for administration of emergency drugs.

Anesthesia is typically monitored by thoracic auscultation of heart and respiratory rates, observation of mucous membrane color, assessment of peripheral pulse (typically the femoral artery), electrocardiography (ECG) recording, and pulse oximetry. End tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) measurement, direct and indirect blood pressure monitoring, and assessment of venous or arterial blood gases may also be performed as would be done in humans or domestic animals, as indicated by the animal’s condition or duration of anesthesia. Documentation of the anesthetic drugs, doses, intervals, and physiologic parameters in an anesthesia report is valuable for reference during the anesthesia event and for future consultation.

Common surgical procedures of monkeys include repair of lacerations resulting from conspecific aggression; abscess debridement and treatment; dental extractions (especially carnasial tooth root infections resulting in facial abscesses); root canal procedures; and fracture fixation. All are performed by standard veterinary or human pediatric techniques. GI linear foreign bodies from consumption of inappropriate plant material,5 and similar complications resulting from consumption of other foreign bodies have been observed. Lion-tailed macaques have a predisposition to develop inguinal hernias, and golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) more often have congenital diaphragmatic hernias compared with other species; these problems may be surgically corrected.4,23,28

Elective surgeries include vasectomy, castration, tubal ligation, and ovariohysterectomy for contraception. Emergency and therapeutic reproductive procedures include cesarean section, treatment of placental abruption or placenta previa, and treatment of endometriosis.17,26 A postoperative concern is that the monkey with its nimble fingers, may remove the sutures, so suture lines should be buried by using subcuticular patterns, whenever possible. However, in the majority of cases, the monkeys leave the sutures alone.

Diagnostics

Most diagnostic techniques and options employed for small animals or in human pediatrics are applicable to NW and OW monkeys. Radiography, with routine lateral and ventrodorsal positioning, is standard; for larger species, obese individuals, or folivorous primates that have a large fluid-filled complex stomach, an upright sitting position and horizontal beam radiography will enhance thoracic detail.17 Mammography machines provide exquisitely detailed radiographic visualization and may be used for whole body radiography in smaller species or to image the extremities of larger species. Ultrasonography is routinely employed using standard techniques and ultrasound probes. For ultrasonographic visualization of the female reproductive tract, if animal and probe sizes permit, intrarectal ultrasonography will provide the best visualization of the ovaries and the uterus. Flexible and rigid endoscopy allow minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures to be performed.

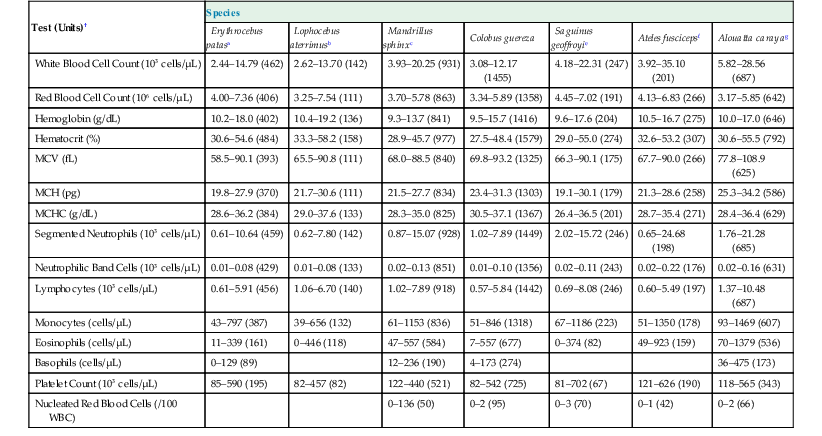

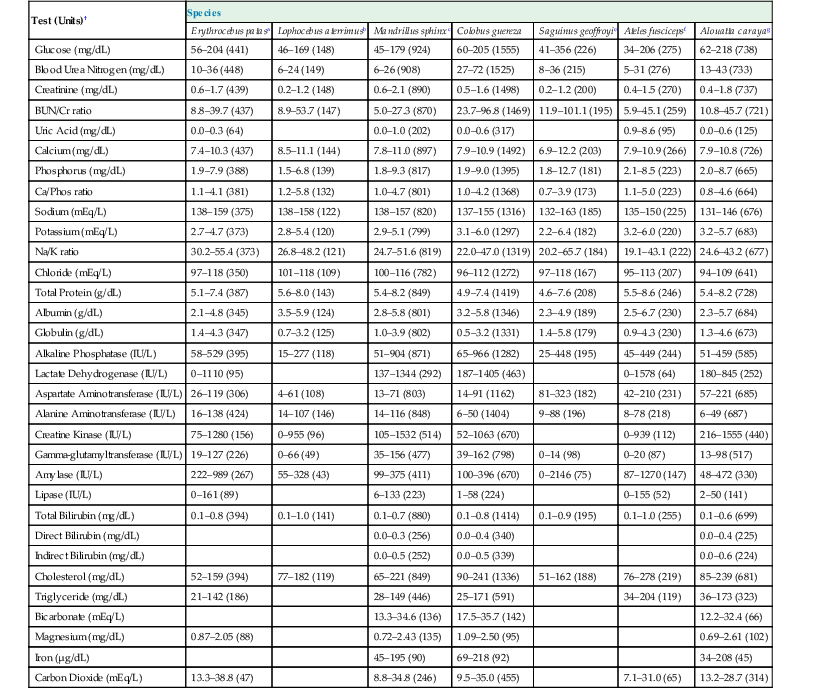

The femoral, cephalic, or saphenous veins are usually used for venipuncture, and the femoral artery is readily accessed for arterial sampling.17 Routine hematologic and biochemical screening and species-specific viral serology are commonly performed. Normal physiologic ranges for representative species are provided in Tables 37-2 and 37-3 (see http://www.primatevets.org/education).26,35,37,42

Table 37-2

Hematological Reference Intervals from Captive Representative Species of New World and Old World Monkeys from Composite MedARKS Records*

| Test (Units)† | Species | ||||||

| Erythrocebus patasa | Lophocebus aterrimusb | Mandrillus sphinxc | Colobus guereza | Saguinus geoffroyie | Ateles fuscicepsf | Alouatta carayag | |

| White Blood Cell Count (103 cells/µL) | 2.44–14.79 (462) | 2.62–13.70 (142) | 3.93–20.25 (931) | 3.08–12.17 (1455) | 4.18–22.31 (247) | 3.92–35.10 (201) | 5.82–28.56 (687) |

| Red Blood Cell Count (106 cells/µL) | 4.00–7.36 (406) | 3.25–7.54 (111) | 3.70–5.78 (863) | 3.34–5.89 (1358) | 4.45–7.02 (191) | 4.13–6.83 (266) | 3.17–5.85 (642) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.2–18.0 (402) | 10.4–19.2 (136) | 9.3–13.7 (841) | 9.5–15.7 (1416) | 9.6–17.6 (204) | 10.5–16.7 (275) | 10.0–17.0 (646) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 30.6–54.6 (484) | 33.3–58.2 (158) | 28.9–45.7 (977) | 27.5–48.4 (1579) | 29.0–55.0 (274) | 32.6–53.2 (307) | 30.6–55.5 (792) |

| MCV (fL) | 58.5–90.1 (393) | 65.5–90.8 (111) | 68.0–88.5 (840) | 69.8–93.2 (1325) | 66.3–90.1 (175) | 67.7–90.0 (266) | 77.8–108.9 (625) |

| MCH (pg) | 19.8–27.9 (370) | 21.7–30.6 (111) | 21.5–27.7 (834) | 23.4–31.3 (1303) | 19.1–30.1 (179) | 21.3–28.6 (258) | 25.3–34.2 (586) |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 28.6–36.2 (384) | 29.0–37.6 (133) | 28.3–35.0 (825) | 30.5–37.1 (1367) | 26.4–36.5 (201) | 28.7–35.4 (271) | 28.4–36.4 (629) |

| Segmented Neutrophils (103 cells/µL) | 0.61–10.64 (459) | 0.62–7.80 (142) | 0.87–15.07 (928) | 1.02–7.89 (1449) | 2.02–15.72 (246) | 0.65–24.68 (198) | 1.76–21.28 (685) |

| Neutrophilic Band Cells (103 cells/µL) | 0.01–0.08 (429) | 0.01–0.08 (133) | 0.02–0.13 (851) | 0.01–0.10 (1356) | 0.02–0.11 (243) | 0.02–0.22 (176) | 0.02–0.16 (631) |

| Lymphocytes (103 cells/µL) | 0.61–5.91 (456) | 1.06–6.70 (140) | 1.02–7.89 (918) | 0.57–5.84 (1442) | 0.69–8.08 (246) | 0.60–5.49 (197) | 1.37–10.48 (687) |

| Monocytes (cells/µL) | 43–797 (387) | 39–656 (132) | 61–1153 (836) | 51–846 (1318) | 67–1186 (223) | 51–1350 (178) | 93–1469 (607) |

| Eosinophils (cells/µL) | 11–339 (161) | 0–446 (118) | 47–557 (584) | 7–557 (677) | 0–374 (82) | 49–923 (159) | 70–1379 (536) |

| Basophils (cells/µL) | 0–129 (89) | 12–236 (190) | 4–173 (274) | 36–475 (173) | |||

| Platelet Count (103 cells/µL) | 85–590 (195) | 82–457 (82) | 122–440 (521) | 82–542 (725) | 81–702 (67) | 121–626 (190) | 118–565 (343) |

| Nucleated Red Blood Cells (/100 WBC) | 0–136 (50) | 0–2 (95) | 0–3 (70) | 0–1 (42) | 0–2 (66) | ||

* Sample Selection Criteria: No selection by gender, all ages combined, animal was classified as healthy at the time of sample collection, sample was not deteriorated.

† Values are given as a reference interval (number of samples used to calculate reference interval).

a Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Erythrocebus_patas_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

b Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Lophocebus_aterrimus_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

c Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Mandrillus_sphinx_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

e Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Saguinus_geoffroyi_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

f Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Ateles_fusciceps_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

g Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Alouatta_caraya_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

dTeare JA, ed: 2013, “Colobus_guereza_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

MCV, Mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

Table 37-3

Serum Biochemical Reference Intervals from Captive Representative Species of New World and Old World Monkeys from Composite MedARKS Records*

| Test (Units)† | Species | ||||||

| Erythrocebus patasa | Lophocebus aterrimusb | Mandrillus sphinxc | Colobus guereza | Saguinus geoffroyie | Ateles fuscicepsf | Alouatta carayag | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 56–204 (441) | 46–169 (148) | 45–179 (924) | 60–205 (1555) | 41–356 (226) | 34–206 (275) | 62–218 (738) |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | 10–36 (448) | 6–24 (149) | 6–26 (908) | 27–72 (1525) | 8–36 (215) | 5–31 (276) | 13–43 (733) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6–1.7 (439) | 0.2–1.2 (148) | 0.6–2.1 (890) | 0.5–1.6 (1498) | 0.2–1.2 (200) | 0.4–1.5 (270) | 0.4–1.8 (737) |

| BUN/Cr ratio | 8.8–39.7 (437) | 8.9–53.7 (147) | 5.0–27.3 (870) | 23.7–96.8 (1469) | 11.9–101.1 (195) | 5.9–45.1 (259) | 10.8–45.7 (721) |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 0.0–0.3 (64) | 0.0–1.0 (202) | 0.0–0.6 (317) | 0.9–8.6 (95) | 0.0–0.6 (125) | ||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 7.4–10.3 (437) | 8.5–11.1 (144) | 7.8–11.0 (897) | 7.9–10.9 (1492) | 6.9–12.2 (203) | 7.9–10.9 (266) | 7.9–10.8 (726) |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 1.9–7.9 (388) | 1.5–6.8 (139) | 1.8–9.3 (817) | 1.9–9.0 (1395) | 1.8–12.7 (181) | 2.1–8.5 (223) | 2.0–8.7 (665) |

| Ca/Phos ratio | 1.1–4.1 (381) | 1.2–5.8 (132) | 1.0–4.7 (801) | 1.0–4.2 (1368) | 0.7–3.9 (173) | 1.1–5.0 (223) | 0.8–4.6 (664) |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138–159 (375) | 138–158 (122) | 138–157 (820) | 137–155 (1316) | 132–163 (185) | 135–150 (225) | 131–146 (676) |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 2.7–4.7 (373) | 2.8–5.4 (120) | 2.9–5.1 (799) | 3.1–6.0 (1297) | 2.2–6.4 (182) | 3.2–6.0 (220) | 3.2–5.7 (683) |

| Na/K ratio | 30.2–55.4 (373) | 26.8–48.2 (121) | 24.7–51.6 (819) | 22.0–47.0 (1319) | 20.2–65.7 (184) | 19.1–43.1 (222) | 24.6–43.2 (677) |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 97–118 (350) | 101–118 (109) | 100–116 (782) | 96–112 (1272) | 97–118 (167) | 95–113 (207) | 94–109 (641) |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 5.1–7.4 (387) | 5.6–8.0 (143) | 5.4–8.2 (849) | 4.9–7.4 (1419) | 4.6–7.6 (208) | 5.5–8.6 (246) | 5.4–8.2 (728) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.1–4.8 (345) | 3.5–5.9 (124) | 2.8–5.8 (801) | 3.2–5.8 (1346) | 2.3–4.9 (189) | 2.5–6.7 (230) | 2.3–5.7 (684) |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 1.4–4.3 (347) | 0.7–3.2 (125) | 1.0–3.9 (802) | 0.5–3.2 (1331) | 1.4–5.8 (179) | 0.9–4.3 (230) | 1.3–4.6 (673) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (IU/L) | 58–529 (395) | 15–277 (118) | 51–904 (871) | 65–966 (1282) | 25–448 (195) | 45–449 (244) | 51–459 (585) |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 0–1110 (95) | 137–1344 (292) | 187–1405 (463) | 0–1578 (64) | 180–845 (252) | ||

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (IU/L) | 26–119 (306) | 4–61 (108) | 13–71 (803) | 14–91 (1162) | 81–323 (182) | 42–210 (231) | 57–221 (685) |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (IU/L) | 16–138 (424) | 14–107 (146) | 14–116 (848) | 6–50 (1404) | 9–88 (196) | 8–78 (218) | 6–49 (687) |

| Creatine Kinase (IU/L) | 75–1280 (156) | 0–955 (96) | 105–1532 (514) | 52–1063 (670) | 0–939 (112) | 216–1555 (440) | |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (IU/L) | 19–127 (226) | 0–66 (49) | 35–156 (477) | 39–162 (798) | 0–14 (98) | 0–20 (87) | 13–98 (517) |

| Amylase (IU/L) | 222–989 (267) | 55–328 (43) | 99–375 (411) | 100–396 (670) | 0–2146 (75) | 87–1270 (147) | 48–472 (330) |

| Lipase (IU/L) | 0–161 (89) | 6–133 (223) | 1–58 (224) | 0–155 (52) | 2–50 (141) | ||

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1–0.8 (394) | 0.1–1.0 (141) | 0.1–0.7 (880) | 0.1–0.8 (1414) | 0.1–0.9 (195) | 0.1–1.0 (255) | 0.1–0.6 (699) |

| Direct Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.0–0.3 (256) | 0.0–0.4 (340) | 0.0–0.4 (225) | ||||

| Indirect Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.0–0.5 (252) | 0.0–0.5 (339) | 0.0–0.6 (224) | ||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 52–159 (394) | 77–182 (119) | 65–221 (849) | 90–241 (1336) | 51–162 (188) | 76–278 (219) | 85–239 (681) |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 21–142 (186) | 28–149 (446) | 25–171 (591) | 34–204 (119) | 36–173 (323) | ||

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 13.3–34.6 (136) | 17.5–35.7 (142) | 12.2–32.4 (66) | ||||

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 0.87–2.05 (88) | 0.72–2.43 (135) | 1.09–2.50 (95) | 0.69–2.61 (102) | |||

| Iron (µg/dL) | 45–195 (90) | 69–218 (92) | 34–208 (45) | ||||

| Carbon Dioxide (mEq/L) | 13.3–38.8 (47) | 8.8–34.8 (246) | 9.5–35.0 (455) | 7.1–31.0 (65) | 13.2–28.7 (314) | ||

* Sample Selection Criteria: No selection by gender, all ages combined, animal was classified as healthy at the time of sample collection, sample was not deteriorated.

† Values are given as a reference interval (number of samples used to calculate the reference interval).

a Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Erythrocebus_patas_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

b Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Lophocebus_aterrimus_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

c Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Mandrillus_sphinx_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

e Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Saguinus_geoffroyi_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

f Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Ateles_fusciceps_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

g Teare JA, ed: 2013, “Alouatta_caraya_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

dTeare JA, ed: 2013, “Colobus_guereza_No_selection_by_gender__All_ages_combined_Conventional_American_units__2013_CD.html” in ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: A CD-ROM., International Species Information System, Bloomington, MN.

Because of the frequency of enteric and diarrheal diseases in monkeys, fecal examination is one of the most commonly employed diagnostic tests. This should include direct examination of fresh thin fecal smears, as this is especially useful for the detection of protozoa such as ameba; a routine flotation examination for helminth larvae or ova; and a fecal sedimentation examination, which will detect the heavy ova of parasites such as Prosthenorchis sp. that are not detected by routine fecal floatation.26 Flagellates are frequently observed on direct fecal smear examinations of diarrheic feces. Although they rarely may be the cause of enteric disease, in most cases, they are nonpathogenic and are secondary to the change in composition of the feces. They proliferate in the liquid composition of diarrheic feces and are shed because of the increase in fecal frequency. NW monkeys frequently have Gongylonema sp. infection of the oral mucous membranes. In addition to fecal screening, a cotton-tipped applicator or similar material may be used to swab along the oral gingival membranes to manually remove the parasites for diagnosis.

Microbial cultures are frequently conducted, and when fecal aerobic culture is performed on feces, a microbiologic enrichment media should be used. This will aid in the culture of enteropathogens such as Salmonella sp., Shigella sp., and Campylobacter sp., all of which are common causes of diarrheal disease in monkeys. Feces may also be submitted for viral screening with electron microscopy (EM) or viral cultures performed. Urine can be collected by urinary catheterization in both male and female NW and OW monkeys if an appropriately sized catheter is available, or by ultrasound guided cystocentesis, manual expression of the urinary bladder, or collected from the substrate for analysis. Other diagnostic tests (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] collection, thoracocentesis, abdominocentesis, etc.) may also be performed using the same principles and procedures as in other species.

Therapeutics

For most therapeutic agents, dosages for NW and OW monkeys are based on guidelines for human pediatric or domestic small animal patients, although some specific recommendations for nonhuman primates are also available (http://www.primatevets.org/education).30,35,40,43 Frequently used antibiotics for enteric, respiratory, or systemic bacterial infections are trimethoprim-sulfa combinations; quinolones; and combinations of aminoglycosides and penicillin and its derivatives. Metronidazole, especially benzoyl metronidazole, which improves palatability, is commonly used for enteric protozoal infections. Various anthelmintics are used for helminth infections. Motility modifiers (e.g., loperamide) and symptomatic treatments (e.g., bismuth subsalicylate) may also be used for treatment of diarrheal diseases.

Enteroparasites may be significant causes of morbidity and mortality, especially in newly imported monkeys. A range of parasiticides are recommended (Table 37-4; http://www.primatevets.org/education) for the treatment of commonly encountered parasites (Table 37-5).

TABLE 37-4

Parasiticides Recommended for New World and Old World Monkeys2,9, 17,19, 33, 40,43

| Generic Name (Trade Name) | Species | Dosage | Route | Comments |

| Albendazole (VALBAZEN) | NW and OW | 25 mg/kg | PO | For Filaroides and Giardia: BID for 5 days |

| Amitraz (Mitaban) | Tamarins | 250 ppm solution | TP | For demodectic mange: place in solution for 2–5 minutes Repeat q14d† for 4 treatments or until lesions resolve |

| Azithromycin (Zithromax) | Macaques | 25–50 mg/kg | SQ | For malaria: SID for 3–10 days In humans, combined with chloroquine |

| NW and OW | 40 mg/kg | IM | Give SID for one day, then 20 mg/kg SID for 2–5 days | |

| Bunamidine (Scolaban) | NW and OW | 25–100 mg/kg | PO | For cestodes: give once |

| Chloroquine phosphate (Arelan) | NW and OW | 2.5–5 mg/kg | IM | For Plasmodium sp.: SID for 4–7 days, then 0.75 mg/kg primaquine PO SID for 14 days Give chloroquine and primaquine separately to prevent toxicity |

| NW and OW | 5 mg/kg | PO; IM | For Entamoeba histolytica: SID for 14 days | |

| NW and OW | 10 mg/kg | PO; IM | For Plasmodium: give once; 6 hours later give 5 mg/kg, and 24 hours later give 5 mg/kg SID for 2 days and then start primaquine PO 0.3 mg/kg SID for 14 days | |

| Clindamycin (Antirobe) | NW and OW | 12.5 mg/kg | PO; IM | For toxoplasmosis: BID for 28 days |

| Dichlorvos (Atgard-V) | NW and OW | 10 mg/kg | PO | For Trichuris sp.: SID for 1–2 days |

| NW and OW | 10–15 mg/kg | PO | For gastrointestinal nematodes: SID for 2–3 days | |

| Diethylcarbamazine Citrate (Filaribits) | Owl Monkey | 6–20 mg/kg | PO | For Filariasis (dipetalonema): SID for 6–15 days |

| 20–40 mg.kg | PO | For Filariasis (dipetalonema): SID for 7–21 days | ||

| Squirrel Monkey | 50 mg/kg | PO | For Filariasis (adults and microfilaria): SID for 10 days | |

| Diiodohydroxyquin [iodoquinol] (Yodoxin) | NW and OW | 10–13.3 mg/kg | PO | For Entamoeba histolytica: TID for 10–20 days Use with metronidazole in severe cases |

| NW and OW | 13.3 mg/kg | PO | For Balantidium coli: TID for 14–21 days | |

| NW and OW | 20 mg/kg | PO | BID for 21 days | |

| NW and OW | 30 mg/kg | PO | SID for 10 days | |

| Dithiazanine sodium (Dizan) | NW and OW | 10–20 mg/kg | PO | For Strongyloides: SID for 3–10 days |

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin) | NW and OW | 2.5 mg/kg | PO | For Balantidium: BID for 1 day, then SID for 10 days |

| Fenbendazole (Panacur) | NW and OW | 10–25 mg/kg | PO | For Anatrichosoma cynomolgi: SID for 3–10 days May result in remission |

| NW and OW | 20 mg/kg | PO | For Strongyloides sp. and Filaroides: SID for 14 days | |

| Marmosets | 20 mg/kg | PO | For Prosthenorchis sp.: SID for 7 days | |

| NW and OW | 25 mg/kg | PO | For Ancylostoma: q7d for 2 times | |

| NW and OW | 50 mg/kg | PO | SID for 3–14 days | |

| For Filaroides: SID for 14 days | ||||

| Flubendazole 5% (Flubenol) | Baboons | 27–50 mg/kg | PO | For Trichuris sp.: BID for 5 days |

| Ivermectin (Ivomec) | NW and OW | 0.2 mg/kg | PO; IM; SQ | For Strongyloides sp., Gongylonema sp., Pneumonyssus sp., Anoplura: give once and repeat in 10–14 days |

| IM | For Ancyclostoma duodenale: give once and repeat in 21 days if needed | |||

| 0.4 µg/kg | IM | For: Strongyloides sp. in macaques: Dilute with propylene glycol | ||

| 0.5 µg/kg | SQ | For Pterygodermatites sp.: SID for 3 days. Dilute in sterile water for smaller species (marmosets) | ||

| Levamisole (Levasole) | Saki Monkeys | 4–5 mg/kg | PO | For oral Spiruridiasis: SID for 6 days |

| NW and OW | 5 mg/kg | PO | Give once and repeat in 3 weeks | |

| NW and OW | 7.5 mg/kg | SQ | For Trichuris sp. and Ancyclostoma sp.: give once; repeat in 2 weeks | |

| NW and OW | 10 mg/kg | PO | For Strongyloides sp., Filaroides, Oesophagostormum sp. and Trichuris | |

| PO or SQ | For Strongyloides sp.: give 2–3 days | |||

| Spider monkeys | 10 mg/kg | — | For Physaloptera sp.: give for 3 days. | |

| Tamarins | 11 mg/kg | — | For Filariasis: give for 10 days along with thiacetarsamide sodium at 0.22 mL/kg BID for 2 days | |

| Mebendazole (Telminic) | NW and OW | 3 mg/kg | PO | For Ancyclostoma sp.: SID for 10 days |

| NW and OW | 15 mg/kg | PO | For Strongyloides sp., Necator, Pterygodermatitis, and Trichuris: SID for 3 days | |

| For Ancyclostoma sp.: SID for 2 days | ||||

| NW and OW | 22 mg/kg | PO | SID for 3 days and then repeat in 2 weeks | |

| NW and OW | 40 mg/kg | PO | For Pterygodermatites sp.: SID for 3 days repeated 3 to 4 times yearly as prevention | |

| NW | 70 mg/kg | PO | For oral spiruridiasis: SID for 3 days Repeat treatment periodically | |

| Callitrichids | 100 mg/kg | PO | For acanthocephalans: treat once every 2 weeks Use as a preventive along with surgical removal of parasite | |

| Mefloquine (Lariam) | NW and OW | 25 mg/kg | PO | For malarial: give one dose |

| Metronidazole (Flagyl) [Metronidazole benzoate (Flagyl-S) may be compounded with flavored syrup, improving palatability] | NW and OW | 10–16.7 mg/kg | PO | For Giardia intestinalis: TID for 5–10 days |

| NW and OW | 11.7–16.7 mg/kg | PO | For Balantidium coli: TID for 10 days | |

| NW and OW | 17.5–25 mg/kg | PO | For enteric amoebas and flagellates: BID for 10 days | |

| NW and OW | 25 mg/kg | PO | For Tritrichomonas mobilensis, Giardia lamblia: BID for 5 days | |

| NW and OW | 30–50 mg/kg | PO | For Balantidium coli: BID for 5–10 days | |

| Moxidectin (Pro Heart) | NW and OW | 0.5 mg/kg | PO; IM | For Strongyloides sp.: give one dose |

| Niclosamide (Yomensan) | NW and OW | 100 mg/kg | PO | For intestinal cestodiasis: give one dose |

| Owl monkey | 150 mg/kg | PO | For intestinal cestodiasis: give one dose | |

| NW | 166 mg/kg | PO | For cestodes, anoplocephalids | |

| Paromomycin (Humatin) | NW and OW | 10–20 mg/kg | PO | For Balantidium coli: BID for 5–10 days |

| NW and OW | 12.5–15 mg/kg | PO | For amoebae: BID for 5–10 days; drug has minimal absorption—need to use additional drugs for invasive disease | |

| For Entamoeba histolytica: BID for 5–10 days | ||||

| Owl monkeys | 25–30 mg/kg | PO | For enteric amoebiasis: BID for 5–10 days | |

| Cercopithecids | 100 mg/kg | PO | SID for 10 days | |

| Praziquantel (Droncit) | NW and OW | 15–20 mg/kg | PO; IM | Treatment for trematodes |

| NW and OW | 40 mg/kg | PO; IM | For Schistosoma sp., other cestodes and trematodes: give once | |

| Primaquine (Primaquine phosphate) | NW and OW | 0.3 mg/kg | PO | For Plasmodium sp.: SID for 14 days; use with chloroquine |

| Pyrantel pamoate (Strongid-T) | NW and OW | 11 mg/kg | PO | For oxyurids: give once and repeat in 10 days Better than thiabendazole for Trypanoxyuris micron in owl monkeys |

| Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) | NW and OW | 10 mg/kg | PO | For Plasmodium sp.: give once daily Monitor for signs of folate acid deficiency and treat if needed |

| Pyrvinium pamoate (Povan) | NW and OW | 5 mg/kg | PO | Give once; repeat every 6 months. |

| Quinacrine (Atabrine) | NW and OW | 2 mg/kg | PO | For Giardia: TID for 5–7 days May cause GI upset in squirrel monkeys |

| NW and OW | 10 mg/kg | PO | For Giardia: TID for 5 days. Is 70%–95% effective | |

| Ronnel (Ectoral) | NW and OW | 55 mg/kg | PO; TP | For lung mites and ectoparasitic mites: give q72h for 4 times and then every 7 days for 3 months topically |

| Sulfadiazine (Sulfadiazine) | NW and OW | 100 mg/kg | PO | For Toxoplasma: treat along with pyrimethamine |

| Sulfadimethoxine (Albon) | NW and OW | 50 mg/kg | PO | For coccidiosis: give one dose; then 25 mg/kg/day |

| Thiabendazole (Thibenzole) | NW and OW | 50 mg/kg | PO | For Strongyloides sp. and hookworms (Necator): SID for 2 days |

| NW and OW | 75–100 mg/kg | PO | Give once and repeat in 21 days | |

| Tinidazole (Tindamax) | Marmosets | 150 mg/kg | PO | For Giardia: SID for one day; then give 77 mg/kg SID for 4 days |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree