Chapter 16

New Techniques in Chelonian Shell Repair

Triage of Shell Trauma

Good Prognosis

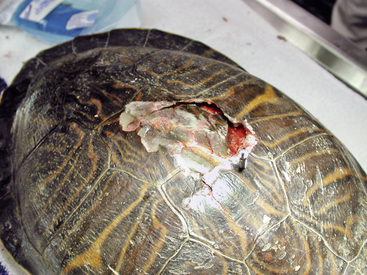

Chelonians seen with multiple fractures, unstable fractures, mild open fractures, or dog bites with shell puncture have a good prognosis with treatment. Open fractures are characterized by malunion of a fracture with the bone exposed to the coelom or missing pieces of the bony carapace or plastron. If large pieces of shell are missing, this diagnosis may be, instead, considered a fair prognosis; however, if no penetration of the underlying soft tissue has occurred, the prognosis is still good. These animals will need supportive care, surgical stabilization, and hospitalization for a few months (Figure 16-1).

Fair Prognosis

Chelonians with multiple fractures involving the shoulder or pelvic area or penetrating punctures of the coelom have a fair prognosis (Figure 16-2). Multiple fractures that destabilize the shoulder or pelvis may lead to ambulation difficulties. If the leg cannot be used at all, this would be a grave prognosis; the prognosis increases favorably as the ability to move the leg increases. If a chelonian can move the leg and still walk or has 75% normal range of motion, it may be worth pursuing treatment. Aquatic turtles may have a little more leeway because a water environment is more forgiving. However, the rehabilitation philosophy of the practitioner should ultimately guide the course of treatment.

Guarded Prognosis

Chelonians with open fractures with punctures to the viscera have a guarded or poor prognosis. In some cases, tortoises may be seen with intestines trailing from the fracture or large amounts of debris, dirt, and fly larva in the fracture site or fractured limbs. These cases are difficult to treat successfully. Resection of bowel is possible; however, it is sometimes difficult to diagnosis the extent of the trauma. Further workup may be warranted, but more severe cases of this type of wound fall into the grave prognosis category.

Grave Prognosis

This group includes chelonians with multiple fractures, internal injuries, head injuries, and, most importantly, fractures incorporating the spine. Spinal injuries are sometimes difficult to assess in tortoises and turtles because of their stoic nature and defensive behaviors. Most spinal injuries in chelonians result in neurologic damage affecting the rear legs. If a fracture can be visualized across the sagittal midline (over the spine) or if the chelonian appears to have neurologic problems, further workup is needed (Figure 16-3). In many cases, even though a fracture may proceed across the spine, it may be difficult to visualize this on radiographs (Figure 16-4). A neuralgic examination, including assessment of sensation and deep pain, may assist in making this diagnosis; however, tortoises are capable of spinal walking, which masks spinal injury. Spinal walking consists of reflexive actions rather than conscious movement. Even if the entire spinal cord is severed, spinal walking is still possible. With spinal injuries, a variety of other problems, such as dennervation of the bladder and lower gastrointestinal tract, are common. In a few of these cases, a tortoise may continue to eat and drink while its urinary bladder and colon enlarges to the point of rupture. If a spinal injury is found, humane euthanasia is suggested. Euthanasia should be completed with euthanasia solution (Beuthanasia-D, Schering-Plough Animal Health, Union, NJ) at 60 to 100 mg/kg. This can be given intravenously, which may prove difficult, or intracoelomically (ICe), which may take up to 12 hours to be completed. An alternative for pet animals is a two-stage euthanasia process, in which the chelonian is anesthetized first and then the euthanasia solution is administered. Intracoelomic injection of barbiturates may adversely affect the histologic features of internal organs.1

FIGURE 16-3 Grave prognosis: transverse fracture of the dorsal carapace in a Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

Triage Treatment

Once the chelonian enters the hospital, it should be evaluated immediately for prognosis, and a decision should be made on moving forward with treatment. Once a prognosis has been assigned, analgesics and supportive care should be started immediately.

Analgesia

Although the field of analgesia has been growing over the last 20 years, reptile analgesia has been lagging severely behind mammalian and avian analgesia.2 Reptiles do not exhibit pain in ways that most veterinarians can recognize; however, it has been shown that many species of reptiles possess antinociception (moving away from a noxious stimulus).3 For many years, the use of butorphanol was extrapolated because it was shown to have analgesic effects in birds.4 However, butorphanol has been shown in iguanas and Red-eared Sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) to not be an effective analgesic.5 Morphine (Baxter Health Care, Deerfield, Ill) (1.5 to 6.5 mg/kg intramuscularly) has produced antinociception in Red-eared Sliders, Freshwater Crocodiles (Crocodylus johnsoni), and Anolis lizards.6–7 Tramadol at 5 mg/kg per os (PO; by mouth), a drug that induces analgesia via both opioid and nonopioid pathways, produced an increase in thermal latency in Red-eared Sliders for 5 days.8 This is a great way of providing postsurgical analgesia with a single dose. Other drugs such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatories such as meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica Inc., St. Joseph, Mo) have been developed for analgesia in mammals and have now been used in reptiles.9 Anecdotal reports that meloxicam is an effective analgesia are widespread. The author has used meloxicam in over 20 species of reptiles at 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 4 to 10 days with positive results. Necropsies by the author on reptiles treated with meloxicam have not shown any secondary kidney effects seen with long-term use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in other species but should be considered a complication of treatment.

Fluid Therapy

Most injured chelonians should be considered to be dehydrated from loss of bodily fluids and or lack of fluid intake. This would place them in the mild (<5%) to moderately (7%) dehydrated category.10 It may be difficult to assess skin tenting in chelonians; however, sunken eyes and changes in packed cell volume (PCV) may be signs of dehydration and and/or blood loss. Reptiles, more so than mammals, can withstand large variations in fluid levels and have developed a larger intracellular fluid volume (48% to 80%) versus extracellular fluid volume (20% to 52%); thus they can withstand longer periods of fluid deficits than mammals.10

Nonetheless, fluids should be administered within the first few hours after arrival. For moderate to severe cases of dehydration, parenteral fluid administration is preferred. This can then be followed by oral administration in the days that follow. Fluid maintenance rates for reptiles are less than mammals and range between 10 and 25 mL/kg per day.10 Fluid selection is also controversial, and long-term use of lactated Ringers may lead to hypokalemia.11–12 Other fluids such as 0.45% saline with 2.5% dextrose may assist in expanding the intracellular and extracellular spaces, whereas fluids such as Plasma-Lyte and Normosol (Baxter Health Care, Deerfield, Ill) do not contain lactate and have higher levels of potassium.10–11 In any case, for short-term use (less than 1 week), any of these fluid choices are appropriate and have been used successfully. For chronic disease or longer term administration, please refer to the literature.10–12

Antibiotics

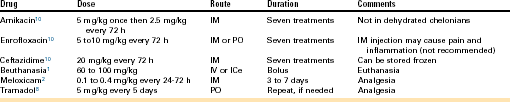

The severity of any wound will dictate the use of antibiotics. In most cases, traumatic shell injury warrants the use of antibiotics. In general, antibiotics with a gram-negative spectrum are preferred for reptiles. Chronic wounds and abscesses will need to have culture and sensitivity testing, and the results will then direct the antibiotic choice. A number of different antibiotics from different drug classes can be used; in this chapter, only a few antibiotics are covered (Table 16-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree