Chapter 16 Neuroophthalmology

Neuroophthalmology should not be a daunting study. If anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the ocular and visual innervation are understood, a diagnosis can be reached through deduction and elimination rather than from memory.

The following cranial nerves are significant in relation to ocular functions:

In addition, significant parts of the CNS are devoted to vision processing and ocular control. Therefore the workup of the neuroophthalmologic patient requires comprehensive neurologic and systemic examinations, in addition to a thorough neuroophthalmologic examination (Table 16-1). This chapter reviews the examination, clinical signs, and diseases of the neuroophthalmologic patient.

Table 16-1 Summary of the Neuroophthalmologic Examination

| TEST OR OBSERVATION | NEUROLOGIC COMPONENTS |

|---|---|

| Menace response | CN II, optic chiasm, optic tract, lateral geniculate nucleus, optic radiation, visual and motor cortex, facial nucleus and nerve cerebellum |

| Size of pupils and reaction to light | CN II, optic chiasm, proximal optic tract, CN III, sympathetic nerves, diencephalon-mesencephalon (pretectal and oculomotor nuclei) |

| Eyelids (size of fissure) | CNs III, VII, sympathetic nerves |

| Third eyelid | Sympathetic nerves |

| Position of eyes | CNs III, IV, VI, vestibular system, brainstem |

| Normal and abnormal nystagmus | CN VIII—brainstem and vestibular system—CNs III, IV, VI |

| Palpebral reflex | CNs V, VII |

CN, Cranial nerve.

ASSESSING VISION AND PUPILLARY LIGHT REFLEXES

Vision and the Menace Response

Vision is initially evaluated as the patient walks into the clinic or examination room. The ability to navigate in these unfamiliar surroundings may reveal visual deficits. A more direct assessment is made by testing the animal’s response to a menacing gesture. The menace response is evoked by making a threatening gesture with the hand at each eye while the other hand covers the opposite eye. If the other eye is not covered, an alert animal that is unilaterally blind in the eye being tested may observe the threat with its normal eye and respond by blinking bilaterally, thus creating a false positive response (i.e., a blink “response” in a blind eye). It is crucial to the validity of this test that the threatening hand does not touch the patient or create enough air currents to be felt by the patient, which may also generate a false positive response (Figure 16-1).

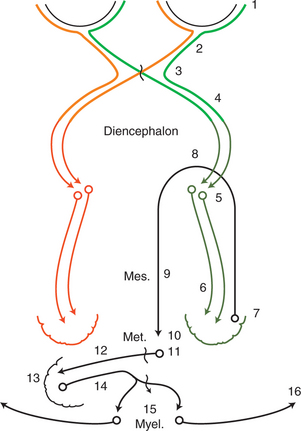

The normal response to this threat is a rapid blink and closure of the palpebral fissure. The anatomic pathways of the afferent and efferent components are depicted in Figure 16-2. The afferent component of the response is relayed by the optic nerve, through the optic chiasm, optic tract, lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), and optic radiation to the visual cortex located in the occipital lobe. It is assumed that the visual cortex projects to the motor cortex, which in turn projects via the internal capsule and crus cerebri to the facial nuclei in the medulla, and from there the facial nerve (CN VII) relays the efferent signal to the eyelid muscles. The complexity of this pathway implies that the resulting blinking is not a reflex but a learned response. Therefore this response may not become fully developed until 10 to 12 weeks of age in some small animals. It is usually present by 5 to 7 days in foals and calves. As a result, menace testing in young patients may result in a false negative result, as the animal does not blink even though it can see.

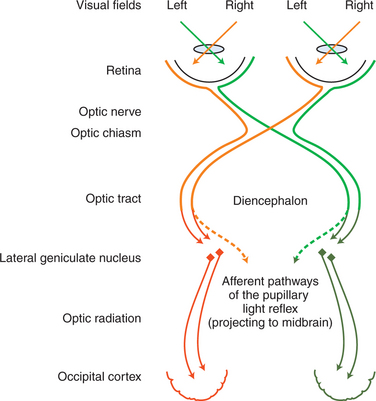

Crossover of optic nerve fibers occurs at the optic chiasm (Figure 16-3). Consequently, the left occipital cortex receives the axons of the lateral retina of the left eye (inputting from the right visual field) as well as the axons of the medial retina of the right eye (inputting, again, from the right visual field) (see orange pathways in Figure 16-3). The right occipital cortex inputs from the left visual fields of both eyes (see green pathways in Figure 16-3). In humans, where 50% of the axons cross over in the chiasm, the left occipital cortex inputs the right visual hemifield of both eyes, and the right occipital cortex inputs the left visual hemifield (orange and green pathways, respectively, in Figure 16-3). In animals, where a greater percentage of fibers cross over, the left occipital cortex will input a greater proportion of the right visual field of the right eye and a smaller proportion of the right visual field of the left eye. Therefore, in humans, a lesion in the left optic radiation or occipital cortex, for example, will cause a loss of the right visual hemifield, with symmetric deficits in both eyes (homonymous hemianopia). In animals, however, such a lesion will cause greater deficits in the visual field of the right eye than those of the left eye. In the dog, where 25% of the fibers remain on the ipsilateral side and 75% of the fibers cross over in the chiasm, a unilateral lesion will cause deficits of 25% and 75% in the visual fields of the ipsilateral and contralateral eye, respectively. In the cat, the respective figures are 33% and 67%. In dogs and cats such visual deficits are difficult to detect as an animal moves in its surroundings. Occasionally, the animal may bump into an object on the side opposite the lesion, but often there is no evidence of visual deficit because 25% to 33% of the visual field is relayed to the unaffected lobe. In horses, sheep, and cattle with 80% to 90% decussation of optic nerve axons there is a greater tendency to walk into objects on the side of the visual deficit, contralateral to the lesion. Theoretically, these deficits could be tested separately by threats from the lateral and medial visual fields. However, this approach is unreliable, and in all domestic animals menace reflex is poor or absent on the side contralateral to the lesion.

If the menace response does not occur, the examiner should rule out another potential cause of false negative responses by checking the facial nerve innervation of the orbicularis oculi. It is possible that the patient is visual but cannot blink due to facial nerve paralysis. This is checked by touching the lateral and medial canthi of the eyelids to test the palpebral reflex, which is expressed as a blink in response to the tactile stimulation. Another way to rule out a false negative response caused by facial nerve paralysis is to carefully watch the eye while performing the menace test. If a facial nerve paralysis exists, forehead or eye retraction is observed when that eye is threatened, but no blinking is observed. With slight retraction of the eye, the third eyelid passively protrudes. A patient with a facial nerve paralysis may therefore have “flashing third eyelid,” which is an indication that vision is intact. If there is no facial nerve paralysis and no menace response occurs, the animal should be lightly struck two or three times with the threatening hand, and then the threat should be repeated without touching the patient. This procedure often arouses and directs the attention of the patient and is then followed by a normal response. Significant cerebellar disease may also cause lack of menace response in a visual animal, as pathways from the visual cortex to the facial nucleus likely run through the cerebellum (see Figure 16-2).

Visual Placing Postural Reaction

In the visual placing postural reaction test, the animal is held off the ground and brought to a table edge. If it sees the table, it elevates its limbs to place them on the table’s surface before the limbs touch the table. A blind animal does not elevate the limbs until they touch the table’s edge (Figure 16-4).

Pupillary Light Reflex

The Anatomic Basis of the Pupillary Light Reflex

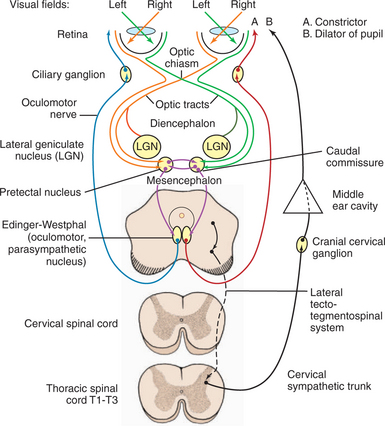

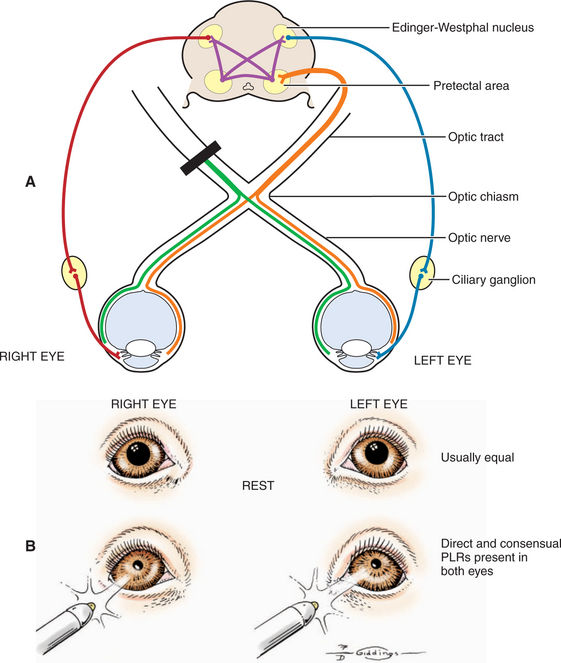

The afferent and efferent pathways controlling pupil size and reaction are depicted in Figure 16-5. The size of the pupil at rest represents a balance between two anatagonistic forces: (1) the amount of incident light stimulating the retina and influencing the oculomotor neurons to constrict the pupil (parasympathetic innervation through CN III), and (2) the emotional status of the patient (e.g., fear, anger, or excitement), which influences the sympathetic system and causes pupillary dilation. In the resting pupil, both pupillary dilator (sympathetic) and the antagonistic pupillary sphincter (parasympathetic) muscles are active. The relative resting parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation and resulting muscle tone determine the size of the pupil (see Figure 16-5, efferent pathways A and B, respectively). The pupillary sphincter (or constrictor) is the more powerful of the two muscles.

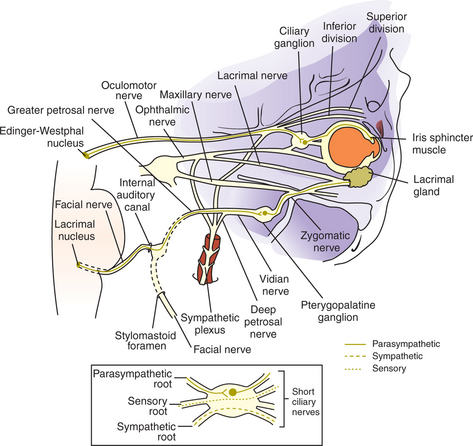

As noted, pupillary constriction and pupillary light reflex (PLR) are controlled by the parasympathetic system. The afferent pathway to the parasympathetic oculomotor nucleus is via the optic nerve to the optic chiasm (where some crossing occurs), through both optic tracts, over the LGNs without forming a synapse, and ventrally into the region between the thalamus and the rostral colliculus, called the pretectal area. Synapse takes place in the pretectal nuclei in the mesencephalon (see Figure 16-5). Crossing between sides occurs between the pretectal nuclei via the caudal commissure. Axons of the pretectal cell bodies pass to the Edinger-Westphal (parasympathetic oculomotor) nucleus of both sides. The parasympathetic axons leave the mesencephalon with the motor axons of CN III (that control four of the extraocular muscles and the levator palpebral muscle), and enter the orbit through the orbital fissure. The ciliary ganglion is located at the rostral end of the oculomotor nerve, ventral to the optic nerve (see figure 16-5 and 16-6). Preganglionic parasympathetic axons of the oculomotor nerve synapse here with the cell bodies of the postganglionic axons. The postganglionic axons pass via short ciliary nerves, enter the globe adjacent to the optic nerve, and innervate the ciliary body and pupillary constrictor muscles. The feline eye has only two short ciliary nerves, each serving half of the iris. A partial parasympathetic lesion may therefore cause a hemidilated pupil (partial internal ophthalmoplegia) in the cat.

Testing the Pupillary Light Reflex

Next, the reaction to strong light is tested. Because of the crossover in the optic chiasm and mesencephalon (see Figure 16-5), stimulation of the retina of one eye with a bright source of light causes constriction of both pupils. First the examiner evaluates the direct PLR by shining a bright light into one eye while observing the reaction of its pupil. To evaluate the indirect PLR, the examiner shines a bright light into one eye while observing the reaction of the contralateral pupil. The patient should be relaxed for this part of the examination, because circulating epinephrines and sympathetic stimulation may interfere with the PLR.

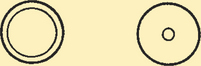

Swinging Flashlight Test

A swinging flashlight test is used by some clinicians. In a normal animal, a quick redirection of a flashlight from one eye to the other (by swinging it from side to side) should reveal semiconstriction of the second pupil. The second pupil initially underwent limited constriction owing to the consensual stimulus from the first eye; swinging the flashlight causes further constriction, because now the second eye is stimulated directly. On the other hand, if a retinal or optic nerve disease is present in the second eye, swinging the flashlight to this eye will result in a dilatation of its pupil. This is because the second pupil initially underwent limited constriction owing to the consensual stimulation from the first eye; however, when the light is moved to the diseased eye, it dilates as it receives no direct stimulation. This quick dilation of the second pupil, called a positive swinging flashlight test result or presence of the Marcus Gunn sign, is considered pathognomonic for a prechiasmal lesion.

Dazzle Reflex

If the PLR cannot be evaluated (e.g., due to severe corneal edema or hyphema), the dazzle reflex is also often helpful in lesion localization. Shining a bright light into the eye elicits a subcortically mediated, reflex rapid eye blink (Figure 16-7). Because this is a subcortical reflex, it may be present in a blind animal. This response involves CN II, the rostral colliculus, and CN VII. Therefore it will be present in an animal blinded by a cerebrocortical lesion but absent in a patient blinded by subcortical diseases.

Electrophysiology

Retinal function can also be evaluated electrophysiologically, using electroretinography to record the responses of the retina to light stimulation. The test is described in detail in Chapter 15. It may be used to determine whether blindness is caused by retinal or postretinal disease. Placing the active electrode over the visual cortex, rather than on the cornea, allows for the recording of visual evoked potentials, which are useful in determining cortical function and vision.

LESIONS IN PATIENTS WITH VISUAL AND PUPILLARY LIGHT REFLEX DEFICITS

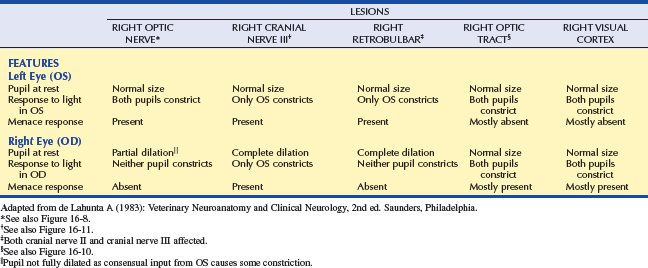

This simple categorization is the first step in localizing the pathologic lesion(Table 16-2 and Figures 16-8 to 16-12). It assumes that ophthalmic examination did not reveal any pathology that would prevent light from reaching the retina (e.g., hyphema, cataract).

Lesions in Blind Patients with Normal Pupillary Light Reflexes

Based on the anatomy of the PLR pathway, the size of the pupils and their response to light are normal in blind animals with disease limited to the distal optic tract (after the afferent PLR fibers have diverged), LGN, optic radiations, and/or visual cortex (see dark green and dark orange pathways, Figures 16-2 and 16-3).

Lesions in Blind Patients with Abnormal Pupillary Light Reflexes

As can be seen in Figures 16-2, 16-3, and 16-5, the afferent fibers of the PLR and visual signal run together from the retina through the optic nerve, optic chiasm, and proximal optic tract, diverging just before the LGN (see light green and light orange pathways in these figures). Minor lesions in this common pathway (e.g., early retinal degeneration) may cause visual deficits without affecting the PLR. This is because, as noted earlier, the PLR is resistant to deficits in afferent input. Therefore if a lesion in this common pathway is significant enough to cause a pupillary abnormality, it usually also causes blindness. Converesely, if the eye is blind due to an afferent lesion, the PLR is almost always abnormal (though not necessarily absent). As a rule, afferent lesions that interrupt this pathway occur in the retina, optic nerve, or optic chiasm (see Figures 16-8 and 16-9). Rarely both proximal optic tracts are affected sufficiently to cause pupillary abnormalities, because the tracts are spread out over a relatively large area. A single optic tract lesion is rare and may cause no PLR abnormality (due to the crossover in the pretectal and oculomotor nuclei) (see Figure 16-10).

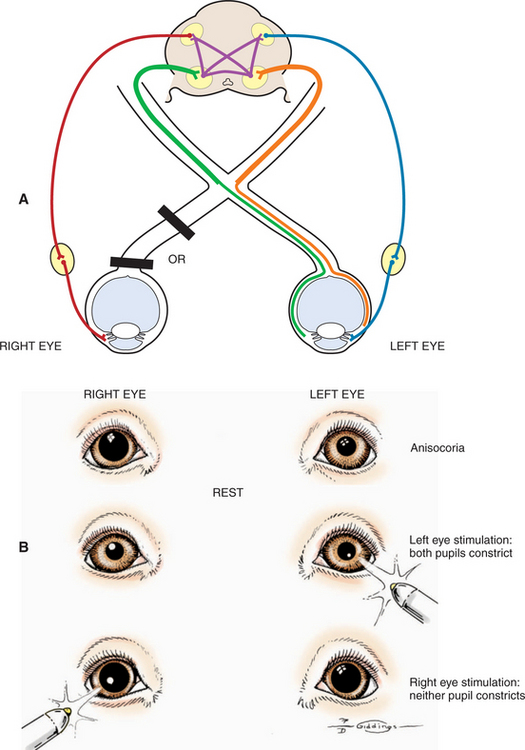

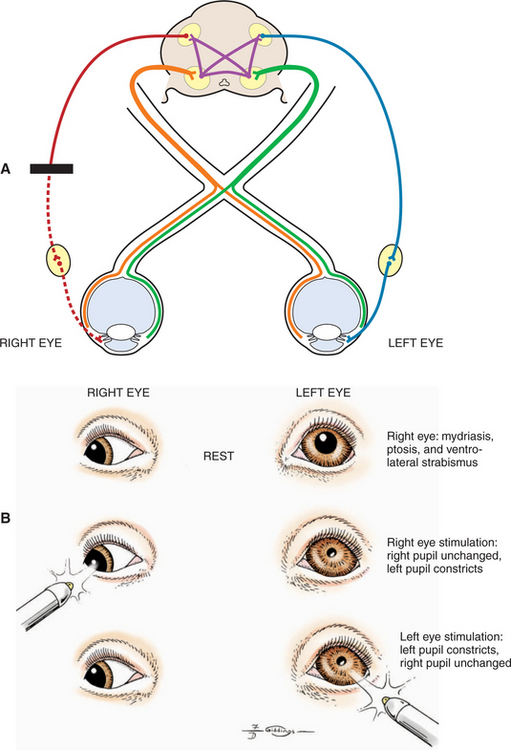

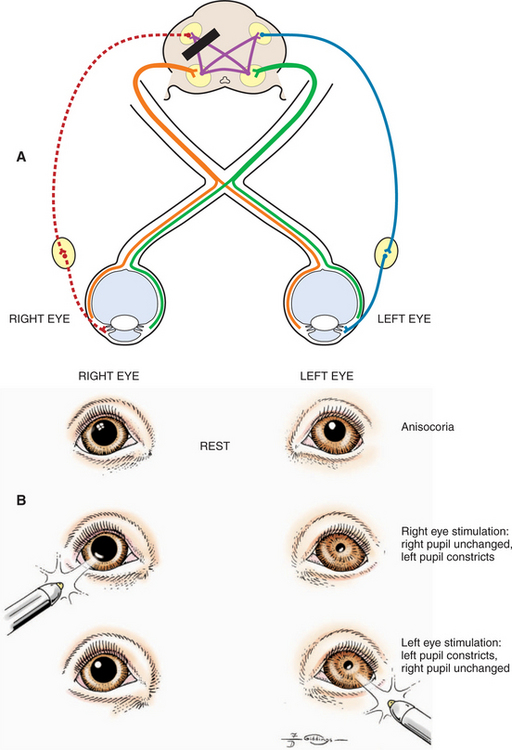

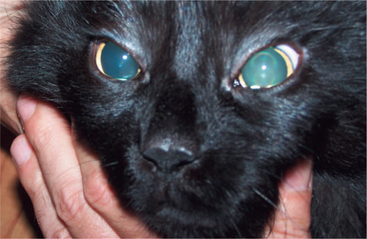

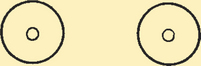

A patient with a unilateral lesion in the retina or optic nerve has no menace response in that eye. The pupil in that eye may be slightly larger (because it receives no direct parasympathetic stimulation from incident light), although it is not fully dilated (due to the indirect stimulation from the unaffected eye) (Figure 16-13). Light directed into the affected eye causes no response in either eye. Light directed into the unaffected eye elicits a bilateral response (see Figure 16-8). To assess direct and indirect responses, the examiner moves the light back and forth between the eyes. In an animal with a unilateral lesion, as the light is directed from the unaffected eye to the affected eye, the pupil in the affected eye dilates back to the resting state created by the room light (indirectly, through the unaffected eye). This is because the strong light source was taken away from the unaffected eye (thereby removing the indirect stimulation) and the lesion in the affected eye has interrupted the direct afferent pathway for this reflex. This phenomenon is readily apparent as the light is repeatedly moved between the eyes. Further confirmation of a unilateral lesion is made by covering the normal eye and observing further dilation of the pupil in the affected eye which is no longer stimulated indirectly by room light through the normal, covered eye.

Figure 16-13 Unilateral mydriasis due to an old trauma that caused sectioning of the left optic nerve.

Common causes of unilateral lesions resulting in PLR and visual deficits include retinal detachment, glaucoma, and retrobulbar abscess or neoplasia. Trauma to the optic nerve is another common cause of unilateral lesions. The trauma may cause direct avulsion of the axons at the level of the optic canals or interference with the vascular supply of the intracanalicular part of the optic nerve. This problem may be more common in horses and in brachycephalic dogs. Ophthalmoscopic examination often shows optic disc atrophy, with secondary retinal degeneration.

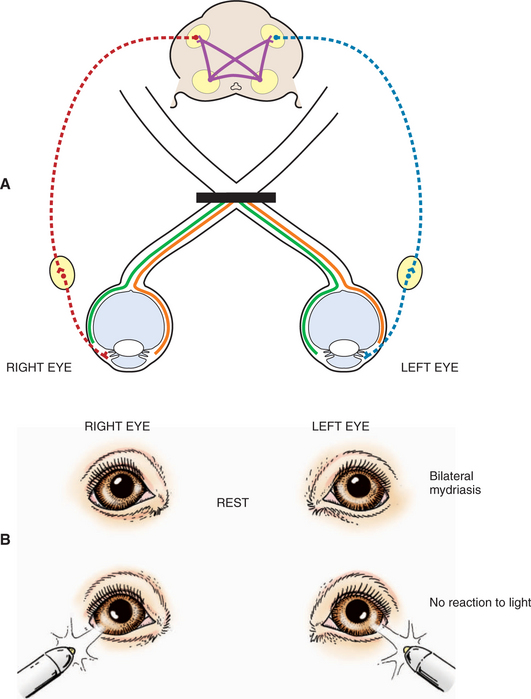

Severe bilateral retinal, optic nerve, or optic chiasm lesions cause blindness with dilated pupils that are unresponsive to light (see Figure 16-9). Bilateral retinal diseases include retinal detachment, end-stage retinal degeneration, SARD, and glaucoma. The most common optic nerve disease to affect vision and PLR is optic neuritis. The disease may be infective (e.g., distemper, cryptococcosis, toxoplasmosis) or inflammatory (GME) though it is frequently idiopathic in nature. It can affect both optic nerves and the optic chiasm, and the patient presents with blindness and fixed, dilated pupils (optic neuritis is discussed under Diseases of the Optic Nerve). In young cattle, vitamin A deficiency may cause optic nerve compression from stenosis of the optic canals. Rarely in cats does ischemic encephalopathy syndrome result in infarction of the optic chiasm.

A retrobulbar or intracranial lesion that affects both the optic nerve and the parasympathetic part of the oculomotor nerve causes a widely dilated pupil in the ipsilateral eye at rest (see Figures 16-8 and 16-11). Because of CN II involvement there is no menace response from this affected eye, and light directed into the affected eye elicits no response in either eye. Light directed into the unaffected eye causes pupillary constriction only in that eye (due to CN III lesion in the affected eye). In addition to loss of PLR, a complete oculomotor nerve deficit will also cause ventrolateral strabismus and ptosis due to denervation of four extraocular muscles and the levator palpebral muscle. However, lesions that involve only the oculomotor nerve, and do not affect vision, may also occur. These are discussed later (see Lesions Causing Pupillary Light Reflex Abnormalities in Visual Patients).

Pupils in Patients with Intracranial Injury

Pupillary abnormalities are common after intracranial trauma. They may also accompany severe acute brain lesions such as those found in polioencephalomalacia and lead poisoning in ruminants. Evaluation of the size of the pupils is important to the assessment both of the location and extent of brain damage from intracranial injury and to evaluate the response to therapy. Pupil size and prognosis in intracranial injury are shown in Table 16-3.

Table 16-3 Pupillary Reactions in Intracerebral Injury

| CONDITION | PUPIL SIZE | PROGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|

| Unilateral oculomotor nuclear or nerve contusion or compression* | Anisocoria | Guarded |

| ||

| Compression of midbrain tectum† | Bilateral miosis | Guarded |

| ||

| Bilateral oculomotor nuclear or nerve contusion or compression | Bilateral mydriasis | Grave |

|

* Asymmetric interference with cerebral control of oculomotor neurons or the sympathetic upper motor neuron system, or both.

† Bilateral sympathetic upper motor neuron deficiency or release of oculomotor parasympathetic neurons from cerebral inhibition.

Injuries that predominately involve the prosencephalon often result in very miotic pupils. Severe bilateral miosis is a sign of acute, extensive brain disturbance that by itself is not necessarily of any localizing value. The return of the pupils to normal size and response to light is a favorable prognostic sign and indicates recovery from the brain disturbance, especially following trauma. However, progression from bilateral miosis to bilateral mydriasis with fixed pupils that are unresponsive to light in trauma cases indicates that the brain disturbance (e.g., hemorrhage, edema) is advancing and the oculomotor neurons in the midbrain are nonfunctional (Figure 16-14). This progression often accompanies severe contusion of the midbrain with hemorrhage, usually along the midline, which may cause brain swelling and herniation of the occipital lobes ventral to the tentorium cerebelli, accompanied by compression and displacement of the midbrain or oculomotor nerve (or both).

The cause of unilateral or bilateral miotic pupils in acute brain disease is not known. It probably represents facilitation of the oculomotor parasympathetic neurons released from higher-center inhibition owing to its functional disturbance. Pupillary changes may take place hourly after head trauma. Unilateral mydriasis that in some cases may be accompanied by miosis of the other pupil is probably brought about by compression of the ipsilateral oculomotor nerve; the pupils, though anisocoric, may be slightly reactive. Experiments in dogs have shown that compression of the brainstem tectum at the level of the rostral colliculus causes miosis. Compression of CN III produces mydriasis.

Lesions Causing Pupillary Light Reflex Abnormalities in Visual Patients

Abnormalities in pupillary constriction that are not accompanied by visual deficits localize the lesion to the oculomotor nerve after it has exited the mesencephalon. As noted previously, the oculomotor nerve provides (1) somatic efferent inner-vation to the dorsal, medial, and ventral recti muscles, the ventral oblique muscle, and the levator palpebral muscles and (2) parasympathetic innervation to the iridal sphincter. Both functions may be affected by lesions to the nerve. There-fore such a patient will present with three clinical signs (see Figure 16-11):

LESIONS CAUSING STRABISMUS

Function of the Extraocular Muscles

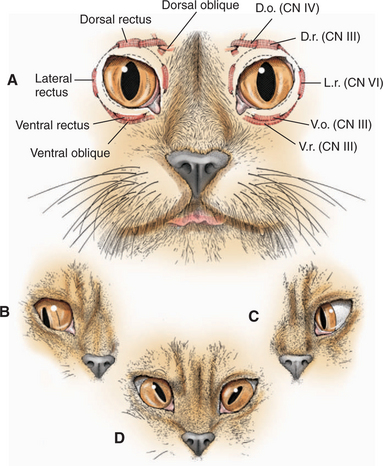

Innervation and action of the extraocular muscles are summarized inFigure 16-15 and Table 16-4. The globe has three axes of rotation, and the muscles are grouped into three opposing pairs. Each muscle in the pair acts in a reciprocal manner with its partner, similar to flexor and extensor muscles in the limbs. Such a pair of extraocular muscles is termed yoke muscles. When the two eyes move in the same direction the movement is called conjugate. Around a horizontal axis, passing transversely through the center of the globe, the medial rectus muscle adducts and the lateral rectus muscle abducts the globe. Around the anterior-posterior axis, through the center of the globe, the dorsal oblique intorts the globe (rotates the dorsal portion medially toward the midline), and the ventral oblique extorts the globe (moves the same point laterally away from the midline). The dorsal and ventral rectus muscles rotate the globe dorsally and ventrally, respectively.

Table 16-4 Extraocular Muscles: Innervations and Actions

| MUSCLE | INNERVATION | ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Superior (dorsal) rectus | Oculomotor (CN III) | Elevates globe (rotates upward) |

| Inferior (ventral) rectus | Oculomotor (CN III) | Depresses globe (rotates downward) |

| Medial rectus | Oculomotor (CN III) | Turns globe nasally (adduction) |

| Lateral rectus | Abducens (CN VI) | Turns globe temporally (abduction) |

| Superior (dorsal) oblique | Trochlear (CN IV) | Intorts globe (rotates 12 o’clock position nasally) |

| Inferior (ventral) oblique | Oculomotor (CN III) | Extorts globe (rotates 12 o’clock position temporally) |

| Retractor bulbi | Abducens (CN VI) | Retracts globe |

CN, Cranial nerve.

Lesions Causing Strabismus

Strabismus due to Lesions in Innervation of the Extraocular Muscles

OCULOMOTOR PARALYSIS.

Lesions of the oculomotor nucleus, or oculomotor nerve lesions, cause a lateral and slightly ventral strabismus— exotropia—primarily from loss of innervation of the medial rectus and secondarily from the denervation of the dorsal and ventral recti muscles and the ventral oblique muscle (see Figures 16-11 and 16-15, B). There is experimental evidence to support the direction of this strabismus, although it is difficult to explain the ventral deviation on the basis of the anatomy of the oblique muscle. Due to the lesion, eye adduction is deficient due to denervation of the medial rectus muscle. This can be observed on testing of normal vestibular nystagmus: As the head is moved in a dorsal plane, side to side, the eyes normally develop a jerk nystagmus with the quick phase in the direction of the head movement. The jerklike movement toward the nose is adduction resulting from contraction of the medial rectus innervated by the oculomotor nerve (CN III). This adduction, as well as lid opening and pupillary constriction, will be reduced by lesions to CN III.

Exotropia may also be seen in hydrocephalic animals that have an enlarged cranial cavity. Both eyes often deviate ventrolaterally, and therefore the syndrome is called sunset eyes. This abnormality is thought to result from a malformation of the orbit that occurs when the cranial cavity is distorted by the early development of the brain abnormality. The eyes adduct and abduct normally on testing of normal vestibular nystagmus, and no ptosis or pupillary abnormality is present. Therefore this exotropia is not related to oculomotor dysfunction.

ABDUCENT PARALYSIS.

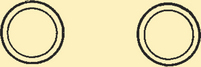

Lesions of the abducent nucleus or nerve cause paralysis (palsy) of the lateral rectus and retractor bulbi muscles. Paralysis of the retractor bulbi muscle prevents the eye from retracting in response to a threatening gesture. This can be tested by performing the menace test while holding the upper eyelid open. Globe retraction and the resulting third eyelid elevation may be observed in a normal animal. Paralysis of the lateral rectus muscle causes unilateral esotropia (medial strabismus), resulting in asymmetry (see Figure 16-15, C). Compared with the normal eye, the affected eye cannot be abducted fully. The clinician can detect this difference by moving the patient’s head from side to side in a horizontal plane and observing the extent of abduction and adduction of each eye.

TROCHLEAR PARALYSIS.

Lesions of the trochlear nucleus or nerve paralyze the dorsal oblique muscle, causing dorsolateral strabismus. In species with a round pupil, such as the dog, it is difficult to detect this type of strabismus; however, ophthalmoscopic examination may show that the superior retinal vein is deviated laterally from its normal vertical position because of the abnormal rotation caused by the tone in the unopposed ventral oblique muscle. In cats, which have vertical pupils, the dorsal aspect of the pupil deviates laterally with a lesion of the trochlear neurons (see Figure 16-15, D). In cattle and sheep, which have horizontal pupils, the medial portion of the pupil is deviated dorsally (Figure 16-16). Trochlear nerve (CN IV) lesions are rare. This abnormality is seen in polioencephalomalacia in ruminants and is thought to represent a unique susceptibility of the trochlear neurons to this metabolic encephalopathy.

LESIONS CAUSING EYELID ABnoRMALITIES

Third Eyelid Abnormalities

Protrusion of the Third Eyelid

Protrusion of the third eyelid is a typical feature of the following diseases:

HORNER’S SYNDROME.

A constant partial protrusion of the third eyelid occurs in Horner’s syndrome because of loss of the sympathetic innervation of the smooth muscle that normally keeps it retracted (Figure 16-17). The syndrome is discussed separately later in this chapter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree