Neurological and Locomotor Disorders

10.1 Investigation of neurological and locomotor disorders

Neurological signs are common in rabbits. They may be caused by primary diseases of the central nervous system such as encephalitozoonosis or they may be secondary to some systemic problem such as keto-acidosis or hypokalaemia. Many diseases cause neurological signs, such as ataxia or seizures, in their terminal stages. Spinal deformities and associated neurological problems are also common in pet rabbits. Diseases of the central nervous system or locomotor system may be manifested by skin disease, digestive disorders or urinary tract problems. Therefore, a detailed clinical history and thorough examination are vital in determining the cause of neurological and locomotor disorders.

10.2 Lameness

Observation of a rabbit’s gait can be very informative. It is worthwhile letting a rabbit move around the consulting room prior to performing a clinical examination. Owners are often unaware that their pet has difficulty moving. They may not be familiar with normal rabbit locomotion or may not actually see their rabbit hopping about because it spends most of its life confined to a hutch. The rabbit can be placed on the floor to observe its gait. Obviously, the owner and the vet must be confident that the rabbit can be caught again if it is allowed to have the freedom of the consulting room. Many rabbits dislike smooth flooring and benefit from a towel placed on the floor for them to hop over. Neurologically normal rabbits will hop even at slow speeds, whereas rabbits with subtle neurological abnormalities will often walk. Severe abnormalities of gait may be detected. Inspection and palpation of the limbs may reveal bony enlargements, swollen joints, abscesses or even fractures that have not been detected by the owner. Some causes of lameness in rabbits are listed in Box 10.1. Treatment of abscesses is described in Section 6.3.

Ulcerative pododermatitis is a common cause of lameness and interferes with normal stance and gait (see Section 7.10). In advanced cases, the superficial flexor tendon becomes displaced, giving a ‘dropped hock’ appearance that can be mistaken for spinal cord disease (see Figure 7.9).

A case of hypertrophic osteopathy has been reported in a rabbit (DeSanto, 1997). The rabbit was presented with swollen hind legs that were painful on examination. Radiological examination revealed periosteal proliferation of the distal half of the tibia and tarsometatarsus. The hypertrophic osteopathy was secondary to a thoracic tumour that was a metastasized uterine adenocarcinoma.

10.2.1 Orthopaedic surgery

It is beyond the scope of this book to describe every orthopaedic procedure that may be necessary for pet rabbits. The same basic principles apply to rabbits as to cats. For fractured limbs, the aim of orthopaedic intervention is to restore anatomical alignment and immobilize the fracture site to permit rapid healing. Although splinting the limb may appear to be the simplest option, the shape of rabbits’ legs does not lend itself to the easy application of satisfactory splints, slings or bandages, so, in many cases, surgery is indicated. Internal fixation usually involves pinning rather than plating, due to the small bones and thin cortices. Rabbit bones are brittle and fractures are often complex with multiple fragments. On the positive side, rabbit bone heals quickly. External fixation is often the solution for fracture repair in rabbits. The effects of external fixation on bone have been studied in laboratory rabbits. In an investigation of bone loss due to immobilization with an external fixator, no significant changes in bone strength, stiffness or mineral content were found after 6 weeks, but bone strength was reduced by 87% and mineral content by 90% after 12 weeks. These effects were less pronounced using an external fixator rather than using metal plates (Terjesen and Benum, 1983).

10.2.2 Amputation

Amputation of a fractured limb offers an economic solution for a complex fracture and may be the only option for an intractable condition such as septic arthritis or neoplasia. Rabbits tolerate amputation well, especially of a forelimb. The procedure is similar to other species. The bone should be sectioned with a saw, rather than bone cutters, as it is liable to shatter. The main drawback of amputation, especially of a hindlimb, is the effect on the contralateral leg. There is a risk of avascular necrosis of the skin on the plantar aspect of the metatarsus (ulcerative pododermatitis, sore hocks) due to increased pressure (see Section 7.10). The risk can be reduced by preventing obesity, encouraging activity and housing the rabbit on clean, dry, compliant bedding. With forelimb amputation the rabbit may experience difficulty grooming that side of the head, ear and face. The owner or a bonded companion may need to assist in performing these actions.

10.3 Neurological diseases

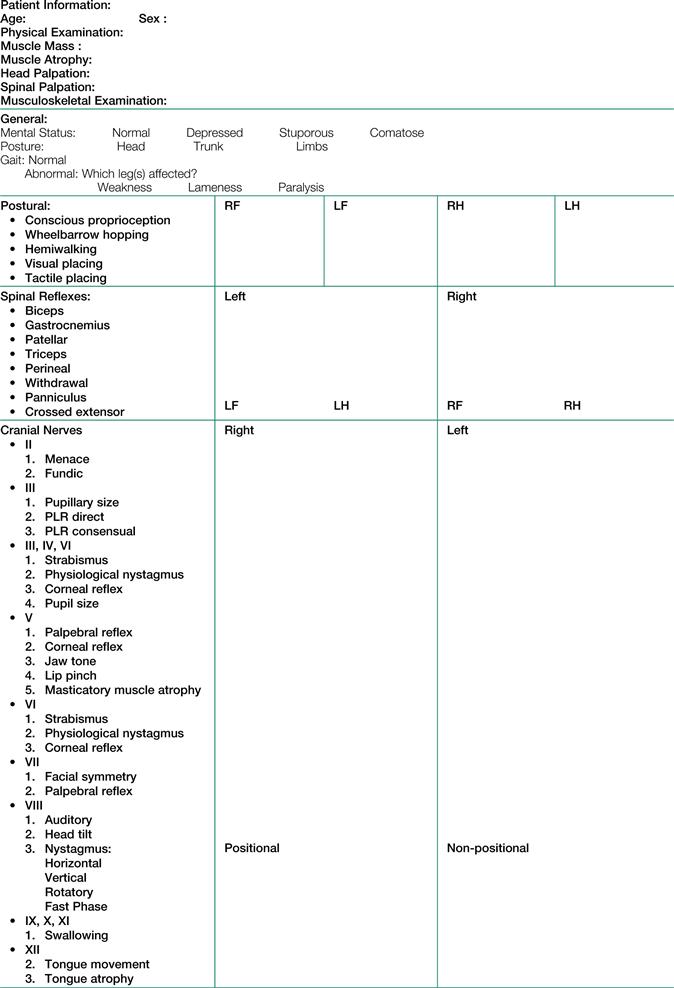

A detailed neurological examination is difficult in rabbits but proprioreceptive deficits, paresis or paralysis are easily detectable: see Figure 10.1 for a detailed neurological examination form. There are many external signs that suggest neurological disease on initial visual inspection. Rabbits perform contortions in order to groom thoroughly (Figure 10.2). The coat and perineum may show evidence of lack of grooming or perineal dermatitis that are indicative of spinal disease or other neurological problems. Cheyletiellosis and matted fur suggest reduced flexibility. There may be pain associated with palpation of the spine or there may be a history of aggression.

Figure 10.2 (A-C) Healthy rabbits performing normal grooming routines.

It is clear that balance and coordination are essential for performing even the most basic normal behaviours. Image courtesy of Heather Pinchien.

A neurological examination should be attempted once a general physical examination has been completed. Rabbits as prey animals have a diminished menace reflex and may not respond to painful stimuli in the expected way as part of a freeze response. Other than these differences, the reflexes may be assessed in the same manner as other species. Generally the neurological examination should start with tests/regions unlikely to cause pain or distress or require significant handling. The aim of the neurological exam is to evaluate both sensory and motor functions in response to external stimuli. This will confirm the location of altered function within the nervous system. Clinical signs due to loss of nervous system function will be similar, regardless of the type of lesion that has caused them. Once the abnormality is located, then further testing can be logically planned. For example, CT would be very helpful in the diagnosis and treatment planning of peripheral vestibular disease caused by pasteurellosis, whereas MRI would be indicated for confirmation of central vestibular disease caused by encephalitozoonosis.

Laboratory investigations are helpful. Haematology may show evidence of chronic infection in the form of leucocytosis, neutrophilia or monocytosis, although absence of these changes does not negate the possibility of an abscess or chronic inflammation (see Section 2.2). Biochemical assays, especially serum potassium and glucose, are informative. Liver and kidney function tests can show evidence of metabolic causes of neurological symptoms. Cisternal puncture for cerebrospinal fluid collection and myelography is feasible and follows the same principles as for a dog or cat. As in the dog, cisternal puncture is easier than lumbar puncture.

Radiography is essential for cases of paresis or paralysis. Bony abnormalities of the spinal column, such as fractures, subluxations or spondylosis, may be seen. There may be evidence of underlying oste-penia. Incidental findings such as urolithiasis or evidence of gastrointestinal hypomotility are significant. Skull radiography can be used to investigate vestibular disease and the tympanic bullae can clearly be seen on a dorsoventral view (see Figure 11.4).

Advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly being used in the investigation of locomotor and neurological disorders, and many referral centres are now imaging significant numbers of rabbits. CT scanning has revolutionized the understanding of middle ear disease in the rabbit, while MRI has enhanced the veterinary surgeon’s ability to diagnose intracranial lesions causing neurological signs. CT is also very useful for the diagnosis of subtle joint and spinal abnormalities that may contribute to lameness or apparent neurological signs.

10.4 Encephalitozoon cuniculi

Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidian parasite that affects a wide range of species. A detailed description of the disease and its treatment is given in Section 14.4.2.5 and the clinical manifestations are summarized in Box 10.2. Encephalitozoonosis is widespread in rabbits (52% of UK rabbits showed serological evidence of exposure in a survey performed by Keeble and Shaw, 2009). Encephalitozooonosis causes granulomatous lesions in the brain and kidney. Focal necrosis gives the kidney a characteristic pitted appearance (see Section 12.5.1 and Figure 14.5). Encephalitozoon cuniculi can also cause phacoclastic uveitis (see Section 9.7.3.1). Clinical manifestations of E. cuniculi range from inapparent to mild renal insufficiency to neurological disaster. Infection can be latent and may never manifest itself clinically. The parasite is endemic in many rabbit colonies. Commercial laboratories serologically screen their stock for E. cuniculi and cull affected animals. The most commonly recognized clinical manifestation is vestibular disease. Transmission of the parasite takes place via urine infected with spores. The spores invade the cells of the intestinal mucosa where they multiply and invade the reticuloendothelial system, which distributes the parasite throughout the body. The organism eventually localizes in the brain and kidney, and occasionally the myocardium. In the kidney, E. cuniculi can be found in the tubular epithelial cells and spores are flushed out in the urine. Cross-infection can take place between rabbits and rodents.

10.4.1 Central nervous system (CNS) signs attributed to Encephalitozoon cuniculi

CNS signs relate to granulomatous encephalitis and include sudden death, seizures, ataxia, torticollis, paresis or paralysis. Signs develop rapidly when brain cells rupture to release parasites into surrounding tissues. Milder neurological symptoms also occur which may be noticed by observant owners. Some rabbits have nystagmus or sway slightly when they are at rest. Others are ataxic or appear clumsy. Deafness and behavioural changes have been recognized in seropositive animals. Incontinence, polydypsia and polyuria can also be associated with E. cuniculi infection, although it is not clear whether this is a behavioural consequence of central lesions or due to mild renal insufficiency. The most commonly recognized neurological sign is vestibular disease that can range in severity from a minor head tilt to an animal that is unable to right itself and is rolling and hemiparetic (Figures 10.3–10.5).

Figure 10.4 Moderate head tilt in a female neutered rabbit with suspected clinical encephalitozoonosis.

Figure 10.5 Severe head tilt with rolling in a 1-year-old male neutered rex rabbit.

When unstressed, this rabbit was able to maintain his head position, self-feed and also self-groom. His mobility was restricted; however, he was mobile enough to prehend caecotrophs.

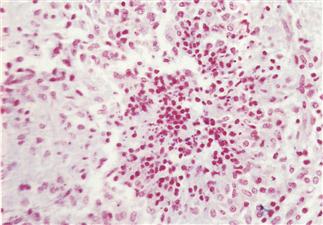

Lesions do not develop in the central nervous system until at least 30 days after infection. Changes are those of a focal non-suppurative granulomatous meningo-encephalomyelitis, with astrogliosis and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration (Percy and Barthold, 1993). Granulomas are characterized by a central area of necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, microglia, epitheloid cells and sometimes giant cells (see Figure 10.6). In other instances, only dense accumulations of glial cells are noted. In the brain, there appears to be no predilection sites and granulomas are randomly distributed throughout all areas. Lesions can be found in the cerebellum and spinal cord. In many instances the organism cannot be identified in chronic lesions but is seen in large numbers in distended cells with no detectable inflammatory response (Pakes and Gerrity, 1994).

Figure 10.6 Granulomatous encephalitis caused by Encephalitozoon cuniculi.

A section of brain taken from an immature mixed breed female rabbit that suddenly developed seizures and became blind is shown. The rabbit died. Histologically, there was moderate disseminated granulomatous encephalitis throughout the brain with lymphoplasmacytic perivascular cuffing and meningitis. The granuloma illustrated consists of a defined collection of histiocytes, occasional multinucleated cells and peripherally located lymphocytes and plasma cells. Small numbers of Gram-positive spherical E. cuniculi spores can be seen in cells within the granuloma. (Photograph supplied by Malcolm Silkstone, Abbey Veterinary Services, Newton Abbot.)

10.4.2 Vestibular disease

Vestibular disease in rabbits may be referred to as wry neck, torticollis, otitis media or interna, laby-rynthitis or head tilt. A list of differential diagnoses includes neoplasia, abscesses, trauma, vascular disease, toxoplasmosis and other non-specific causes of neurological disease (see Table 1.7). Vestibular disease is the most frequently recognized manifestation of E. cuniculi in pet rabbits. Pasteurellosis is the main differential diagnosis. The vestibular system is responsible for maintaining posture in relation to gravity, and for the movements of the eyes in relation to the position of the head. The peripheral vestibular system is composed of the labyrinth, the vestibular ganglion and the vestibular branch of the VIIIth cranial nerve. The labyrinth is situated in the inner ear surrounded by the petrous temporal bone. The vestibular nerve runs through the internal acoustic meatus into the cranial cavity and enters the rostral medulla at the cerebromedullary angle. Axons of the vestibular nerve terminate in the vestibular nuclei in the medulla or the cerebellum. Central vestibular disease results from lesions in the brainstem, whereas peripheral vestibular disease is due to lesions in the cochlea and vestibular apparatus in the inner ear or along the vestibular nerve.

In the USA, cerebral larval migrans by the larva of the ascarid Baylisascaris can cause torticollis. The parasite is ingested with food that has been contaminated by raccoon faeces. It is a problem associated with feeding hay. Baylisascaris does not occur in the UK. In pet rabbits in the UK, the two main causes of vestibular disease are pasteurellosis and E. cuniculi infection. Ascending Pasteurella multocida infection can spread from the nasal cavity to the middle ear along the eustachian tube to the inner ear and vestibular tract. In some cases, brain abscesses are found along the vestibular tract. Both diseases can occur simultaneously, particularly since encephalitozoonosis depresses immune function.

Kunstyr and Naumann (1983) compared the incidence of encephalitozoonosis and pasteurellosis as a cause of head tilt in dwarf and non-dwarf breeds of rabbits. The dwarf rabbits were pet animals and the non-dwarf group consisted of laboratory rabbits. All cases were euthanized when they developed torticollis. Outer and middle ears were examined for the presence of pus or ear mites, and inner organs and the brain were examined histologically. The non-dwarf laboratory rabbits had otitis interna and empyaema. Pasteurella multocida was isolated from the pus and mucous membranes. With one exception, none of the group of pet rabbits showed signs of otitis, but they all had kidney and brain lesions characteristic of encephalitozoonosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree