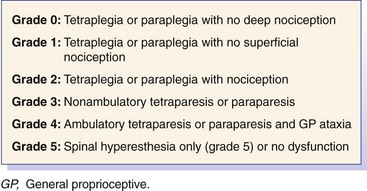

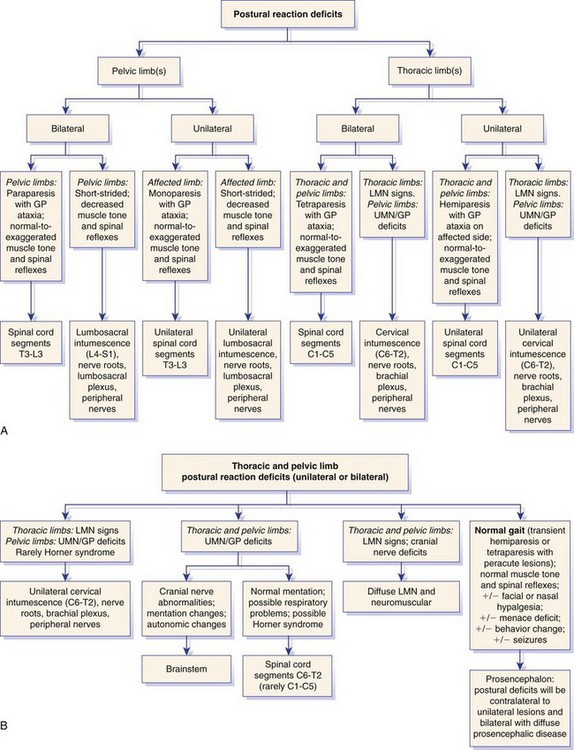

Chapter 26 A precise neuroanatomic diagnosis is essential for the generation of an appropriate differential diagnosis. Furthermore, the correct differential diagnosis allows the clinician to interpret neurodiagnostic tests with greater accuracy. This chapter is meant to provide the clinician with the basic functional neuroanatomy and clinical examination skills necessary to make an accurate neuroanatomic diagnosis. It is modeled heavily on the examination recommended by deLahunta.2 Some clinicians utilize a grading scheme for spinal cord lesions to help prognosticate and to monitor response to treatment. Such grading schemes evaluate gait with respect to strength, proprioception, and sensory function. Grading schemes typically are based on a scale from 0 to 5, but use of this scale is somewhat inconsistent in the literature; some studies or references utilize grade 0 as normal, whereas others utilize grade 5 as normal. If a grading scheme is utilized, clinicians should qualify the grade with descriptors of strength, proprioception, and sensory function to avoid confusion. For spinal cord lesions, the degree of dysfunction recently has been classified using a modified Frankel score (Figure 26-1).4,6 Normal postural reactions require that all major sensory (general proprioceptive) and motor (upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron) components of the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system be intact. Although many clinicians use postural reactions to assess conscious proprioception, this is a misnomer because all postural reactions rely on both motor and proprioceptive systems. Furthermore, when postural reactions are assessed, both conscious (proprioceptive pathways projecting to the contralateral somesthetic [sensory] cerebral cortex) and unconscious (proprioceptive pathways projecting to the cerebellum) proprioceptive pathways are tested; deficiencies in these two key components of the general proprioceptive system cannot be separated practically from one another.2 The clinician should be cautious when interpreting postural reaction deficits because they are not of specific localizing value when performed without the other components of the neurologic examination (Figure 26-2). For example, both a recumbent patient with a severe and diffuse neuromuscular disorder and a patient with a severe cervical spinal cord lesion may have delayed (to absent) postural reactions in all four limbs. Close assessment of muscle mass, muscle tone, and spinal reflexes is necessary to differentiate between these two localizations. Hopping: While the pelvic limbs are supported and with the examiner standing over the animal, the patient is faced away from the examiner and is hopped on one thoracic limb, while the other thoracic limb is held off the ground. The patient should be moved laterally over the limb that is being tested; the strength and coordination of the limbs should be observed in comparison with one another. The clinician should observe the lateral aspect of the thoracic limb being tested; the limb should move (hop) as soon as the shoulder is moved laterally over the paw. Any delay, irregularity, or exaggeration in this response is abnormal. Extensor Postural Thrust: Although this test is performed only occasionally, it may be helpful in patients with subtle pelvic limb signs. The patient should be held off the ground and supported caudal to the thoracic limbs, then lowered to the ground with the pelvic limbs placed slightly in front of the patient. The normal reaction is for the patient to “walk” with its limbs underneath the body to support its weight. A delay in limb movement or failing to place the limb directly under the body to support weight is considered a deficit. Moving the patient forward and backward tests the symmetry of pelvic limb strength and coordination. Often, extensor postural thrust testing is helpful in evaluating cats. Hemiwalking: This postural reaction is not performed routinely. On one side of the body, the thoracic and pelvic limbs should be held off the ground, and the patient should be forced to walk forward or to the side. The patient should hop smoothly on both thoracic and pelvic limbs, but interpretation can be difficult; additionally, this test poses a risk to larger patients, which may fall and exacerbate underlying injury. Wheelbarrowing: This postural reaction is performed occasionally and may be helpful in patients with subtle thoracic limb deficits. The patient should be supported under the abdomen, so the pelvic limbs are held off the ground, and then should be walked forward on its thoracic limbs. With this posture, vision is compromised and the animal relies heavily on general proprioception. With the head extended in normal position, the patient should walk with symmetric movements of both thoracic limbs. Scuffing, knuckling, or a delay in onset of the swing phase of the gait is considered abnormal. With severe lesions, patients may carry their head flexed with the nose oriented close to the ground for support. The most reliable tendon reflex is the patellar reflex, which is mediated by the femoral nerve through spinal cord segments L4-L6. Testing is performed with the patient in lateral recumbency, and the limb not directly on the ground (“up limb”) is evaluated. With the limb relaxed and held in partial flexion, the clinician should elicit this reflex by lightly tapping the patellar ligament with a plexor or pediatric hammer. This reflex should be tested with the patient on both sides. In some patients, this reflex is elicited more easily in the limb adjacent to the floor. It is noteworthy that one or both patellar reflexes may be absent in older dogs with no other neurologic signs.5 The response typically is graded as absent (0), hyporeflexive (+1), normal (+2), hyperreflexive (+3), or clonic (+4). An absent or hyporeflexive reflex occurs with disease of a portion of the reflex arc (most commonly in the lower motor neuron unit). Hyperreflexia or clonus may be present in upper motor neuron diseases. Ultimately, the finding of an absent or hyporeflexive reflex is consistent with a disease affecting the afferent limb, the efferent limb, or spinal cord segments involved in the reflex arc; a normal to hyperreflexive reflex is consistent with a lesion cranial to the spinal cord segment containing the reflex arc.

Neurologic Examination and Neuroanatomic Diagnosis

The Neurologic Examination

Posture and Gait

Paresis

Postural Reactions

Postural Reaction Tests

Proprioceptive Placing (Paw Replacement) and Tactile Placing Responses

Spinal Reflexes, Muscle Mass, and Muscle Tone

Patellar Reflex

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neurologic Examination and Neuroanatomic Diagnosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue