Chapter 12 Neurologic Diseases

BOVINE NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

Cranial Nerves

BRAIN

Malformation of the Brain

Cerebellar Hypoplasia/Atrophy

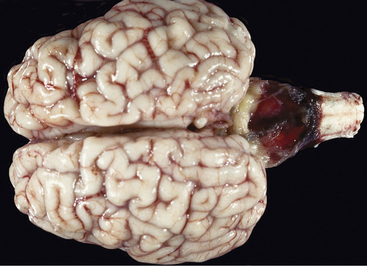

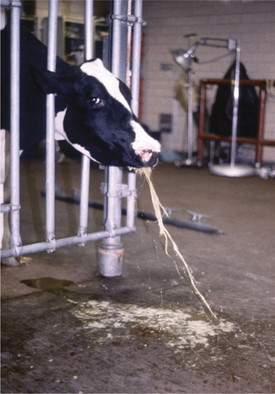

This is the most common brain malformation observed in the northeastern United States and is the result of an in utero infection with the bovine virus diarrhea virus (BVDV) agent, usually between 100 and 200 days of gestation. The inflammation peaks about 14 days after infection and resolves before birth. The small malformed cerebellum seen at birth reflects atrophy of the already differentiated cerebellar parenchyma at the time of the infection and hypoplasia from the destruction of the embryonic precursor cells primarily in the external germinal layer (Figure 12-1). In most affected calves, the cerebellum is largely absent with only a few remnants of cerebellar folia remaining (see video clips 25 to 27). Clinical signs vary. Some calves are unable to stand and often thrash around in their attempts to get up, and they exhibit periods of opisthotonos and sometimes abnormal nystagmus. Others can stand and walk but have a base wide posture, stagger, and weave from side to side with a hypermetric gait and balance loss (Figure 12-2).

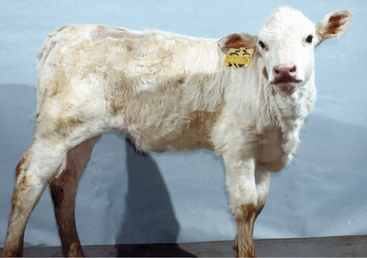

Figure 12-2 A 3-week-old calf with severe cerebellar hypoplasia and atrophy (see Figure 12-1) that was able to stand; notice the base-wide stance and lowered head position.

It is important to obtain a necropsy diagnosis for these calves because their clinical signs do not differ from a possible genetically induced cerebellar malformation. The latter has been observed in Angus and Scottish Highland calves with a symmetrically reduced cerebellar size but no gross or microscopic evidence of any destructive process. In addition, there is no trapezoid body on the ventral surface of the rostral medulla, but there is an abnormal band of parenchyma passing across the fourth ventricle just caudal to the cerebellar peduncles with a nucleus at each end. This may be the trapezoid body and the cochlear nuclei in an abnormal position that cannot be explained by an in utero viral infection. The fourth ventricle is remarkably reduced in size.

Meningoencephalocele

This malformation occurs along the midline of the calvaria through an opening referred to as cranioschisis or cranium bifidum. The size of the extracranial accumulation of CSF may be extensive, producing a soft fluctuant pendular skin-covered structure (Figure 12-3). Although it is possible that some of these malformations may just be meningoceles, microscopic study of the tissues containing the CSF usually reveals a thin layer of brain parenchyma associated with the meninges beneath the skin, and therefore these are meningoencephaloceles.

Prosencephalic Hypoplasia-Telencephalic Aplasia

Calves with this sporadic unique malformation are alive at birth and unable to stand. Their cranium is flattened between two normal orbits with normal eyeballs. A dorsal midline skin defect is present at the level of the caudal aspect of the orbits. There usually is a slight bloody discharge from this opening, which probably contains CSF. The skin tissue surrounding the opening is continuous caudally with a malformed diencephalon at the rostral portion of the brainstem. There are no cerebral hemispheres, just a malformed brainstem and cerebellum. There are no recognizable geniculate nuclei, no mesencephalic colliculi, and the cerebellum is elongated. With the exception of the olfactory nerves, all the remaining CNs are present, including the optic nerves that extend to the two eyes. In humans, this defect is called anencephaly, which is inappropriate because there is a brainstem and cerebellum present. There is no adequate term for this combination of malformations, and we have chosen to call this prosencephalic hypoplasia with telencephalic aplasia. The cause is unknown in cattle but has been blamed on folic acid deficiency or hyperthermia in humans.

INFLAMMATION OF THE BRAIN

Meningitis

Signs

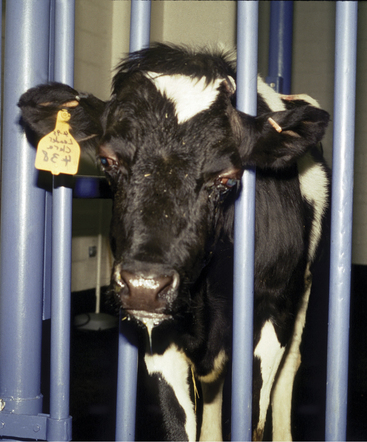

Signs of meningitis in neonatal calves may be overt, with classical fever, somnolence, intermittent seizures, head pressing, and blindness, or be masked by hypovolemic shock and collapse in overwhelming septicemias. When meningitis precedes other major organ infection, signs of fever, depression, head pressing or “headache” appearance, seizures, and cerebral blindness signal the diagnosis (Figure 12-4). The gait is stiff, and the head is often held straight, with the muzzle extended. The condition is painful, and the animal may appear to have a “headache” with the eyelids partially closed and the head and neck extended. However, when meningitis coexists with other organ infection such as uveitis, septic arthritis, and omphalophlebitis, it may be difficult to recognize specific signs of meningitis. Overwhelming septicemia results in rapid deterioration of the neonate such that shock may mask clinical signs of meningitis (see video clip 31). Some calves affected with meningitis have opisthotonos—perhaps caused by cerebral inflammation and edema exerting pressure on the cerebellum and caudal brainstem (Figure 12-5). Affected calves are generally between 2 and 14 days of age with the mean being 6 days of age.

Adult cattle affected with meningitis usually have fever and profound depression. A stiff, stilted gait and “headache” appearance (stargazing or continually pressing head or muzzle against an object) are common (Figure 12-6), but seizures are less common than in calves. Inflammation of the visual cortex can result in blindness with normal pupillary function.

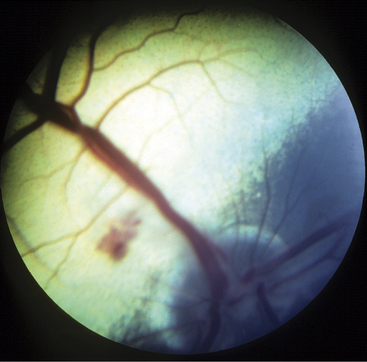

Meningitis caused by H. somni is acute, with affected cows becoming extremely depressed within a few hours. Fever usually is present and may be as high as 106.0° F/41.11° C. The depression progresses over 12 to 24 hours to total inappetence and somnolence, and the affected cow may be unable to rise (Figure 12-7). Depression is so severe that presence or absence of vision may be difficult to determine, and occasional seizures are observed in some patients. Affected cows die within 24 to 48 hours of onset unless treated specifically for H. somni. Herds experiencing H. somni meningitis often have multiple cases over a period of several months, until appropriate diagnostics and preventive measures are used. TME caused by H. somni, although rare, does occur in growing dairy heifers and causes acute severe neurologic disease that may be accompanied by retinal lesions (Figure 12-8).

Brain Abscesses and Pituitary Abscesses

Etiology

Brain abscesses, similar to abscesses affecting the spinal cord, usually arise from embolic spread of bacteria from distant sites of infection or during septicemic episodes. Calves develop brain abscesses most commonly from umbilical sepsis and extensions from otitis media/interna, whereas those in adult cattle have been associated with chronic infections, such as abscesses resulting from hardware disease, chronic musculoskeletal abscesses, or rumenitis. In addition, direct extension from chronic frontal sinusitis and bacterial seeding associated with nose rings in bulls are other potential causes of brain abscesses in adult cattle. Although the relationship with frontal sinusitis is obvious, the inferred higher risk of cattle or bulls with nose rings for brain or pituitary abscesses is very interesting. Theories to explain this phenomenon center around the complex rete mirabile circulation that encircles the pituitary region and is suspended in the cavernous sinuses, which drain the nasal cavity. Arcanobacterium pyogenes is the most common organism isolated from brain abscesses in cattle.

Signs

Signs vary tremendously, depending on neuroanatomic location of the brain abscess. Initial signs such as mild depression, dysphagia, hemiparesis, and hemianopsia may be subtle and will frequently go undetected by the owner. As the abscess enlarges, varying degrees of visual disturbance, paresis, ataxia, profound depression, and CN signs become apparent. Head pressing may be observed (see video clips 32 and 33). Calves tend to be affected between 2 and 8 months of age, thereby being past the typical age for neonatal meningitis. If the abscess becomes sufficiently large, it will interfere with venous return of blood from the orbital region and cause exophthalmos (Figure 12-9). Adult cattle can be of any age. Depression and a stargazing attitude have been observed in cattle with cerebral abscesses. Bradycardia coupled with depression and a stargazing attitude has been described to indicate a pituitary abscess (Fox FH, personal communication, 1985, Ithaca, NY), but other signs such as blindness, dysphagia, or CN signs are possible. A review of pituitary abscesses found that approximately 50% had bradycardia in addition to other neurologic signs. The bradycardia may result from involvement of hypothalamus or may be caused by the anorexia.

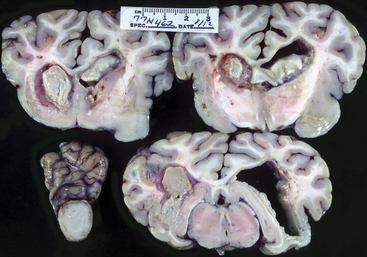

Abscesses localized to one cerebral hemisphere usually cause blindness with intact pupillary function in the contralateral eye (hemianopsia) as a result of optic radiation or cerebral cortical injury (Figures 12-10 and 12-11). Similarly, contralateral abnormal postural reactions would be anticipated with a normal gait in animals light enough to be hopped or a scuffing of the limbs when walked in a tight circle or over rough ground. Propulsive tendencies may appear also with large cerebral abscesses. Anorexia secondary to severe depression may be accentuated by specific CN dysfunction if the abscess directly or indirectly damages the brainstem. Some affected cattle continue to eat despite extensive space-occupying abscesses.

Figure 12-11 Sections of brain from calf shown in Figure 12-10. The left side of the photo illustrates the left side of the brain.

Diagnosis

Antemortem confirmation of brain or pituitary abscesses may be difficult. The neurologic signs are the most helpful to diagnosis—especially in young animals in which inflammatory lesions are more common than other intracranial disorders. Serum globulin should be assessed because it frequently is elevated in adult cattle with brain abscesses but may be variable in calves and young cattle. A neutrophilic leukocytosis may be anticipated, but in fact the hemogram often is normal.

Listeriosis

Etiology

Once established in the brainstem, the organism proliferates in the pons and medulla regions and may spread elsewhere. The trigeminal nerve and its neighboring CN nuclei are subject to injury as a result of neuritis, encephalitis, and meningitis. The classical histologic lesions of listeriosis consist of microabscesses subsequent to focal necrosis with abundant neutrophils and perivascular cuffing with mononuclear cells.

Signs

Depression coupled with a variable array of CN signs compose the major clinical signs of listeriosis in cattle. Classically the disease was known as circling disease because of the frequency of this clinical sign. The anatomic basis for this is unclear. Asymmetric involvement of vestibular nuclei with loss of balance and circling to that side is one explanation. However, the propulsive tendency to circle suggests involvement of extrapyramidal system nuclei such as the substantia nigra or the descending reticular formation. Although propulsion is a common prosencephalic sign, this portion of the brain is much less affected in listeriosis. Patients may circle until they collapse from exhaustion or eventually wander into solid objects. Stanchioned cattle constantly push or propel themselves into the stanchion in an effort to circle (Figure 12-12).

Anorexia, or perhaps an inability to eat, is present in most cattle affected with listeriosis and may be caused by specific CN deficits in CN-V, -VII, -IX, -X, and -XII, as well as depression. Inability to drink frequently accompanies the inability to eat but is not present in all cases. Individual or combinations of CN injuries unique to each patient may occur (Figure 12-13) (see video clips 34 and 35).

Lesions of CN-V motor nucleus or mandibular nerve create weakness in the muscles of mastication. When severe and bilateral, a dropped jaw results (Figure 12-14). When mild, weakness may be appreciated during manual efforts to open the patient’s mouth. Although this lesion may be unilateral, it is only obvious clinically when bilateral. Difficulty in prehension and mastication of food results.

Facial nerve deficits caused by lesions involving the facial nucleus or the intramedullary components of the facial nerve are a very common sign of listeriosis and often are unilateral, causing a drooped ear, ptosis, and flaccid lip (Figure 12-15). Very early cases or cases recovering from complete facial nerve paralysis occasionally have facial nerve irritability evidenced by eyelid or lip spasticity in response to noxious stimuli. Although unilateral deficits in CN-VII are classic for Listeria meningoencephalitis of cattle, the deficits may be subtle, incomplete, or bilateral and therefore require careful evaluation during the neurologic examination. Exposure keratitis is the major ophthalmic complication found in listeriosis patients and results from facial nerve dysfunction and subsequent failure of tear distribution to prevent corneal desiccation or injury. Additionally, involvement of the parasympathetic facial nucleus may cause a decrease in the aqueous phase of the tear secretion. Exposure keratitis can rapidly progress with resultant deep corneal ulceration, uveitis, corneal perforation, and endophthalmitis unless addressed promptly. Endogenous uveitis with hypopyon or endophthalmitis has been suggested as possible ophthalmic complications by some authors, but in our experience, exposure keratitis and exogenous infection of the eye are the most common ophthalmic complications of listeriosis in cattle (Figure 12-16).

Figure 12-15 Listeriosis. Classical appearance of unilateral CN-VII paralysis with ear droop, ptosis, and flaccid lip.

Damage to vestibular nuclei affects central vestibular control, leading to head tilt, circling, and vestibular ataxia. Abnormal posture and truncal ataxia also are possible; when these signs are present, the cow’s trunk leans toward the affected side and is flexed so a concavity toward the affected side is present. When abnormal nystagmus is observed, the direction (fast phase) is variable, as expected with a central vestibular deficit. Adjacent unilateral lesions affecting reticulospinal UMN and spinocerebellar GP pathways may cause ipsilateral paresis and ataxia. Bilateral lesions in this area resulting in spastic tetraparesis and GP ataxia may be severe enough to cause recumbency.

Lesions involving neuronal cell bodies of CN-IX and -X in the nucleus ambiguus cause dysphagia and salivation. Vomiting and/or bloat occasionally are observed (Figure 12-17) as an early sign of listeriosis in cattle and are thought to result from inflammatory irritation of the parasympathetic vagal neurons in the medulla.

Diagnosis

TME or pure meningitis caused by H. somni can lead to acute signs of brain disease in young cattle. Although TME occurs mainly in beef cattle, we occasionally observe this problem in dairy heifers. Signs vary based on the multifocal nature of the septic thrombi within the brain, and CN signs are possible, as well as the typical cerebral signs and depression. Fever may be present in the acute phase, and blindness caused by chorioretinal hemorrhages and thrombosis is possible. The CSF, however, helps differentiate H. somni from listeriosis because, although protein values are elevated in both diseases, the nucleated cell count with H. somni usually is greatly elevated and consists primarily of neutrophils. The fluid may be grossly discolored on visual inspection.

Treatment

Nursing care, including a well-bedded box stall with good footing, is essential to survival of cattle affected with listeriosis. Assuming intensive antibiotic therapy, fluid therapy, and supportive care are given, prognosis is fair to good for cattle infected with listeriosis that are ambulatory when the diagnosis is made. The prognosis for cattle that are recumbent and unable to rise at the time of diagnosis is very poor.

Rabies

Clinical Signs

The clinical signs at the onset relate to the area of the body that is bitten and where the virus first enters the nervous system. Spinal cord signs are seen frequently. These may include subtle hind limb lameness or shifting of weight in the hind limbs that progresses to knuckling of one or both fetlocks (see video clip 36). Ataxia and weakness may follow these signs and progress until the cow needs help getting up or becomes completely paralyzed in the pelvic limbs (Figure 12-18). In some cases, there is a spastic uncontrolled flexion of the limbs. Associated with these lumbar and sacral signs, constipation, tenesmus, paraphimosis (males), dribbling of urine from bladder paralysis, and a flaccid tail and anus may become apparent. Therefore progressive signs of spinal cord or spinal nerve dysfunction should raise concern for rabies. With head bites, CN signs may occur initially.

Dysphagia, salivation, and a weak tongue are apparent in some cattle affected with rabies. An inability to drink usually accompanies these signs, which are reflective of pharyngeal paralysis. Bellowing is described as “peculiarly low pitched and hoarse and may progress to bubbly sounds prior to death.” Laryngeal paralysis associated with pharyngeal dysfunction may contribute to these sounds.

Pseudorabies (Aujeszky’s Disease, Mad Itch)

Etiology

This herpesvirus of swine is the cause of pseudorabies. Often a mild disease in swine, this disease is highly fatal in cattle and may cause signs similar to rabies—hence the name, pseudorabies. This is a rare disease in dairy cattle because pigs and dairy cows seldom are housed together. However, trends in agriculture change constantly, and diversification that includes swine and dairy cattle operations located on the same premises could occur, thereby risking spread of this virus from swine to cattle.

Bovine Herpesvirus Encephalitis

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Clinical signs of respiratory disease may be concurrent with neurologic signs, especially with BHV1. Prosencephalic signs predominate and are usually accompanied by a fever. Most affected animals remain visual, which helps separate many of the infectious encephalitides from metabolic or toxic diseases affecting the cerebral cortex. I (TJD) have analyzed CSF on only one BHV encephalitic calf (Figure 12-19), and it had a lymphocytic pleocytosis. If BHV-infected cattle survive, they will seroconvert in 7 to 10 days. Animals that die with nonsuppurative encephalitis can be confirmed as having BHV by immunohistochemistry. Genomic analysis or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to differentiate between the two strains. The CNS lesion consists of a diffuse nonsuppurative meningoencephalomyelitis affecting both the gray and white matter.

Thrombotic Meningoencephalitis

TME is caused by Histophilus somni, formerly known as Haemophilus somnus. This small coccobacillus attacks vascular endothelium, causing a septic vasculitis with thrombosis. The parenchymal lesions of ischemic and hemorrhagic infarction are secondary to the primary vascular lesions that can occur anywhere in the CNS. In addition, similar vascular lesions can occur in the lung, heart, skeletal muscle, and joints. Death may occur acutely without evidence of neurologic signs. Pyrexia is present in clinically ill patients. This disease is more common in feedlot cattle than in pastured or dairy animals. In New York State pulmonary signs and lesions are the most common manifestation of this disease. Diagnosis and treatments for TME are discussed on p. 510.

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy

Etiology

In addition to horizontal transmission, presumably from feeding contaminated ruminant tissue, there is vertical transmission of the TSE agent as well. BSE-infected cattle were three times more likely to have infected offspring than noninfected cows during the England outbreak. After banning the feeding of ruminant meat and bone meal to cattle in the United Kingdom, there has been a dramatic decrease in the incidence of BSE. In contrast, incidences in some other European and non-European countries have increased during the same period.

DEGENERATIONS: METABOLIC AND TOXIC BRAIN DISEASES

Polioencephalomalacia

Clinical Signs

Cerebrocortical signs predominate in PEM. Depression and anorexia are present in both calves and adults, but these signs may only be present for a short time before more overt signs of cortical disease become apparent. Blindness with intact pupillary function is one of the first signs observed because of the sensitivity of the visual cortex to the ongoing pathology (see video clips 37 and 38). Pupillary response to light may be lost in some recumbent cases as the disease progresses and presumably the oculomotor nerve is compressed. Head pressing and odontoprisis may be observed or an extended head and neck typical of cattle with “headache”-type pain. A slow shuffling gait is usually apparent if the animal is able to walk. Vocalization, as observed in some early cases in goats, is usually not observed in calves or adult cattle with PEM. A dorsomedial strabismus thought to be caused by involvement of the CN-IV nucleus is common in calves and yearlings but observed less often in adult cattle. Muscle tremors and salivation also may occur.

If the disease has progressed enough to cause recumbency, opisthotonos frequently is observed, and abnormal nystagmus, seizures, or coma is likely to follow (Figure 12-20). Untreated cases may die within 24 to 96 hours, depending on the severity of the metabolic dysfunction. CN signs other than possible dorsomedial strabismus usually are not present (Figure 12-21). Although optic disc edema has been reported to occur, we have never observed this in any calf or cow affected with PEM. Therefore in our opinion, blindness is entirely of cortical origin (Figure 12-22). Associated with either cortical blindness or cerebral edema, cattle may have a stargazing appearance (Figure 12-23).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree