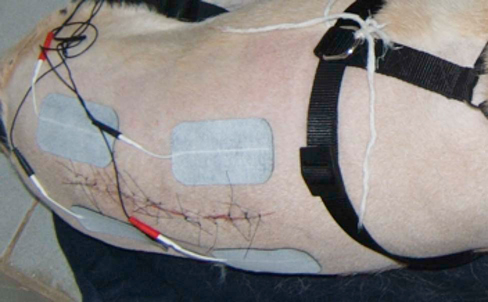

Neurologic conditions are often very painful. Adequate analgesia is important to achieve a successful outcome. Pain-free animals are relaxed and cooperative, recover faster and more completely, and owners are much happier and more compliant with recommendations when their pet is comfortable. Pain originates from multiple sources. Nociceptors respond to a variety of stimuli, including mechanical (e.g., pinching a toe), thermal (heat, cold), and chemical. Activation of superficial mechanical or thermal nociceptors initiates sharp, pricking pain that is precisely localized and ceases when the stimulus is no longer present. Increased intensity of stimulus activates slower conducting pain felt as burning or throbbing that is poorly localized. With tissue injury and inflammation, this type of pain persists even after the initial injury. Patients with neurologic disease can develop neuropathic pain, including spontaneous pain, paresthesia (tingling, prickling), and dysesthesia (paroxysmal shooting, shocklike pain or continuous burning pain). One of the most common causes of neuropathic pain is intervertebral disk herniation that compresses or stretches a nerve root.1 Analgesic and antiinflammatory drugs are important in managing pain in neurologic patients. Rehabilitation modalities are used to supplement medications and reduce drug requirement. Cryotherapy (see Chapter 18) reduces pain through the gate control theory described by Melzack and Wall that is governed by balance between excitation and inhibition in the dorsal horn, slowed nerve conduction velocity and increased threshold to nerve stimulation. Duration of analgesia lasts at least 30 minutes posttreatment providing an opportunity to perform passive manipulation. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (see Chapter 20) also works under the same gate control theory (Figure 34-1). Laser therapy (see Chapter 21), and massage (see Chapter 27) may also reduce pain and enhance relaxation. A good time to correct the stance is meal times. Although the patient is occupied with eating, gently correct the stance to a normal position (Figure 34-2). Repeat this as needed to maintain a proper stance. Neurologic patients are at risk of several complications including shortening of ligaments and tendons, muscle atrophy and contracture, pressure sores, urinary tract infections, and respiratory tract infections that can develop secondary to immobility, recumbency, and altered biomechanical stresses. Modalities such as passive range of motion (PROM) and stretching exercises decrease the risk of contractures. Dry, well-padded bedding and frequently repositioning recumbent patients help prevent pressure sores (Figure 34-3). Bony prominences such as the ischiatic tuberosity, greater trochanter, and xiphoid are inspected frequently to detect early skin lesions. Urine retention is prevented by urethral catheterization or manual bladder expression (see Chapter 16). Helping the patient maintain a normal, upright posture as much as practical minimizes many of the adverse effects of recumbency. Patients with loss of sensation or abnormal sensation are at risk of damaging their limbs from dragging or self-mutilation (Figure 34-4). In these patients, the affected limb(s) should always be protected to prevent trauma. Specific neurologic diseases and their management are discussed in the following sections. Intervertebral disk (IVD) disease is a syndrome of pain or neurologic deficits, resulting from displacement of part of the disk. Disks are interposed between each vertebral body except the first and second cervical vertebrae and each of the fused sacral vertebrae. The IVD is situated between adjacent vertebral end plates and is composed of an outer fibrous ring, the annulus fibrosus, which surrounds an eccentric amorphous gelatinous center, the nucleus pulposus.2 Fibrous metaplasia is an age-related degenerative process that occurs in any breed but is more common in nonchondrodystrophic dogs 7 years of age and older. It is characterized by a fibrous collagenization of the nucleus pulposus and degeneration of the annulus fibrosus. Fibrous metaplasia predisposes to disk protrusion, in which disk material is displaced from the disk space but is contained within an intact annulus (also called Hansen Type II). Nonchondrodystrophic breed dogs can also suffer extrusions and less commonly chondrodystrophic breeds suffer protrusions.2,3 The lifetime prevalence for intervertebral disk disease is approximately 3.5% and overall mortality rate attributed to disk disease is about 1%. Miniature dachshunds have the highest risk, with a lifetime prevalence of 20% and other chondrodystrophic breeds are also at increased risk.4 Cervical disk disease commonly affects small, middle-age to older chondrodystrophic breeds, with beagles and dachshunds having the highest risk.4,5 The C2-C3 disk space is most commonly affected, with the frequency decreasing at progressively more caudal disk spaces. Cervical disk disease in large-breed dogs is usually associated with cervical spondylomyelopathy and is discussed separately. Neck pain is the most common and often the only sign of cervical disk disease and is present in approximately 90% of affected dogs.5 This is manifested as low head carriage, stiffness or decreased motion of the neck, vocalizing, and spasms of the neck muscles. Some dogs exhibit lameness of one or both thoracic limbs, owing to nerve root or spinal nerve attenuation (root signature). In severe cases, there is ataxia, conscious proprioceptive deficits, weakness, or paralysis of all limbs. Spinal reflexes are usually normal to exaggerated, although reflexes may be weak or absent in the thoracic limbs with caudal cervical disk extrusions and occasionally with more cranial lesions.6 Other causes of cervical lesions include trauma, neoplasia, meningitis, discospondylitis, cervical spondylomyelopathy, and atlantoaxial instability. Treatment options include surgery and nonsurgical therapy, with the decision based on the duration and severity of clinical signs. Nonsurgical therapy is indicated as the initial treatment in patients with no or mild neurologic deficits. The most important aspect of treatment is strict cage confinement to minimize stress on the damaged disk to allow the disk time to heal. A harness is used instead of a neck collar and leash. A short course of antiinflammatory doses of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is administered if necessary for pain control. Muscle relaxants may be beneficial in some patients with spasm of the cervical muscles. Analgesic drugs without cage confinement are contraindicated because they may lead to increased patient activity and risk further disk extrusion. If the patient does well, cage confinement is continued for at least 2 to 3 weeks. About 50% of dogs with neck pain caused by disk disease recover with nonsurgical therapy. Recurrence of signs occurs in about one third of patients.7 Surgery is indicated for patients with substantial neurologic deficits, neck pain unresponsive to appropriate nonsurgical therapy, or recurrent bouts of neck pain. Removal of extruded disk material by a ventral slot to decompress the spinal cord and nerve roots is the procedure of choice in most patients. Dorsal hemilaminectomy may be necessary for lateral or far-lateral extrusions. In chondrodystrophic dogs, prophylactic fenestration of the other disk spaces at the time of ventral slot is indicated to decrease the risk of extrusion of another disk. Fenestration alone of the affected disk is not indicated because it does not allow removal of extruded disk material.8 In dogs with neck pain and mild neurologic deficits, the success rate with surgery is about 95%. Nonambulatory dogs have a good outcome in 62% to 100% cases, with small dogs (≤15 kg) having a better prognosis than larger dogs.5,8,9 Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management included drugs described for medical management. Postoperative physical rehabilitation is an integral part of the overall care of the patient. Physical rehabilitation as part of medical management includes massage, heat therapy, electrical stimulation (ES), therapeutic ultrasound (US), therapeutic laser for muscle spasms and pain relief. Whirlpool therapy may also be cautiously used in patients carefully supported in a sling as long as there is no struggling (Figure 34-5). For strengthening, underwater treadmill walking or swimming may be initiated after the incision site is healed. The time of suture removal is generally a safe time to start hydrotherapy. Some therapists start some form of aquatic therapy earlier, with caution to avoid submersion of the incision, especially an incision in the ventral cervical region. In any case, the incision should be sealed, with apposed edges, no discharge or drainage, and no separation of the incision with gentle manipulation of the edges. In small dogs, a whirlpool may be used for aquatic therapy. The duration of aquatic therapy depends on the fitness, endurance, and ability of the patient. Assistance or life preservers are provided as required (Figure 34-6). If the patient does not actively move its limbs through an adequate range of motion, assistance is given either by passively moving the limb(s) or by providing resistance to motion to stimulate the patient to engage the limb against the applied resistance. Patients can be placed on exercise rolls to strengthen proprioception and joint stability. They may be further challenged with mild bouncing and slight movements of the ball to create an unstable surface (Figure 34-7). Requiring patients to walk on foam, bubble wrap, or an inflatable object or challenging them with a rocker board (Figure 34-8) will also help them to develop stability and proprioception. To assist in regaining kinesthetic awareness, patients can be challenged to step over objects of varying shapes and sizes (Figure 34-9). Small objects are initially used; the height and width are increased as the patient progresses. Strengthening the thoracic limbs can be achieved by ambulating on land, a dry treadmill (Figure 34-10), and deep water and underwater treadmill hydrotherapy. Additional strengthening exercises include walking down inclines with variable pitch, wheel barrowing (Figure 34-11), and increased weight bearing with an exercise roll beneath the pelvic limbs (Figure 34-12). Analogous exercises may be used to strengthen the rear limb muscles, such as walking up inclines, dancing, and weight bearing with the forelimbs on an exercise roll. Thoracolumbar herniations are most common from T12-T13 to L1-L2, although other areas may also be affected. dachshunds, cocker spaniels, and beagles and other chondrodystrophic breeds are at increased risk.4 Type I extrusions are most common in these breeds. Type II protrusions are more common in large, nonchondrodystrophic dogs, but large dogs can also suffer acute, Type I extrusions.10 About 85% of dogs with back pain and no neurologic deficits will improve with nonsurgical therapy, as described for cervical disk disease. Surgery is indicated in patients with substantial neurologic deficits, or back pain refractory to nonsurgical therapy. Patients with a sudden onset of severe neurologic deficits need urgent surgery. Removal of extruded disk material via hemilaminectomy is the procedure of choice in most cases. Fenestration of the affected intervertebral disk space is routinely performed. Prophylactic fenestration of other thoracolumbar disk spaces reduces recurrence in chondrodystrophic breeds.11 The prognosis depends in large part on the severity and duration of the neurologic deficits. The recovery rate for nonambulatory dogs with acute extrusions and intact deep pain perception is 85% to 95%, with most patients regaining ambulation in 1 to 4 weeks. For dogs with loss of deep pain perception, the recovery rate is about 50% if surgery is performed within 24 hours of the loss of deep pain. This decreases further if surgery is delayed for longer than 24 hours. The recovery rate for large breed dogs with chronic protrusions is much lower, ranging from 22% to 52%.4 Ambulation is allowed at controlled paces in patients with motor control. Assisted tail or sling walking and underwater treadmill hydrotherapy may be used to unload weight before attaining complete ambulatory independence. Strengthening exercises are initiated as independent ambulation improves (Figures 34-13 through 34-17). Activities include ascending and descending inclines, walking in circles or figure eights, walking on terrain with varying textures (carpet, grass, sand), stepping over objects of varying size to regain proprioceptive awareness, and practicing sit-to-stand activities for coordination. Nonslip flooring is ideal to encourage proprioception and appropriate limb placement. Commercially available booties may provide protection for dogs that tend to knuckle over on the dorsum of the paw or drag the paws while ambulating.

Neurologic Conditions and Physical Rehabilitation of the Neurologic Patient

General Considerations

Figure 34-2 While the patient is eating, the stance may be corrected and gentle weight shifting exercises may be performed.

Figure 34-3 Dry, well-padded bedding and frequent repositioning of recumbent patients help prevent pressure sores.

Figure 34-4 Patients with loss of sensation or abnormal sensation are at risk of damaging their limbs from dragging or self-mutilation. The affected limb(s) should always be protected to prevent trauma.

Intervertebral Disk Disease

Cervical Disk Disease

Physical Rehabilitation for Cervical Disk Disease

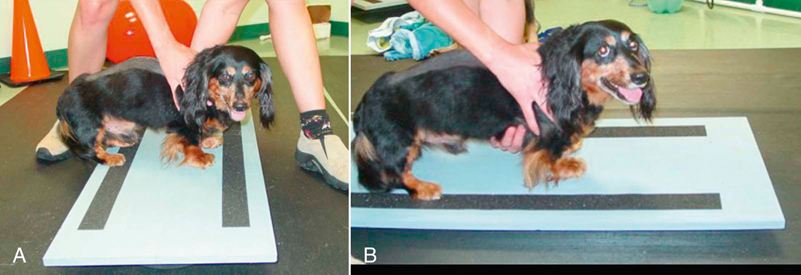

Figure 34-8 Rocker boards for rehabilitation. A, Side-to-side motion. B, Forward and backward motion.

Thoracolumbar Disk Disease

Physical Rehabilitation for Thoracolumbar Disk Disease

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neurologic Conditions and Physical Rehabilitation of the Neurologic Patient

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue