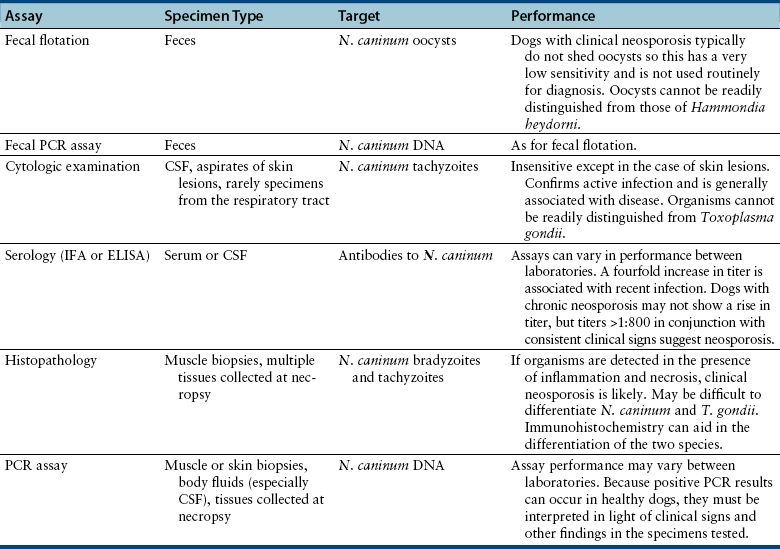

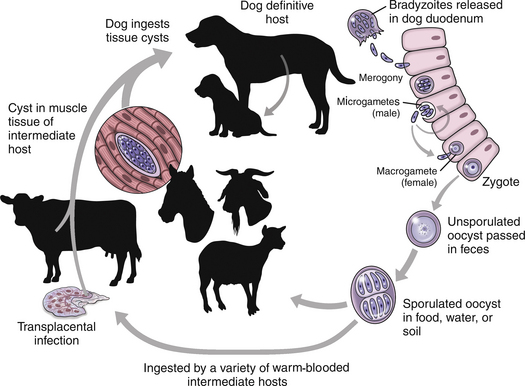

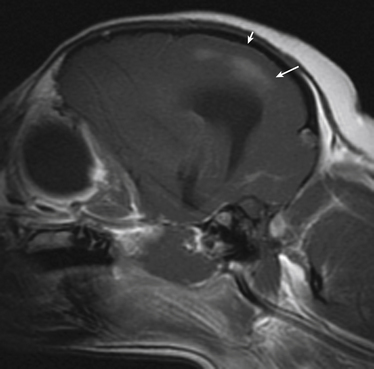

Chapter 73 Neospora caninum is an obligately intracellular protozoan pathogen that closely resembles Toxoplasma gondii; before its description in 1984, it was misidentified as T. gondii. In contrast to T. gondii, domestic dogs and wild canids (coyotes, dingos, and probably wolves), and not cats, act as definitive hosts of N. caninum and shed oocysts after ingestion of N. caninum tissue cysts (enteroepithelial cycle) (Figure 73-1). Clinical neosporosis results from systemic replication of N. caninum tachyzoites (which divide by a process known as endodyogeny) and has been described in dogs and certain domestic and wild herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats, deer, and marsupials. A related parasite, Neospora hughesi, sporadically causes myeloencephalitis in horses.2 This organism has an unknown definitive host that is unlikely to be the dog, based on experimental infection studies.3 FIGURE 73-1 Life cycle of Neospora caninum. Dogs become infected when they ingest tissue cysts in bovine placental material and other bovine tissues. Bradyzoites are released in the intestine and transform into merozoites, where they undergo merogony. A zygote forms and is shed in the feces as an unsporulated oocyst. In addition, organisms can penetrate the dog’s intestinal tract and form tissue cysts. Reactivation of these cysts in pregnancy can result in repeated transplacental transmission to the fetus. Herbivores are infected when they ingest sporulated oocysts. Infection of cattle can lead to transplacental spread of tachyzoites and abortion. N. caninum is one of the most important causes of infertility, abortion, and neonatal mortality in cattle worldwide. Sheep can also develop reproductive and neonatal disease, but the economic importance of N. caninum in sheep is less clear when compared with cattle.4 Herbivores likely become infected when they ingest oocysts shed in canine feces or through subclinical transplacental transmission. Oocysts sporulate and become infective 24 to 72 hours after they are shed in canine feces and can survive in the environment for prolonged periods. After oocysts are ingested, sporozoites are released in the intestinal tract and penetrate intestinal epithelial cells. Organisms can then disseminate to a variety of tissues, where they ultimately encyst as bradyzoite cysts. In dogs, pregnancy is associated with reactivation of bradyzoite cysts, with replication of tachyzoites and subsequent abortion or transplacental transmission. In breeding dogs, repeated reactivation of N. caninum replication occurs in late gestation with successive pregnancies, so that multiple litters of puppies can be affected. Transmission may also occur via the transmammary route. Infection of immunologically naïve cattle late in pregnancy is most likely to lead to transplacental spread with abortion (also known as exogenous transplacental transmission).5 However, transplacental transmission as a result of reactivation of latent infection during pregnancy (endogenous transplacental transmission) can also occur.6 The pregnant cow typically shows no other overt clinical signs of infection. Although antibodies to N. caninum have been found in cats and humans, naturally occurring neosporosis has not been described in these species. Aside from transplacental transmission, dogs can become infected and shed oocysts when they ingest bovine placental material as well as other bovine tissues, such as muscle, liver, brain, and heart muscle.7 This horizontal transmission is important and is thought to maintain infection in the dog population.8 The DNA of N. caninum has been found in birds, small rodents, and lagomorphs, but whether predation of these species leads to oocyst shedding by dogs is not clear.4 Experimental evidence suggests that ingestion of infected chicken eggs by dogs may lead to oocyst shedding.9 However, ingestion of oocysts by dogs does not lead to oocyst shedding or development of tissue cysts.10 When dogs do shed oocysts, the shedding begins 5 to 13 days after infection, and only low numbers of oocysts are shed for a short period (several days); seroconversion does not always occur. Rarely, protracted oocyst shedding (several months) by dogs has been described.11 Puppies shed more oocysts than adult dogs,12 and the number of oocysts shed decreases with repeated exposures to bradyzoite cysts. In dogs, seroprevalence increases with age (because of an increased likelihood of exposure through horizontal transmission over time) and is higher in free-roaming dogs than in pet dogs. Dogs that reside on cattle farms or dogs in rural areas are also more likely to be seropositive than dogs that reside in urban areas.13–16 Introduction of infected dogs to a farm can lead to outbreaks of abortion in cattle on the farm,17 and the more dogs present on a farm, the greater the chance that cattle will be exposed. Although mixed breed dogs are more likely to be seropositive (exposed) than purebred dogs, purebred dogs often develop clinical neosporosis,18 possibly because of genetic defects in cell-mediated immune function. Commonly affected breeds in the literature and/or in the author’s practice include boxers, Rhodesian ridgebacks, bull mastiffs, greyhounds, basset hounds, Labrador retrievers, Rottweilers, and West Highland white terriers. Although exposure to N. caninum is common, clinical disease is uncommon in dogs. The development of clinical neosporosis, the signs that develop, and their rate of progression may depend on the virulence of the infecting N. caninum strain and the age and immunocompetence of the host.4,19 Many affected dogs are infected transplacentally, after which clinical signs usually become apparent from 4 weeks to 6 months of age. Up to 50% of puppies in a litter can be infected, but not all puppies develop signs simultaneously, and sometimes only one puppy in the litter develops clinical illness.20 Stillbirths and neonatal deaths may also be reported.18 Reactivation of subclinical infection can occur in older dogs after treatment with immunosuppressive drugs or chemotherapy.21–23 Horizontal acquisition of infection by adult dogs may occur through consumption of raw meat; one dog that developed neosporosis had a history of being fed raw elk meat.22 Transplacental infection of puppies usually leads to myositis and polyradiculoneuritis that initially involves the lumbosacral spinal nerve roots. This is manifested as ascending paralysis, muscle atrophy, and fibrous muscle contracture with arthrogryposis (joint contracture), hyperextension of the pelvic limbs, and loss of patellar reflexes.18 Early signs of disease include exercise intolerance, ataxia, a high-stepping gait, splaying of the pelvic limbs, a “bunny hopping” gait, urinary incontinence, and/or muscle pain.18,24–26 Clinical signs progress in some dogs to lethargy, tetraplegia, inability to fully open the mouth, dysphagia, and respiratory difficulty. Involvement of esophageal muscle may lead to megaesophagus.27,28 Mandibular paralysis, vomiting, and lethargy were described as the only clinical signs in one affected dog.28 Although ocular lesions are not a major clinical feature of neosporosis, focal chorioretinitis has been reported in some puppies.29 Less often, young dogs develop signs of hepatitis; pneumonia; meningoencephalomyelitis; or myocarditis with arrhythmias, acute onset of respiratory distress, or sudden death.26,27,30,31 Puppies with neuromuscular signs may have subclinical infection of other organ systems.27 In contrast to puppies, adult dogs typically develop polymyositis and/or meningoencephalomyelitis, with a variety of neurologic signs.19,27,32 Although lesions can occur throughout the central nervous system (CNS),27 N. caninum has a predilection for the cerebellum.19 Some dogs can develop cerebellar atrophy.19,33 Disseminated infections that involve the myocardium, liver, pancreas, lungs, skin, and/or eyes can also occur in adult dogs but are less common than encephalitis. In one unusual case, N. caninum tachyzoites were found in the peritoneal fluid of a dog with bacterial peritonitis.34 Physical examination findings in puppies with polyradiculoneuritis-myositis vary from mild ataxia and muscle atrophy to tetraparesis with rigid extension of one or both pelvic limbs and arthrogryposis. Reduced patellar and sometimes other segmental reflexes (including the perianal reflex) are often present.18,24,35,36 Severely affected dogs may be lethargic and exhibit respiratory difficulty, and it may only be possible to open the mouth a few centimeters. Fever is rare.18 Dogs with myocardial involvement may develop acute onset of respiratory difficulty and cyanosis.18,27 Cutaneous involvement is manifested as dermatitis with single or multifocal firm nodules, crusting, and/or ulceration, which can appear at additional sites over time and may or may not be accompanied by other systemic signs of infection.21,37–40 Rarely, dogs with pulmonary involvement are evaluated for cough or respiratory difficulty.41 Neosporosis should be suspected in young dogs (<1 year of age) that develop ascending paralysis and muscle atrophy. It should also be suspected in dogs that develop neurologic (and especially cerebellar) signs or nodular dermatitis, especially in predisposed breeds or dogs treated with immunosuppressive drugs. Diagnosis most often relies on serology or detection of protozoal organisms in body fluids, aspirates, or tissues using light microscopy and/or PCR assays (Table 73-1). Often, antemortem diagnosis is based only on serologic testing because organisms are not easily found. Complete Blood Count, Serum Biochemistry Panel, and Urinalysis As for toxoplasmosis, there are no specific hematologic or biochemical abnormalities that suggest neosporosis. The CBC is often normal, but occasionally mild nonregenerative anemia, mild eosinophilia, or monocytosis is evident.18,32 The serum biochemistry panel reveals increased creatine kinase activity in dogs with myositis.19,23,24,26 Occasionally, increased activity of serum ALT (due to hepatitis or severe myositis) or hyperglobulinemia is evident.23,32 The urinalysis is generally unremarkable. The CSF of dogs with N. caninum meningoencephalitis may be normal or show mild to markedly increased total nuclear cell count (TNCC) (sometimes >1000 cells/µL) and mild to markedly increased CSF protein concentration.19,32 Usually, a mononuclear pleocytosis is present, but occasionally the response is mixed or primarily composed of neutrophils or eosinophils.19,24,32,35 N. caninum tachyzoites are rarely seen in CSF.22,32 Thoracic radiographs in dogs with neosporosis are usually unremarkable but may show a diffuse interstitial pattern in dogs with pneumonia, or evidence of megaesophagus in dogs with neuromuscular signs.18 Abnormalities are rarely detected on abdominal ultrasound examination of dogs with neosporosis. MRI of adult dogs with cerebellar signs associated with N. caninum infection may show moderate to marked bilateral cerebellar atrophy.19 Meningeal contrast enhancement may be present.19,32 Single or multifocal T2-weighted and FLAIR hyperintensities that enhance with contrast on T1-weighted images may be present within the cerebellum or other parts of the brain (Figure 73-2). Mild to moderate heterogenous T2-weighted and FLAIR hyperintensities can also be seen in the masseter and temporalis muscles, which may appear atrophied. FIGURE 73-2 Sagittal T1-weighted postcontrast MRI image from a 4-year-old female spayed Chihuahua with suspected Neospora caninum meningoencephalitis. Multiple poorly defined regions of contrast enhancement were identified in the cerebral cortices (large arrow), and mild meningeal enhancement was evident (small arrow). CSF analysis revealed a mononuclear pleocytosis, and Neospora DNA was detected using PCR in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Neosporosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Features

Physical Examination Findings

Diagnosis

Laboratory Abnormalities

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

Diagnostic Imaging

Sonographic Findings

Advanced Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neosporosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue