Chapter 48 Myocarditis

• Myocarditis is an inflammatory process involving the heart. Inflammation may involve the myocytes, interstitium, or vascular tree.

• Myocarditis has been associated with a wide variety of diseases. Infectious agents (viral, bacterial, protozoal) may cause myocardial damage by myocardial invasion, production of myocardial toxins, or activation of immune-mediated disease.

INFECTIOUS MYOCARDITIS

Bacterial and Other Causes of Myocarditis

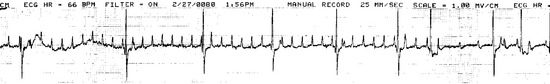

Parasitic agents can also lead to myocarditis. Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites can encyst in the myocardium, resulting in chronic infection. Eventually the cysts rupture, leading to myocardial necrosis and hypersensitivity reactions.1 Neospora caninum can infect multiple tissues, including the heart, peripheral muscles, and central nervous system. Clinical signs associated with noncardiac tissues typically predominate; however, collapse and sudden death has been reported in affected dogs.1 Infestation with Trichinella spiralis is a common cause of mild myocarditis in humans.11 The parasite has been associated with at least one case of canine myocarditis complicated by arrhythmias (Figure 48-1).12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree