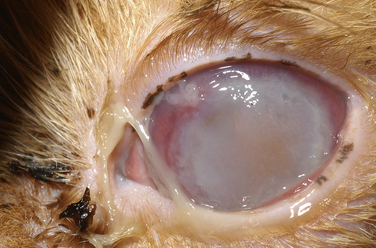

Chapter 40 Mycoplasmas are fastidious bacteria that lack a cell wall. They belong to the class Mollicutes (which translates to “soft skin”), and are the smallest known free-living organisms. Many require sterols for growth, and Ureaplasma species require urea for fermentation. Mycoplasmas measure only 0.3 to 0.8 µm in size. More than 120 different species of Mycoplasma and 7 species of Ureaplasma have been identified. The spectrum of mycoplasma species that infect or colonize dogs and cats is incompletely understood because precise species identification has been difficult (Box 40-1).3–7 Additional mycoplasma species are likely to be discovered with the application of molecular methods in the future. Some Mycoplasma spp. infect multiple host species. Mycoplasmas are often difficult to grow on cell-free media, and some, such as the hemotropic mycoplasmas, have never been successfully cultured in the laboratory (see Chapter 41). The remainder of this chapter refers only to nonhemotropic mycoplasma species. Mycoplasmas are commensal bacteria found widely in association with mucous membranes of all mammalian species. Simultaneous colonization with more than one Mycoplasma species is common. Mycoplasmas have also been associated with keratoconjunctivitis and/or upper respiratory tract disease (URTD) in cats; reproductive disease and urinary tract infections (UTIs) in dogs; and lower respiratory tract disease, skin and soft tissue infections, meningoencephalitis, and arthritis in both cats and dogs (Box 40-2).8–18 Because mycoplasmas are commonly isolated from the upper respiratory and genital tracts of healthy dogs and cats, their role in ocular, upper respiratory tract, and urogenital tract disease has been difficult to determine. Several studies have now identified an increased prevalence of mycoplasmas in cats with conjunctivitis or URTD when compared with healthy cats.13,19,20 Mycoplasmas can act as secondary invaders when other pathogenic viruses and bacteria are present, or when normal host defenses are impaired by factors such as underlying neoplasia or immunosuppressive drug therapy. When mycoplasmas are associated with systemic disease or pneumonia, young animals (less than 1 year of age) are often involved. Some mycoplasma species appear to be more pathogenic than others. For example, evidence has accumulated that Mycoplasma cynos is associated with lower respiratory disease in dogs.21,22 In one study, M. cynos infection was associated with increased severity of canine infectious respiratory disease, younger age, and longer time spent in a kennel.22 Experimental infection with M. cynos leads to respiratory disease in dogs, but infection with Mycoplasma gateae, Mycoplasma canis, and Mycoplasma spumans does not.23 The role of mycoplasmas in feline lower urinary tract disease and lymphoplasmacytic pododermatitis has been investigated using molecular techniques, but no association was found.24,25 In order to colonize mammalian hosts, mycoplasmas must adhere to host cells. Mycoplasma species that infect humans are known to possess specific adhesins, but these have not been well characterized in mycoplasmas from dogs and cats. Invasion of deeper tissues and disease occurs as a result of immunosuppression or disruption of normal host barriers. Some mycoplasmas, such as the human pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae, produce toxins, but whether similar virulence factors are present in mycoplasmas isolated from dogs and cats is unknown. A number of pathogenic mycoplasma species of humans can invade cells, which may contribute to organism persistence and difficulties associated with isolation in the laboratory. Transmission of pathogenic mycoplasmas such as M. cynos may occur in overcrowded environments as a result of close contact or fomite spread. The finding of identical strains in multiple dogs from a kennel environment (using molecular typing methods) supports the concept of transmission between dogs in this environment.26 The extent to which mycoplasmas survive in the environment varies among mycoplasma species and has not been determined for mycoplasmas that infect dogs and cats. Mycoplasma spp. are commonly detected in cats in association with conjunctivitis and URTD. Concurrent infections with other upper respiratory pathogens (such as Bordetella bronchiseptica, Chlamydia felis, and feline respiratory viruses) may contribute to clinical signs. Stressors such as overcrowding and unhygienic conditions may promote proliferation of mycoplasmas and their transmission between cats. Ulcerative keratitis has been reported in association with Mycoplasma infection, but the presence of corneal involvement may reflect the concurrent presence of feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) or other factors that predispose to secondary invasion by Mycoplasma spp. (Figure 40-1). FIGURE 40-1 Ulcerative keratitis in a 4-year-old female spayed Persian. Involvement of feline herpesvirus-1 was suspected, and Mycoplasma spp. was isolated from a corneal swab. The significance of the Mycoplasma infection was unclear, but the ulcer healed after topical treatment with topical ofloxacin and azithromycin drops. (Courtesy of the University of California, Davis, Veterinary Ophthalmology Service.) Virtually all dogs and cats harbor mycoplasmas in their upper respiratory tracts. Fewer than 25% of healthy dogs harbor mycoplasmas in their trachea or lungs. In one study mycoplasmas were detected in tracheobronchial lavage specimens from 21% of 28 cats with pulmonary disease, but not from 18 healthy cats.27,28 Mycoplasmas can be isolated from the lower airways and lungs of dogs and cats with pneumonia, sometimes in pure culture.29 Factors that predispose to the development of mycoplasma pneumonia are not always apparent.30 Clinical signs include variable fever, cough, tachypnea, lethargy, and decreased appetite. Concurrent signs of URTD have been reported in some affected cats.30 Rarely, mycoplasmas can be cultured from the pleural fluid of cats and dogs with pyothorax, in pure culture or in mixed infections with other organisms.31–33 Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma spp. have been found in the semen and urine of dogs with infertility and purulent epididymitis.34 The role of mycoplasmas in reproductive tract disease in dogs and cats is unclear because they are commonly isolated from the urogenital tract of healthy dogs and cats. Large numbers of mycoplasmas (>105 CFU/mL) can occasionally be isolated in pure culture from urine collected by cystocentesis from dogs with prostatitis and lower urinary tract signs.14,34 Dogs with mycoplasma UTIs often have other comorbidities that impair normal urinary defenses, such as urinary tract neoplasia, calculi, or neurologic disease.14 Isolated case reports exist of polyarthritis due to infection with M. spumans or Mycoplasma edwardii (dogs) and M. gateae or M. felis (cats). Synovial fluid analysis usually reveals the presence of large numbers of neutrophils. This may lead to diagnostic confusion with primary immune-mediated polyarthritis. Systemic signs such as lethargy, fever, and inappetence usually accompany lameness. Evidence of immune compromise, such as underlying neoplasia or surgery, young age, or a history of glucocorticoid treatment, has generally been present in dogs and cats with mycoplasma polyarthritis. M. felis has also been isolated from cats with monoarthritis, possibly secondary to bite wound infections.17 Mycoplasmas may gain access to the central nervous system after penetrating wounds, ascending infection from the middle ear, or hematogenous spread. Meningoencephalitis associated with M. felis infection was described in a 10-month-old cat that showed signs of lethargy, fever, a head tilt, nystagmus, and tetraparesis.12 M. felis was isolated in pure culture from the CSF. The cat also had evidence of otitis media-interna at necropsy, but the role this played in development of the mycoplasma infection was unclear. M. edwardii was isolated from the brain of a 6-week-old dog with a sudden onset of seizures.8 Suppurative and histiocytic meningitis was detected at necropsy, in conjunction with evidence of a possible penetrating wound to the skull. Recently, infection with Mycoplasma canis has been associated with some cases of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis and necrotizing meningoencephalitis in dogs,35 which requires further study. Physical examination findings in dogs and cats with mycoplasma infections depend on the organ affected, as well as underlying disease processes that facilitate opportunistic invasion by mycoplasmas. Ocular infections in cats are characterized by serous to mucopurulent ocular discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, and possibly keratitis. Upper respiratory tract infections may result in nasal discharge and sneezing, with or without conjunctivitis. Fever, tachypnea, and increased lung sounds may be present with pneumonia. Urinary tract infections may lead to clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease, such as hematuria or stranguria. Mycoplasma arthritis may be manifested by fever, joint pain and swelling, and sometimes local lymphadenopathy.9–11 Findings on the CBC, serum biochemistry panel, and urinalysis in dogs or cats with Mycoplasma infections are nonspecific and influenced by underlying immunocompromising disease processes. Dogs and cats with pneumonia, mycoplasma bacteremia, and polyarthritis may have a neutrophilia with a left shift and neutrophil toxicity, a degenerative left shift, mild nonregenerative anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and evidence of organ dysfunction such as increased liver enzyme activities and azotemia.9,10,15

Mycoplasma Infections

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Features

Conjunctivitis and Upper Respiratory Tract Disease

Pneumonia and Pyothorax

Urogenital Tract

Arthritis and Bacteremia

Meningoencephalitis

Physical Examination Findings

Diagnosis

Complete Blood Count, Serum Biochemical Tests, and Urinalysis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Mycoplasma Infections

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue