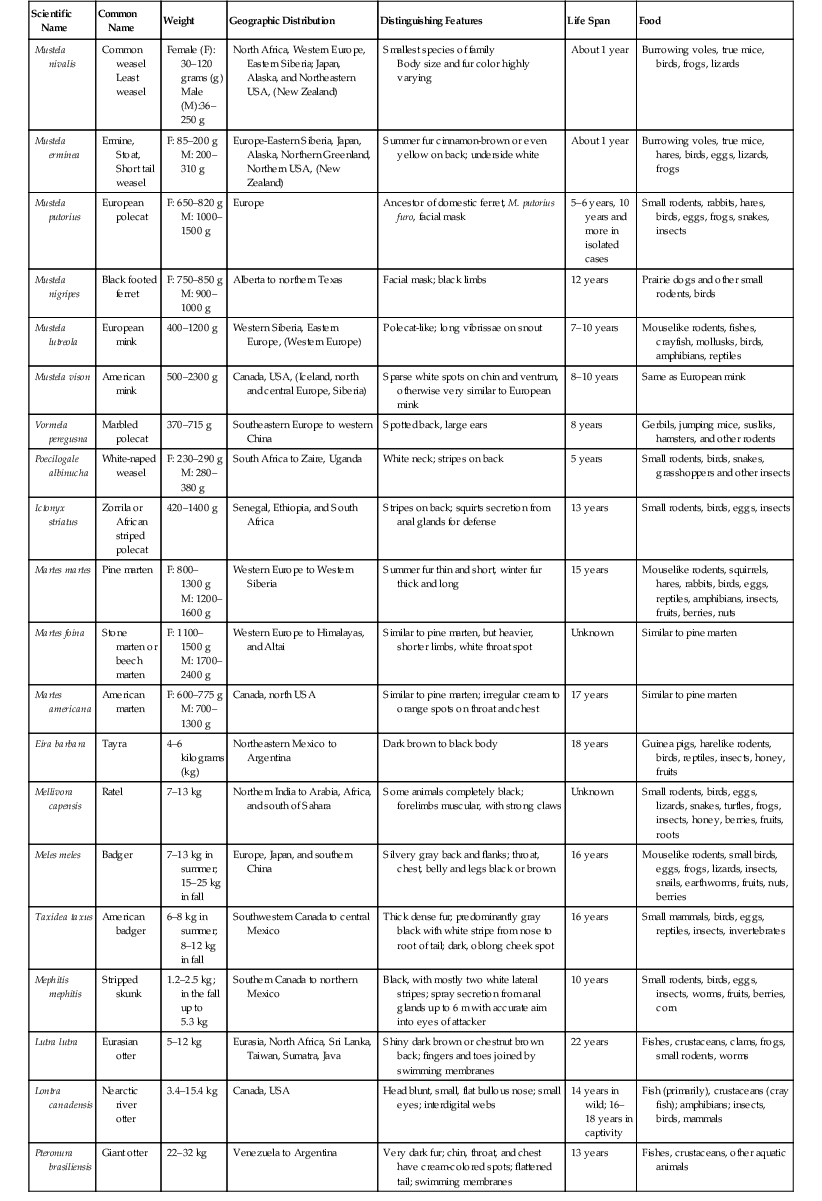

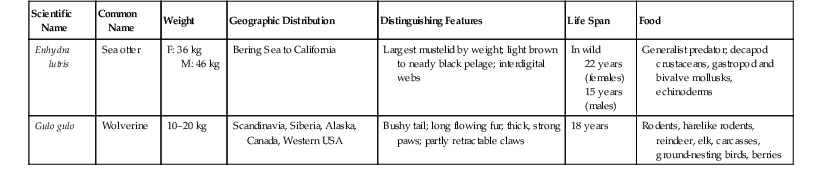

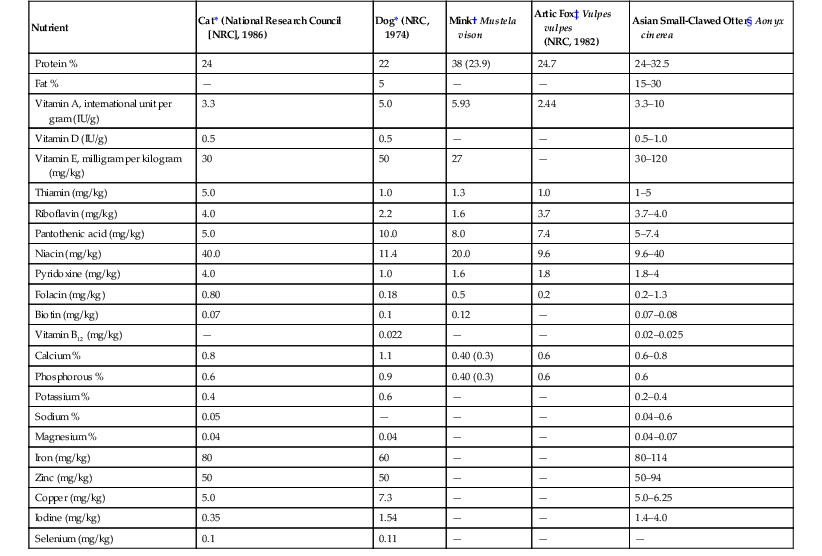

George V. Kollias, Jesus Fernandez-Moran Recent studies have revealed that the Musteloidea emerged approximately 32.4 to 30.9 million years ago in Asia. During the Oligocene, musteloids diversified into four primary divisions: Mephitidae, Ailuridae, Procyonidae, and Mustelidae. Mustelidae arose approximately 16.1 million years ago. The early offshoots largely evolved into the ecologic niches of badgers and martens, whereas later divergences have adapted to other niches, including those of weasels, polecats, minks, and otters.35 Extant mustelids are classified in the order Carnivora, suborder Caniformia, family Mustelidae, and subfamily Mustelinae and Mephitinae. The family Mustelidae currently includes 25 recent genera and approximately 67 species of terrestrial carnivores or piscivores inhabiting all continents except Australia and Antarctica and are also absent in New Guinea, Madagascar and Antarctica. They have been introduced into New Zealand. In the course of evolution, several behavioral adaptations and many physical features have developed, as some species live mainly in the ground (stoat, weasel, polecat) or even partially underground (badger), whereas others are active also above the ground in trees (pine marten). Some have selected marine or fresh water as their preferred habitats most or part of the time (mink, river otter, sea otter). Included in this family are the smallest living carnivore, the common or least weasel, and the largest representatives, the giant and sea otters in water and the wolverine on land. Mustelid body weights range from under 70 grams (g) (least weasel at 19 centimeters [cm] long) to 45 kg (sea otter at 190 cm long). The family Mustelidae includes five subfamilies. The weasel-like carnivores (Mustelinae) represent the group with the greatest number of species, comprising 10 genera with approximately 33 species including weasels (11 species), polecats (3 species), minks (2 species), grison (1 species), and wolverine (1 species). The subfamily Mellivorinae is represented by only a single species, the honey badger or ratel (Mellivora capensis). Subfamily Melinae includes five genera in eight species of badgers represented in Africa, Asia, South America, or wide ranges of northern Eurasia and North America. Skunks (subfamily Mephitinae, recently elevated to Family Mephitidae) are exclusively common in North America. Otters (subfamily Lutrinae) are small to large forms that show the most highly developed adaptations to marine life of all mustelids. They lead an amphibious life and feed mainly on fish or crustaceans. Most mammologists recognize four genera and 13 species.30 Most mustelids have a highly flexible spinal column; the limbs are comparatively short, ending in feet with five digits, and they walk either digitigrade or plantigrade. The claws are not (or only partly) retractable. Mustelids lack the clavicle and cecum. They present the typical carnivore dentition with number of teeth varying from 28 to 40. Developed canine (C) teeth are always present and the last premolar (P) in the upper jaw and the first molar (M) in the lower jaw jointly form the “crushing shears” for processing food. The dental formula of weasels is incisors (I) 3/3, C 1/1, P 3/3, M 1/2 on the upper and lower jaws. In the wolverine the formula is I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/4, M 1/2 upper and lower. Eurasian badger formula is I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/4, M 1/2 upper and lower, and in the members of the Lutra and Lontra genera the formula is I 3/3, C 1/1, P 3-4/3, M 1/2 upper and lower. The pine marten has a dental formula of I 3/3, C 2/1, P 4/4, M 1/2 upper and lower (40 teeth total), which is different from that of other mustelids. Glands may be located in various regions of the body surface. The paired anal glands produce odorous secretions characteristic of the species and used for marking their habitat, sometimes for generations. Some species may spray these secretions over long distances as a method to discourage or harm enemies. In otters, the mandibular salivary glands and lymph nodes lie in the angle of the mandible, whereas the retropharyngeal nodes lie dorsolateral and slightly caudal to the larynx. The thyroid glands of otters are also different from those of other mustelids in that they are long, flat, and tapering, with no isthmus, and closely attached to the trachea. The heart of otters is usually globular with a thick-walled left ventricle and a thin-walled right ventricle. The shape of the heart and thickness of the ventricles should not be confused with ventricular hypertrophy. Otters have a seven-lobed liver. A common hepatic and cystic bile duct joins the duodenum adjacent to the pancreatic duct. The kidneys of otters, like those of cows and cetaceans, are multilobulated. The lungs of otters and badgers are composed of two lobes on the left, three lobes on the right, and an intermediate lobe where the right bronchus terminates.5,15 Mustelids are predominantly solitary, sexually dimorphic mammals (males are 25% larger than females). Smaller mustelid species have high metabolic rates. Males and females come together only during the reproductive period, and social communities generally include the mother and offspring. Table 48-1 summarizes the biologic data of selected mustelids. Members of the family range from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) status Endangered (black-footed ferret) to Near Threatened (wolverine) to IUCN status Least Concern (badger). The family Mustelidae contains numerous fully terrestrial species, two that are semi-aquatic (minks), and a number that are amphibious to fully aquatic (the Lutrinae). The latter have adaptations for the aquatic habits that may be relevant for the clinical management. Underwater vision presents challenges for the mammalian eye: the need for increased sensitivity to light, accommodation of the spectral shift toward the blue-green wavelengths, and modification of the ocular focusing capacity because of refractive differences compared with those in air. Different adaptations for these challenges have been proposed, although visual acuity in water is somewhat reduced in some otter species (i.e., Asian small-clawed otter). Little is known of the importance, sensitivity, and mechanisms of hearing in otters, in the aquatic or the terrestrial environment. Olfaction has been retained as an important sense for aquatic mustelids, largely but not exclusively in support of their activities on land. However, evidence suggests that otters have less complex scent production capacities compared with terrestrial mustelids and that scent production capacity in sea otters may be more poorly developed and less important than in other otter species. These changes probably have resulted from the increased importance of vision and the reduced importance of olfaction in the aquatic environment. The long, lean body of Mustelinae species makes them vulnerable to rapid heat loss on land and in the water. Insulation in aquatic mustelids is achieved by means of a dense underfur that prevents water penetration to the skin while providing buoyancy. Because fur is an efficient insulator, furred aquatic mammals require some means of thermoregulation; in sea otters, thermoregulation is conducted through the enlarged rear flippers. In otters and minks, swimming is the primary means of locomotion. These species demonstrate many adaptations that enhance swimming performance and reduce energy expenditure while in the water: body streamlining, large, specialized plantar surfaces for propulsion, and the ability to remain submerged for extended periods. However, most otters, unlike most aquatic mammals, are capable of quadrupedal locomotion on land, and this is why they are considered morphologically intermediate between terrestrial and aquatic mammals.12 Most species tolerate a wide range of temperature ranges. Temperate and cold-adapted species held outdoors need protection from sunlight when the temperature exceeds 50° F (10° C). Tropical species require heated shelters when ambient temperatures drop below 69° F (20° C). Animals kept indoors should not be exposed to temperatures exceeding 78° F (25° C). It is important to be aware that required temperature ranges vary among individuals as well as between species, so individual animals should be given the opportunity to select a comfortable ambient temperature from a gradient provided in the enclosure. Humidity for indoor enclosures should range from 30% to 70% but may be higher for tropical species. The amount of time individuals held indoors are exposed to light should replicate the natural photoperiod of their native environment, particularly for those species that are expected to reproduce in captivity. Currently, data on the effects of varying light intensity or type of light (fluorescent versus natural) on reproductive behavior are not available; however, a correlation exists between the onset of estrus in northern mustelid species.4 Indoor exhibits should have a negative air pressure of five to eight air changes per hour (for odor control) of non-recirculated air; however, this is not necessarily a requirement and recirculated air may be used in some cases. Fresh drinking water should be provided at all times. Nonfiltered water, contained in pools or moats and used for swimming, should be changed on a regular basis. Even if water is filtered, it should be completely changed periodically. Mustelids should not be given access to pools that have recently been treated with chlorine (levels should be <0.5 parts per million [ppm]). For otters that normally inhabit fresh or brackish water environments, dissolved nutrients should be monitored and water changes performed, as appropriate. It is suggested that the coliform level not exceed 400 colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) (water with a level of 100 CFU/mL is reported to be safe for humans). Filtration should be used in closed pools for otter. Sand filters, pool pumps, charcoal filters, and ozone pressure sand filters have all been used effectively. Drain outlets and filter and skimmer inlets should be covered to prevent furnishings from obstructing them or from otters getting stuck in them. Natural flow-through systems work well in otter exhibits. Water flowing in must be clean and pollutant free. All uneaten food items should be removed from pools on a daily basis. Because minks are highly susceptible to methyl mercury toxicity, pools need to be maintained at a neutral or basic pH (acidic pH enhances methylation of mercury). Controlling of sounds and vibrations that may be detected by mustelids is important to their well-being. Anecdotal reports of loud noises and vibrations of certain amplitude affecting parturition and early kit rearing in mustelids have been published.3,4 Exhibits should be designed to satisfy the physical, social, behavioral, and psychological needs of the species while closely replicating their habitat in the wild. Enclosure size for arboreal and terrestrial mustelids is based on species’ and individual needs (e.g., juveniles versus adults versus geriatric animals). Exhibits that are provided extensive enrichment and are structurally varied may be smaller than exhibits lacking these characteristics. (Note that enrichment items must be chosen carefully, since many mustelid species are prone to chewing and ingesting enrichment parts, putting them at risk of gastrointestinal [GI] foreign body obstruction). Recommended exhibit sizes are based on species size, behavioral repertoire, home range size, daily movements, and activity patterns. Detailed information is given in the Mustelid (Mustelidae) and Otter (Lutrinae) Care Manuals provided by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Small Carnivore Taxon Advisory Group. Animal and human safety must be kept in mind when designing and building mustelid exhibits. Additionally, mustelids are not well suited for free-ranging exhibits because of their uncanny ability to escape. Exhibits must be designed to prevent them from digging, jumping, climbing, or swimming out of enclosures. Outdoor exhibits should have containment perimeters, tops and hotwire 3 to 5 feet (ft.; 1–1.52 meters [m]) installed above ground level to prevent them from climbing and falling. For burrowing species (e.g., badgers), the bottom of the containment fence may need to be buried to a sufficient depth and angled toward the center of the exhibit to prevent escape. For amphibious species (e.g., otters), optimal land-to-water ratios are species dependent. These ratios may need to be changed as exhibit size increases or decreases (e.g., smaller exhibits will require a higher land area proportion within the ratio).3,4 Within the Mustelidae family, food habits vary significantly. Some are strict carnivores (ferrets, weasels, polecats, etc.), some are omnivorous (skunks, badgers or tayras), and some are piscivorous (fish and crustacean eaters such as otters) (see Table 48-1). Mustelids have a relatively simple stomach and a short GI tract and, as mentioned above, no cecum. The more omnivorous species have flattened molars. Captive mustelid species are fed on a great variety of items: commercial dry dog food, mink food, and cat food, and cereal diets mixed with meat, fresh or frozen fish, shellfish, crabs, and crayfish. Fruits, vegetables (carrots, lettuce, green beans, cucumber, collard greens, kale, potatoes, among others), eggs, and live or killed food items (crickets, mealworms, mice, prairie dogs) have also been incorporated into captive diets. Target dietary nutrient values for mustelids are based on several sources. The cat is typically the model species used to establish nutrient guidelines for strict carnivorous animals. The National Research Council (NRC, 2006, for dogs and cats), and Association of American Feed Control Officials (1994, for cats) have provided recommendations. A limited amount of information has been provided by the NRC publication on mink and foxes, which represents the requirements of another mustelid species (Table 48-2). The complete dietary requirements of domestic ferrets are still unknown, so no one particular diet is currently being recommended over another. In the ferret and mink diet, the protein should be of high quality and easily digestible because of their short GI transit time of 3 to 4 hours. Generally, most mustelids need a diet high in good-quality meat protein and fat and low in complex carbohydrates, inclusive of sugars, and fiber. High levels of protein from plant sources have been associated with urolithiasis in mustelids and are therefore undesirable. Food should be offered at least twice a day, and water must be available at all times. When developing appropriate dietary management plans for a specific mustelid species, the following should be considered: feeding ecology, target nutrient values, food items available at zoos, and information collected from diets offered by institutions successfully maintaining and breeding for the species. TABLE 48-2 Nutrient Requirements and Target Nutrient Ranges for Selected Carnivore Species * National Research Council: Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. Washington, DC, 2006, National Academy Press. † Growing and weaning to 13 weeks. Numbers between parentheses are for maintenance (from National Research Council: Nutrient requirements for minks and foxes. Washington, DC, 1982, National Academy Press). ‡ National Research Council: Nutrient requirements for minks and foxes. Washington, DC, 1982, National Academy Press). § Maslanka CS: Asian small-clawed otters: Nutrition and dietary husbandry. In: Nutrition Advisory Group handbook, 1999. Even though some captive mustelids may be gentle with their keepers, all members of this family may be handled with nets, snares, or squeeze cages. Caution must be used while managing wild mustelids, as they have needle-sharp teeth and are agile and aggressive and may inflict severe bites. They are also potential vectors of rabies, so they should be handled with caution. Leather gloves should be used by operators when handling any kind of mustelid, whatever the size. The ferret is best restrained when grasped above the shoulders, with one hand gently squeezing the forelimbs together and the thumb under the animal’s chin. Minks are grasped by the tail with one hand, while the other hand grasps the animal behind the neck, with the thumb and finger around the head. Polecats, ermines, weasels, and martens are better restrained initially with a net when an injection has to be administered by hand. Skunks defend themselves by spraying the secretions of the anal sacs, and they may bite as well. The defensive position assumed by a threatened skunk is hindquarters facing the enemy, feet planted firmly on the ground, and tail straight up in the air. They should be captured with a net from behind a shield of glass or plastic, or the handler should wear goggles and protective rain gear. Larger mustelids such as otters, badgers, and wolverine may be placed in a small squeeze cage for manual injection of a tranquilizer or directly injected by means of a pole syringe or a blowpipe.16 Mustelids are susceptible to stress caused by improper handling and transport. Fresh water and marine otters are particularly susceptible to stress-associated exertional myopathy. Different techniques have been developed for safe management of this species. Only trained personal should handle mustelids, and usually, a combination of physical restraint and chemical restraint is advocated to reduce stress and avoid capture myopathy. The duration of restraint should be brief, and care should be taken to avoid trauma to the oral cavity and limbs. As mentioned above, sea otters are extremely susceptible to stress caused by improper handling and transporting. Different techniques have been developed for the safe management of this species.19,24 Different drugs have been used extensively for the chemical immobilization of mustelids. In most species, dissociative-benzodiazepine– α2-agonists combinations have been used and are highly recommended for induction or short-term anesthesia. Ketamine in combination with midazolam, diazepam, xylazine, medetomidine, or acepromazine (caution: hyperthermia or hypothermia) to improve muscle relaxation. Xylazine, medetomidine, or dexmedetomidine combined with ketamine has been recommended to improve muscle relaxation, and both combinations may be reversed with atipamezole (2.5 milligram [mg] per 5 mg medetomidine, and 1 mg per 8–12 mg xylazine).2,13,27 Tiletamine–zolazepam is another option. Doses ranging from 2.2 to 22 mg/kg have been reported for numerous species of mustelids; higher doses result in prolonged recovery. In otters, the usage of a low dose of tiletamine–zolazepam to achieve anesthetic induction, and supplementation with isoflurane or ketamine (5 mg/kg) for maintenance, has been advocated. Flumazemil (0.05–0.1 mg/kg) may be used to antagonize the zolazepam portion of this combination to hasten recovery, but its usage has not been reported in mustelids other than the Nearctic river otter.38 Drugs and dosages commonly used to provide chemical restraint and sedation in selected mustelids are listed in Table 48-3. These combinations usually provide short periods of chemical restraint (30–45 minutes). If longer periods of anesthesia are needed, inhalation anesthetics (isoflurane and sevoflurane) delivered via an induction chamber, mask, or endotracheal tube is efficient, although the results of chamber induction with inhalation agents may vary and cause excitement in some species. Otters hypoventilate during inhalation anesthesia and require assisted ventilation to prevent hypoxemia and hypercarbia.26 TABLE 48-3 Drugs and Dosages Recommended for Immobilization of Selected Mustelids

Mustelidae

Natural History, Anatomy, and Physiology

Unique Aquatic Adaptations

Outdoor and Indoor Environments

Habitat Design and Containment

Feeding and Nutrition

Nutrient

Cat* (National Research Council [NRC], 1986)

Dog* (NRC, 1974)

Mink† Mustela vison

Artic Fox‡ Vulpes vulpes

(NRC, 1982)

Asian Small-Clawed Otter§ Aonyx cinerea

Protein %

24

22

38 (23.9)

24.7

24–32.5

Fat %

—

5

—

—

15–30

Vitamin A, international unit per gram (IU/g)

3.3

5.0

5.93

2.44

3.3–10

Vitamin D (IU/g)

0.5

0.5

—

—

0.5–1.0

Vitamin E, milligram per kilogram (mg/kg)

30

50

27

—

30–120

Thiamin (mg/kg)

5.0

1.0

1.3

1.0

1–5

Riboflavin (mg/kg)

4.0

2.2

1.6

3.7

3.7–4.0

Pantothenic acid (mg/kg)

5.0

10.0

8.0

7.4

5–7.4

Niacin (mg/kg)

40.0

11.4

20.0

9.6

9.6–40

Pyridoxine (mg/kg)

4.0

1.0

1.6

1.8

1.8–4

Folacin (mg/kg)

0.80

0.18

0.5

0.2

0.2–1.3

Biotin (mg/kg)

0.07

0.1

0.12

—

0.07–0.08

Vitamin B12 (mg/kg)

—

0.022

—

—

0.02–0.025

Calcium %

0.8

1.1

0.40 (0.3)

0.6

0.6–0.8

Phosphorous %

0.6

0.9

0.40 (0.3)

0.6

0.6

Potassium %

0.4

0.6

—

—

0.2–0.4

Sodium %

0.05

—

—

—

0.04–0.6

Magnesium %

0.04

0.04

—

—

0.04–0.07

Iron (mg/kg)

80

60

—

—

80–114

Zinc (mg/kg)

50

50

—

—

50–94

Copper (mg/kg)

5.0

7.3

—

—

5.0–6.25

Iodine (mg/kg)

0.35

1.54

—

—

1.4–4.0

Selenium (mg/kg)

0.1

0.11

—

—

—

Restraint and Handling

Chemical Restraint

Species

Recommended Anesthetic Combination (milligram per kilogram [mg/kg])

Comments/Alternative

American badger

Tiletamine-zolazepam (4.4)

Ketamine (15), xylazine (1)

American river otter

Ketamine (8–12) + midazolam (0.25–5) / Ketamine (3) + medetomidine (0.030) (atipamezole)

Ketamine (10–12) + diazepam (0.3–5) / Tiletamine–zolazepam (4) + flumazenil (0.08)Respiratory depression may occur

Asian small-clawed otter

Ketamine (15–18) + midazolam (0.75–1)

Ketamine (4–5) + medetomidine (0.1–0.12) (atipamezole)

Respiratory depression may occur

Black footed ferret

Ketamine (3) + medetomidine (0.075) (atipamezole)

Ketamine (15) + diazepam (0.1)

Ermine and weasel

Ketamine (5) + medetomidine (0.1) (atipamezole)

Ketamine (3)/ Tiletamine-zolazepam (11–22)

Eurasian badger

Ketamine (5–10) + medetomidine (0.05–0.1) (atipamezole)/ tiletamine–zolazepam (10)

Ketamine (10–16) + xylazine (2–6)/ medetomidine (0.04) + tiletamine–zolazepam (2.5)

Eurasian otter

Ketamine (5) + medetomidine (0.5) (atipamezole)

Ketamine (15) + diazepam (0.5)

Respiratory depression may occur

Ferret

Ketamine (10–30) + xylazine (1–2) or diazepam (1–2) or acepromazine (0.05–0.3)

Tiletamine-zolazepam (22)

Recovery time may be prolonged

Giant otter

Ketamine (8.5–10.6) + xylazine (1.5–2)

Prolonged recovery

Marten

Ketamine (10) + medetomidine (0.2) (atipamezole)

Ketamine (60) + xylazine (12)

Mink

Tiletamine–zolazepam (15) / Ketamine (40) + xylazine (1)

Ketamine (5) + medetomidine (0.1) (atipamezole)

Ratel (honey badger)

Tiletamine–zolazepam (2.2)

Ketamine (6) + xylazine (0.5)

Sea otter

Butorphanol (0.5)/ oxymorphon (0.3)

Fentanyl (0.3) + azaperone (0.25)

Caution: Numerous reports of fatal complications

Stripped skunk

Tiletamine–zolazepam (10)

Ketamine (15) + acepromazine (0.2)

Tayra

Tiletamine–zolazepam (3.3)

Wolverine

Ketamine (5–8) + medetomidine (0.1–0.15)

Ketamine (20) + acepromazine (0.2) ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Mustelidae

Chapter 48