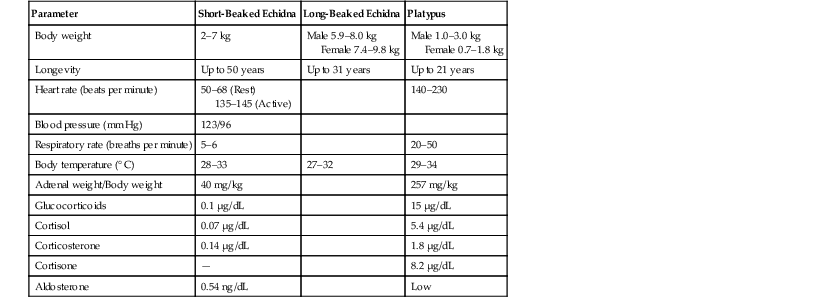

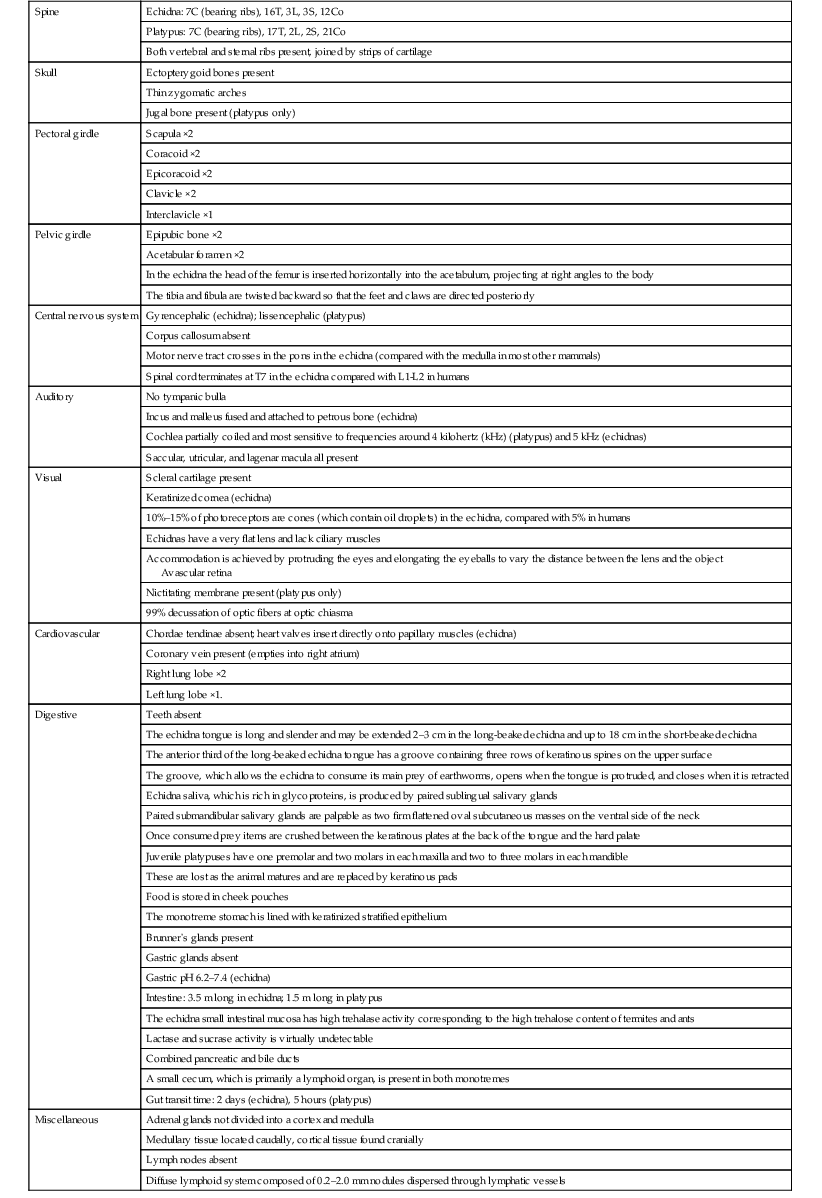

Peter Holz The order Monotremata is unique among mammals, as its members lay shell-covered eggs but nurse their young. The two families in this order are Tachyglossidae, which includes the echidnas, and Ornithorhynchidae, which includes the single species of platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus). Echidnas are terrestrial mammals with a long, tubular snout, powerful claws, and spines that cover the tail and dorsal surface of the body. The spines are firmly attached to the skin and cannot be pulled out as in the case of porcupine spines. Fur is present between the spines and over the belly. Three species of echidna exist. The short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is divided into five subspecies: (1) T. a. acanthion from the Northern Territory, northern Queensland, inland Australia, and Western Australia, (2) T. a. aculeatus from eastern New South Wales, Victoria, and southern Queensland, (3) T. a. lawesii from New Guinea, (4) T. a. multiaculeatus from South Australia, and (5) T. a. setosus from Tasmania. The two species of long-beaked echidna are larger and have fewer, shorter spines and thicker fur compared with short-beaked echidnas. Zaglossus bartoni has five claws on the front foot, and Zaglossus bruijnii generally has only three. Both are found in New Guinea only.1 The platypus is a streamlined, fur-covered aquatic mammal, with a distinctive bill, webbed feet, and a broad flat tail. It is found only in Tasmania and along the east coast of mainland Australia.4 The short-beaked echidna and platypus are both listed as common, whereas both species of long-beaked echidna are classified as endangered because of land clearance and hunting. See Tables 32-1 and 32-2. Short-beaked echidnas and platypuses are pentadactylous, with echidnas having strong front feet and large pectoral muscles adapted for digging. When approached, the echidna will attempt to bury itself into the ground, rolling into a partial ball with its head tucked under its body and leaving only its spine covered dorsum exposed. This is facilitated by contraction of the panniculus carnosus, which also exists in the platypus, a large muscle under the skin of the back and sides. Platypus fur is waterproof and has a hair fiber density of 600 to 900 hairs per square millimeter (hairs/mm2) and traps air for insulation. The platypus has no subcutaneous fat (unlike the echidna) but does store fat in its tail, which makes up 40% of its total body fat. Platypus males possess a sharp spur on each hindlimb, and the spur is connected to a venom gland located in the upper thigh region. The spur is covered by a blunt sheath that erodes away by 9 to 12 months of age. A fleshy collar is present at the base of the spur until about 18 months of age. Spurring and envenomation, although not fatal to humans, is extremely painful and has been known to kill mice, dogs, and other platypuses. Platypuses are more aggressive and their venom more potent during the breeding season (August to October). The venom gland also increases in weight from less than 5 grams (g) to almost 10 g. Therefore, extra care is required when handling these animals during this period. Venom is only produced by sexually mature males from about 4 years of age. Females have a rudimentary spur sheath that is lost around 8 months of age. The spurs are likely used to settle territorial disputes during the breeding season. Generally, only male echidnas have spurs, which range in length from 4.3 to 15 mm, on their hindlimbs (although some females may have small spurs <2 mm long).9 Until recently, these were believed to not contain venom. However, new research has found that these spurs connect to a crural gland that contains proteins similar to those found in platypus venom.10 At this stage, it is unknown if the echidna “venom” is toxic to humans, but echidnas do not strike out with their spurs the way platypuses do. The echidna’s beak and the platypus’s bill are equipped with a number of sensitive electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors, which may be used to locate invertebrate prey. The short-beaked echidna has around 400 mucous glands around the snout tip and nostrils. A quarter of these contain sensory nerve terminals. Each sensory gland is surrounded by several noninnervated glands. Approximately seven sensory glands exist per square millimeter. In the long-beaked echidna, all mucous glands are innervated and are found at a density of 12 per square millimeter. Platypuses have around 40,000 receptors, at a density of 30 per square millimeter, arranged in parallel rows from the tip of the bill to the frontal shield, possibly to aid in assessing prey direction. They may detect weak electric fields down to 1.8 (mVcm-1). Monotreme snouts contain push rods, which are believed to be mechanoreceptors (up to 60,000 in the platypus bill, most densely congregated along the border of the upper bill). Each push rod is around 300 micrometers (µm) long and 50 µm wide, with a dome-shaped tip around 25 µm across. As many as 30 to 40 push rods may be present per square millimeter of skin. The olfactory bulb represents 3.1% of brain volume in the echidna compared with 0.8% in the platypus, and the echidna has 13 times more olfactory nerve fibers. The echidna’s prefrontal cortex occupies 50% of the cerebral cortex, which is likely related to the processing of olfactory information. At the back of the tongue of the platypus are two grooves lined with sensory cells, which are probably involved in taste sensation, and a Jacobson’s organ, which consists of two pouches in the roof of the front part of the mouth. Echidna metabolic rate is one third (in platypuses, half) and oxygen requirements are less than half that of an equivalent-sized dog or cat. Echidnas may hibernate for 6 to 28 weeks, with brief spontaneous arousal every 9 to 12 days, when ambient temperature drops below 12° C. Their body temperature may drop to 4° C, heart rate may decline to 4 to 7 beats per minute (beats/min) and respiratory rate decreases to 0.3 breaths per minute. The echidna thermoneutral range is 20° C to 30° C. Long-beaked echidnas do not appear to hibernate. Monotremes are more susceptible to hyperthermia than to hypothermia. Short-beaked echidnas are unable to sweat or pant, but long-beaked echidnas and platypuses have abundant sweat glands. Platypuses also have two scent glands in the cervical region. Echidnas should be provided with a natural soil substrate over a layer of mesh to prevent their attempts to dig out. They must never be kept on concrete surfaces. Alternatively, the walls may be dug down to a depth of 50 centimeters (cm). Peripheral walls should be smooth, solid, and vertical to a height of at least 50 cm. Overhanging structures should be removed, as echidnas may use them to climb out. In the wild, echidnas are solitary. They have home ranges rather than territories, which vary from 45 to 65 hectares (ha). In captivity, they may be housed together as long as a minimum of 5 square meters (m2) of floor space is provided for each animal. In the hospital environment, echidnas may be kept in smooth plastic tubs containing straw or shredded paper to provide shelter and security. Care must be taken to eliminate sharp edges or cavities, as the echidna could damage its beak on these. Wire cages are unsuitable, but plastic garbage bins may be used for short-term confinement. As echidnas are prone to hyperthermia, it is important to provide shelter from heat. Platypuses require fresh water, for feeding and exercise, and a tunnel system connected to one or more nest boxes. The water needs to be filtered to keep it clean and is commonly replaced at weekly intervals. Pool walls should be 1 to 1.2 m high and at least 0.5 m above the water level to prevent escapes and should contain partially submerged branches and overhanging ledges. Tunnels may be made of marine ply or plastic pipes and should have hatches every meter or so to allow access to the animal. Nesting material such as grass and leaves should be placed in the water during breeding season. Nest boxes may be made of wood, or the platypus may be provided with an area of soil for tunneling and for excavating its own nest. When an area of soil is used, clay soil containing fibrous vegetable matter should be used to prevent possible cave-ins. Platypuses, like echidnas, are cold tolerant but not heat tolerant. Air and water temperatures must be maintained below 27° C. Platypuses are solitary in the wild. Their home ranges vary from 0.2 to 7.3 km, with some overlap of females and subadults but less of males. In captivity, female–female pairs have been housed together. Male–female pairs should be housed in separate quarters. Adult males should never be housed together. Short-beaked echidnas consume predominantly ants and termites (generally preferring termites, as they are more digestible, have higher water content, and live in larger colonies) but will eat other invertebrates such as earthworms and the larvae of beetles and moths. Long-beaked echidnas consume mainly earthworms but will also eat small centipedes, scarab beetle larvae, lepidopteran larvae, and subterranean cicadas. Platypuses consume aquatic invertebrates such as freshwater crayfish, beetles, midges, snails, crustaceans, and caddisfly and mayfly larvae (Trichoptera spp. generally making up over half the diet). Foraging is mainly nocturnal and lasts, on average, 10 to 12 hours per day. Food consumption is 13% to 28% of body weight but may increase to 100% during lactation. They prefer cobbled substrates and avoid mud. Dives usually last between 30 and 140 seconds, but platypuses may remain submerged for up to 10 minutes. Heart rate drops during dives from a range of 140 to 230 to a range of 10 to 120 beats/min. Platypuses usually forage in pools less than 5 m deep, with few dives going deeper than 3 m. Because of the difficulty in obtaining a regular supply of ants and termites, short-beaked echidnas are generally maintained on an alternative diet based on minced meat. Wild echidnas usually take to this diet within a few days. If not, they may be encouraged to accept it by adding formic acid or “paw paw” to the diet. Echidnas are fed food that is 2% to 5% of their body weight daily. Although they have been successfully maintained on this diet, obesity is common, breeding success is low, and fecal consistency is quite variable compared with wild echidnas. Some institutions provide a breeding (high-fat) diet and a maintenance (low-fat) diet, although evidence that this is better than feeding a constant diet all year round does not exist. Recent research has found that vitamin D levels in the blood of echidnas held at three captive facilities were much higher than in wild ones (335.5 nanomoles per liter [nmol/L], 104.0 nmol/L and 187.2 nmol/L in captive echidnas compared with 24.7 nmol/L in wild echidnas). The health effects are not known, but altering the diet reduced serum vitamin D to wild levels.13 A suggested echidna diet is given in Table 32-3. TABLE 32-3 Echidna Diet: Amount per Animal g, Gram; mL, milliliter.

Monotremata (Echidna, Platypus)

Biology

Taxonomy

Unique Anatomy and Special Physiology1,2,4,12

Special Housing Requirements7

Feeding

Free-Ranging Diet1,4

Captive Diet2,12

Ingredient

Short-Beaked Echidna Maintenance Diet

Short-Beaked Echidna Breeding Diet

Water

70 mL

70 mL

Minced meat

100 g

110 g

Raw egg (no shell)

24 g

26 g

Glucose monohydrate

45 g

18 g

Bran

17 g

18 g

Olive oil

9 g

14 g

Calcium carbonate

1 g

1 g

Fly pupae

7 g

7 g

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Monotremata (Echidna, Platypus)

Chapter 32