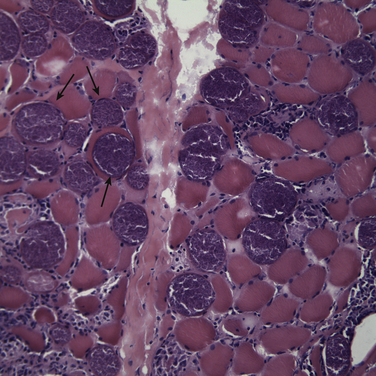

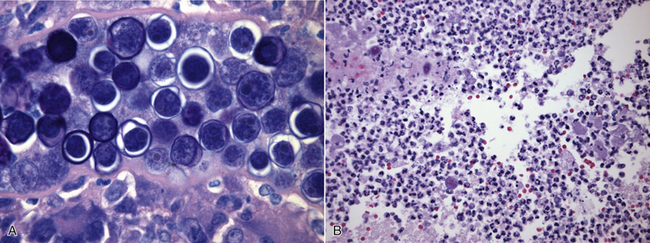

Chapter 83 Besides the systemic protozoal infections described in Chapters 72 to 78, other systemic protozoal infections of dogs and cats include sarcocystosis, amebiasis, rangeliosis, and theileriosis. These are uncommon causes of disease when compared with the other protozoal infections described in this book and are briefly reviewed here. Some have been recognized relatively recently and the life cycle and pathogenesis of these pathogens are not fully understood. Sarcocystosis is caused by Sarcocystis species, which are coccidian parasites that resemble Toxoplasma and Neospora and have a life cycle that involves intermediate and definitive host species. After ingestion of oocysts, organisms replicate in the intermediate host, forming schizonts, usually in endothelial cells. Merozoites are released from the schizonts and ultimately encyst in tissues as a sarcocyst which contains bradyzoites. On ingestion of tissues from the intermediate host by the definitive host, bradyzoites are released from sarcocysts and replicate in the small intestine, with formation of oocysts. The oocysts are then excreted in feces. Dogs are definitive hosts for numerous species of Sarcocystis, but the life cycles of these Sarcocystis species are incompletely understood.1 Sarcocystis canis can cause hepatitis, encephalitis, dermatitis, and pneumonia in dogs, with most reports involving puppies.2–6 Sarcocystis neurona is an unusual species with opossums as definitive hosts and several other animal species as intermediate or aberrant hosts, including dogs, cats, marine mammals, and horses.7,8 There are rare reports of severe S. neurona–like infections in dogs and cats, usually with central nervous system signs associated with the schizont stage.9,10 An unnamed Sarcocystis species has been identified as a cause of systemic illness and myositis in dogs.11 Dogs infected with this Sarcocystis species have shown signs of fever, lethargy, anorexia, thrombocytopenia, and increased liver enzyme activities, followed by development of generalized muscle stiffness, muscle atrophy, and increased CK activity. These clinical signs can resemble a systemic immune-mediated disease. Large numbers of sarcocysts are found in muscle biopsies, with an associated inflammatory and necrotizing myopathy (Figure 83-1). Treatment of one dog with decoquinate led to resolution of signs of myositis. FIGURE 83-1 H&E stained cryosection of a biopsy from the deep digital flexor muscle of an 11-year-old male neutered golden retriever with myositis showing numerous myofibers containing large and encapsulated parasite cysts that were confirmed to be Sarcocystis (200× magnification). (From Sykes JE, Dubey JP, Lindsay LL, et al. Severe myositis associated with Sarcocystis spp. infection in 2 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1277-1283.) Rangelia vitalii and Theileria species are piroplasms that resemble Babesia species and are probably transmitted by ticks. Rangelia vitalii has been identified only in dogs from southern Brazil. It causes a disease characterized by fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, icterus, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and cutaneous and mucosal hemorrhages with hematemesis and bloody diarrhea.12,13 Locally the disease has been referred to as “nambiuvú” (“bloody ear”) because of extensive bleeding that can develop on the outer surface of the pinnae.12 Rangelia vitalii replicates in erythrocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and capillary endothelial cells and can be found in aspirates of reticuloendothelial tissues. Treatment with a single dose of diminazine was effective in the early stages of disease in experimentally infected dogs,13 but several naturally infected dogs died despite this treatment.12 Treatment with a combination of doxycycline, imidocarb dipropionate, and prednisone was effective in other studies.14 A Babesia microti–like small piroplasm (also known as the “Spanish isolate” or Theileria annae) has been identified in dogs in Europe,15,16 and a Theileria species has also been detected in dogs in South Africa.17 The extent to which Theileria parasites cause clinical disease in dogs and cats requires further study. Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia mandrillaris are amoebae that can rarely cause granulomatous meningoencephalitis, nephritis, and/or pneumonia in dogs18–25 as well as humans.26 Other organs may also be affected, such as the heart, pancreas, and lymph nodes.21 Affected dogs are febrile and show a variety of neurologic signs, with CSF pleocytosis. Diagnosis is usually based on finding amoebae in tissues with cytology or histopathology (Figure 83-2). Specific PCR assays have been described that can specifically identify the amoeba species involved. Treatment is difficult but in humans is usually with a combination of antiprotozoal and antifungal drugs. FIGURE 83-2 A, Histopathology of the kidney of a 2-year-old male great Dane with disseminated Balamuthia mandrillaris infection. Protozoal cysts are present within the renal tubules. Trophozoites were also present within the renal parenchyma (not shown). B, Necrotizing encephalitis with intralesional B. mandrillaris trophozoites. Cysts were also found in the brain (not shown). 1000x magnification; H&E stain (A, From Foreman O, Sykes J, Ball L, et al. Disseminated infection with Balamuthia mandrillaris in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:506-510.)

Miscellaneous Protozoal Diseases

Miscellaneous Systemic Protozoal Infections

Sarcocystosis

Rangeliosis and Theileriosis

Systemic Amebiasis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree