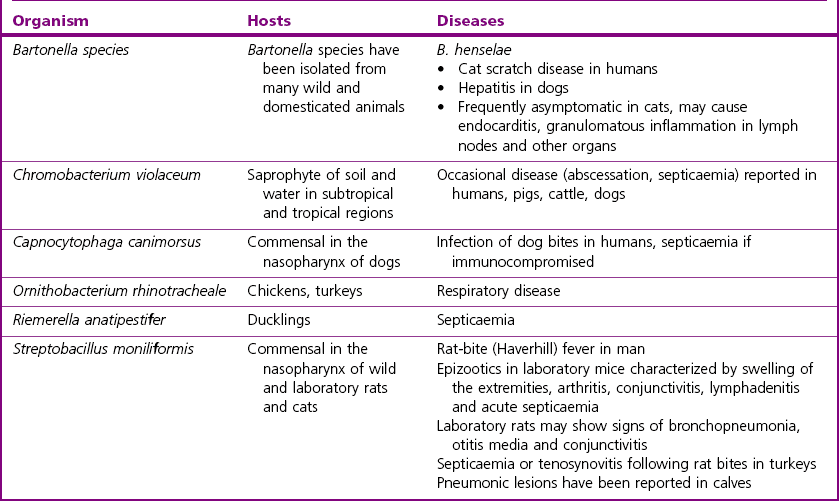

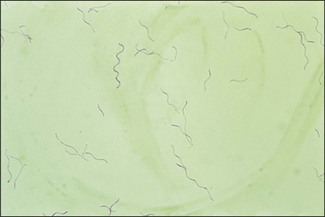

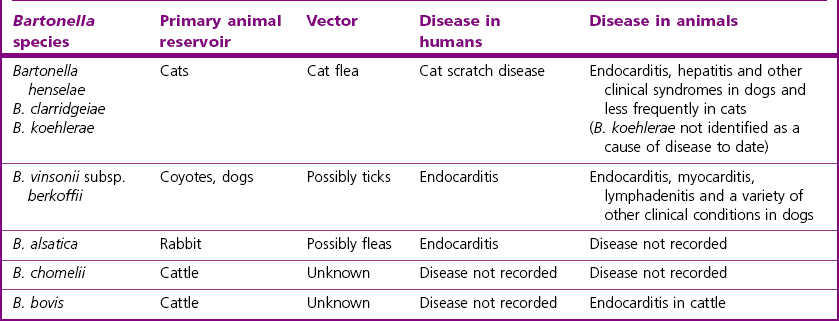

Chapter 32 These bacteria, not included in any other pathogenic groups, are not commonly isolated but may have importance in either animal or human disease, or as zoonotic infections. The habitats, host species and diseases caused by these species are given in Table 32.1. There are 25 species described in the genus Bartonella, present in a wide range of animals and man. The principal pathogen in the genus is Bartonella henselae, which has an animal reservoir, and is the causative agent of cat scratch disease in humans. Several other species are associated with disease in humans and are increasingly reported in association with disease in domestic animals. Bartonellae which have been isolated from domestic animals and their associated clinical conditions are summarized in Table 32.2. Table 32.2 Bartonella species detected in domestic animals, their vectors and associated diseases in humans and animals Bartonella species have been isolated from the blood of many domestic animals as indicated in Table 32.2. Bartonella henselae is carried by domestic and wild cats. Co-infection with a number of Bartonella species has been shown in cats and experimental infection with one species does not confer protection against heterologous challenge (Breitschwerdt 2008). In humans, as in cats, the prevalence of infection is low in northern latitudes and higher in warm and humid regions. Cats may be bacteraemic for weeks to months with kittens being most likely to show prolonged bacteraemia. Transmission of infection from cat to cat is via the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis). Transmission to humans is usually through a scratch from a cat and less frequently from a cat bite. It is likely, although not definitively proven, that the method of transmission is through contamination of the scratch by infected flea faeces adhering to the claws of the cat. The organism is intracellular and is found in red blood cells and vascular endothelium. It appears that B. henselae invades haemopoeitic progenitor cells in humans following infection and that this results in the presence of the organism in circulating red blood cells (Mändle et al. 2005). Although Bartonella species typically cause no disease in cats, cases of endocarditis, lymphadenitis and abscessation in liver and spleen have been reported (Breitschwerdt 2008). Endocarditis has been documented in dogs due to B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, B. clarridgeiae and B. quintana, (Chomel et al. 2006) and also in cattle due to B. bovis (Maillard et al. 2007). Bartonella henselae causes hepatitis in dogs and was associated with chronic arthropathy and presumptive vasculitis in horses (Jones et al. 2008). In tissues, Bartonella organisms stain well with silver stains such as the Warthin–Starry stain. Bartonella species can be difficult to isolate but B. henselae can be isolated from the blood of bacteraemic cats using conventional blood culture systems, although blind subculture onto solid media is required as the organism produces little or no CO2 (Sander 2005). Solid media must be supplemented with 5–10% sheep or rabbit blood. Chocolate agar can be used also. Cell lysis by centrifugation or freezing of the blood sample prior to culture, improves recovery of the organism. Cultures are incubated at 35–37°C for at least four weeks. Isolation from tissue specimens from affected people is usually unsuccessful although isolation rates have been improved by the development of a liquid growth medium (Chenoweth et al. 2004). Colony morphology is variable on primary isolation and colonies are whitish-cream and may be small and smooth or rough and irregular. They are usually adherent and deeply embedded in the agar. Diagnosis of disease is frequently dependent on serological tests with IFAT and ELISA being most widely used. Seroconversion in people and animals such as dogs can be demonstrated and is useful for diagnosis in conjunction with disease signs. Serology in cats is not useful for the diagnosis of disease as cats are frequently asymptomatic. In addition, serology cannot be used to predict bacteraemia as bacteraemic cats may be seronegative (Breitschwerdt 2008). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing can be performed using agar dilution or E-test methods (Dörbecker et al. 2006). The reservoir is the nasopharynx of rats and possibly of small carnivores. Humans can acquire the disease rat-bite fever from the bite of a laboratory rat but it is most common in children. Historically the condition was associated with poverty and rat-infested accommodation but the increasing popularity of keeping rats as pets means that disease is now seen in the owners of such pets and in pet shop personnel (Elliott 2007). The organism has been demonstrated in the mouth of dogs, which had known contact with rats but the importance of dogs as a source of infection for humans is not known (Wouters et al. 2008). The incubation period is usually one to four days and clinical signs include fever, headache, rash on hands and feet, and later polyarthralgia in about two-thirds of patients. The bite wound usually heals well but the disease can develop into a chronic relapsing illness. Transmission in Haverhill fever (Haverhill, Massachusetts) is by the ingestion of contaminated milk or water to which rats have had access. The clinical signs in Haverhill fever are similar to those of rat-bite fever but gastrointestinal and respiratory signs are more common. ‘Spirillum minus’ (Fig. 32.1) is another cause of rat-bite fever in man but this bacterium does not affect animals.

Miscellaneous Gram-negative bacteria

Bartonella species

Natural Habitat

Pathogenicity

Laboratory Diagnosis

Streptobacillus moniliformis

Natural Habitat and Pathogenicity

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine