Chapter 26 Minerals and Stork Nutrition

Storks are medium-sized to large waterbirds belonging to the family Ciconiidae, within the avian order Ciconiiformes alongside herons, ibises, and spoonbills. Storks are widely distributed in tropical, subtropical, and temperate wetlands, although many may live and feed where water is scarce. Nineteen species are recognized; all have long bills, necks, and legs; and the largest members of the family are among the largest flying birds. A male marabou (Leptoptilos crumeniferus) may be 152 cm (61 inches) tall and weigh 8.9 kg (18.6 lb). By contrast, Abdim’s stork (Ciconia abdimii) measures just 75 cm (30 inches) and weighs 1.3 kg (2.8 lb).6

Some species are gregarious and form large flocks, but most habitually forage alone, especially outside the breeding season. Storks are monogamous and mostly nest in trees. Chicks are nidiculous, initially with little feathering and just a coat of down. They are cared for and fed typically by both parents with food that is regurgitated onto the floor of the nest. Body growth is initially rapid, then slows after approximately 3 weeks as the flight feathers start to emerge; fledging takes place between 50 and 100 days depending on size, with larger species taking longer to mature. Accurate details of reproductive success are limited to a few species but likely range from one young per pair in a year in the larger species, to a maximum of three in the smaller species. The white stork (Ciconia ciconia) in Europe, probably the most closely monitored, has an average success of about two young successfully fledged per pair, per year.6

Although only seven species are considered under threat, most wild populations are fragmented and struggling.14 Conservation efforts coordinated through the Storks, Ibis and Spoonbills Specialist Group identified several priorities, including the promotion of captive breeding as a means of building assurance populations.16,27,28

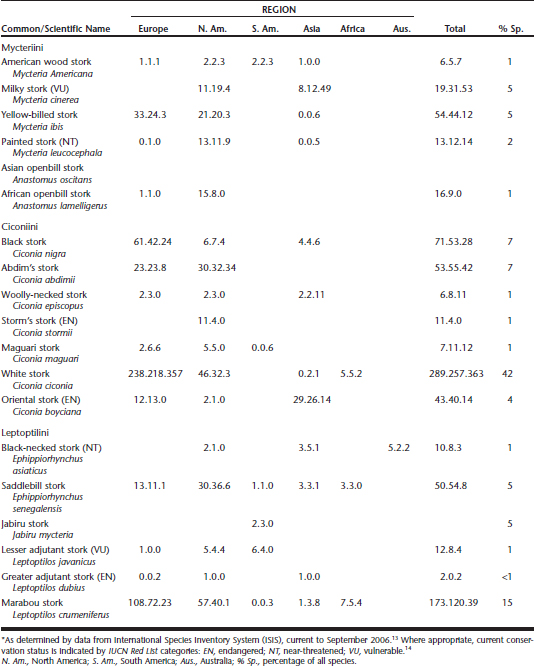

A census conducted by questionnaire in 1987 found all species except Storm’s stork (Ciconia stormii) were present in zoos, although only four species had world captive populations greater than 100 individuals.22 The Stork Interest Group was formed to develop programs for some of the rarer species, using experience gained from the breeding success of these more common species. Data current to September 2006, maintained by the International Species Inventory System (ISIS), once again indicated that all but one species, in this case the Asian openbill stork (Anastomus oscitans), are present in zoos (Table 26-1). Even accepting that the ISIS data may be incomplete because of the rapidity with which animal inventories may change, that delays may occur in transaction records being logged, or that not all zoos worldwide are members of ISIS, the number of species with world populations greater than 100 individuals is still only seven.13

Significant advances in several aspects of husbandry, including enclosure design and holding birds in appropriate social groupings, have increased the number of successes, significantly the Storm’s stork at the Zoological Society of San Diego.* Nonetheless, evidence of reproductive difficulties is more compelling given that eight of the species had populations of 25 or less individuals and 10 species had not recorded any breeding activity in the previous 6 months.13 Chicks that do hatch are not without problems, as shown by the experience with two lesser adjutant stork (Leptoptilos javanicus) chicks hatched at the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bronx Zoo. The chicks were parent-reared and fed diets comprising whole rodents and a supplemented meat mixture containing 2.5% calcium on a dry matter (DM) basis, but both still developed leg bone and beak lesions, which responded favorably to high calcium supplementation.1

Food availability may be the most important limiting factor in most aspects of wild stork ecology, including distribution, longevity, breeding success, and population numbers.14 Thus, it is not an unreasonable assumption that nutritional factors may well underlie captive health and successful reproduction in these altricial, rapidly growing species.

FEEDING MORPHOLOGY, STRATEGY, AND DIGESTION6,26

All stork species are exclusively carnivorous, with plant matter ingested only accidentally along with prey (Table 26-2). The bill is comparatively large, with the shape variable from one genus to another according to feeding habits. The four species of Mycteria are specialist feeders on aquatic prey, taking mostly small to medium-sized fish (typically 3-30 cm [1.2-12 inches] in length) but also some crustaceans, amphibians, and small reptiles. All have a long, tapered, slightly decurved bill with sensitive parts at the tip that allow the stork to fish in conditions that for many other species would prove impossible. Prey detection and capture are based on touch rather than vision because the species frequent shallow, muddy waters or mudflats. Milky storks (Mycteria cinerea) feed largely on mudskippers (Periophthalmus), sometimes by immersing the whole bill and head in mud.

Table 26-2 Prey Items Recorded in Diets of Free-Ranging Storks

| Adult | Chicks | |

|---|---|---|

| American wood stork | Fish21 | Mainly fish (including killifish Molliensia)17 |

| Milky stork | Fish, mudskippers (Periophthalmus spp.)6,21 | |

| Yellow-billed stork | Fish21 | |

| Painted stork | Fish21 | Water snakes46 |

| Asian openbill stork | Freshwater snails (Pila spp.), bivalve molluscs6 | |

| African openbill stork | Freshwater snails (Pila spp.), bivalve molluscs6,12,40 | |

| Black stork | Fish, frogs21 | Fish (particularly Salmo trutta), frogs, reptiles, insects, moles11 |

| Abdim’s stork | Insects (particularly locust swarms, caterpillars of armyworm moth Spodoptera exempta)6 | Toads (Bufo spp.), grasshoppers (Oedaleus spp.)7 |

| Woolly-necked stork | Fish, frogs, snakes, lizards, insects, marine invertebrates15,21 | |

| Storm’s stork | Fish, frogs, snakes, lizards, insects21 | |

| Maguari stork | Frogs, fish, reptiles, insects, crustaceans, small mammals, eggs and young of marsh-nesting birds18 | Eels, fish, earthworms18 |

| White stork | Frogs, earthworms, mice, insects, fish21 | Insects (particularly Orthoptera, Coleoptera), molluscs, and vertebrates45 |

| Oriental stork | Frogs, earthworms, mice, insects, fish21 | |

| Black-necked stork | Fish (particularly catfish), frogs, coots, ducks31,35 | |

| Saddlebill stork | Fish, frogs20 | Fish (particularly lungfish Protopterus aethiopicus and catfish Clarias spp.)20 |

| Jabiru stork | Frogs, fish, snakes, snails, insects18,20 | |

| Lesser adjutant stork | Fish, frogs19 | Frogs1 |

| Greater adjutant stork | Carrion (including buffalo vertebral column and offal), fish, frogs, reptiles (including flapshell turtle Lissemys punctata), ducks, and bone19,37,42 | |

| Marabou stork | Carrion, fish, frogs21 |

The genus Ciconia contains the most familiar storks. All members have medium-sized to large bills, which are probably the least impressive of the family. They are extremely adaptable birds that take many different types of prey in varied habitats, and their bills are thus suited to rather general foraging habits. Abdim’s stork may be considered an exception to the “generalist” tag because it is habitually observed in large feeding flocks feasting on swarms of locusts or armyworm caterpillars (Spodoptera exempta). In many parts of Africa, together with the European white stork, they are known as “grasshopper birds.” The typical foraging method consists of stalking, by walking slowly while actively looking, then jabbing with bill once prey is sighted.

The genera Ephippiorhynchus and Jabiru feed mostly on fish of up to at least 500 g and will also feed on other aquatic species, both vertebrate and invertebrate. These species tend to walk rapidly through shallow water to disturb prey, then make jabbing motions to catch items with bills that are very long, pointed, and slightly upturned. However, the largest bills in the Ciconiidae belong to members of the genus Leptoptilos, and two species, marabou and greater adjutant storks (L. dubius), are notable scavengers regularly feeding on carrion, a feeding preference not shared by any other stork. Although the bills are large (almost 35 cm [14 inches] in the marabou), they are also heavy and ineffective at dismembering carcasses. Nonetheless, they may accommodate large quantities of meat whole (up to 1 kg [2.2 lb]) and are serious predators, consuming a diverse range of live prey, including both young and adult birds. Large bones may also make up a portion of diet (Figure 26-1).

Fig 26-1 A bone eaten by free-ranging, greater adjutant stork (Leptoptilos dubius). (See Color Plate 26-1.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree