Chapter 9 Microbiology of the Ear of the Dog and Cat

Otitis Externa

Microclimate of the External Ear Canal

The relative humidity of the external ear canal in one study of 19 dogs was 80.4%. This was stable through the day, rising only 2.3%, compared with the 24% rise in the humidity of the external environment. However, this increase in average humidity from a relatively high baseline may predispose the canal epithelium to becoming overhydrated and macerated, creating a more ideal environment for bacterial proliferation.

Cerumen coats the lining of the external ear canal. It is composed of lipid secretions from the sebaceous gland and apocrine (ceruminous) glands mixed with sloughed epithelial cells. The lipid content of cerumen from a normal ear canal of a dog can vary widely (18.2% to 92.6%), as does the type of lipid within the cerumen. The types of cerumen lipids found in normal dog ears were cholesterol, 100%; cholesterol esters, 93.8%; free fatty acids, 93.8%; fatty aldehydes, 93.8%; waxes, 93.8%; triglycerides, 68.8%; lecithin, 56.3%; and sphingomyelin, 18.8%. The methodology used in the study was not able to detect small amounts of lipids; therefore this list of lipids accounts for only the major lipids found in the canine ear canal.1

Microbiology of the External Ear Canal

Common diagnostic tests used to evaluate an animal with ear disease include otoscopy, cytology, and bacterial culture and sensitivity. Since the normal ear canal is not a sterile environment, cytologic results, as well as results from culture and sensitivity testing, must be viewed in conjunction with information obtained from a thorough otoscopic examination. On otoscopic examination of the normal ear canal, a small amount of yellowish-brown wax may be seen. There should be no erosion, ulceration, or inflammation of the epidermal lining. The ear canal should be able to accommodate an average-size otoscopic cone without undue pressure on the sides of the canal. The tympanic membrane should be easily visualized in a willing patient.

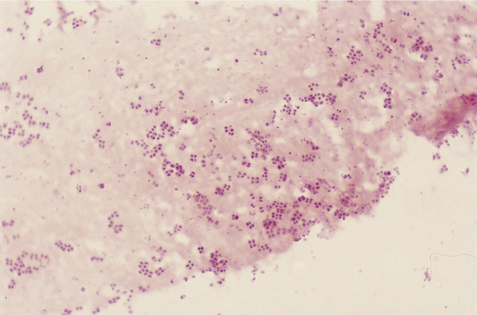

A cytologic examination of exudate from the ear of a patient with otitis externa should be performed during each examination. Samples can be taken with a dry, cotton-tipped swab placed as far into the canal as is comfortable and safe—usually to the junction of the vertical and horizontal canals. Obtained exudate is placed on a slide and mixed with mineral oil to examine for ear mites. A second sample should be rolled on a slide and stained with either a Wright-Giemsa stain, modified Wright-Giemsa stain, or Gram’s stain. If the exudate is greasy or waxy, heat fixation before staining may be helpful. The stained slides should be examined with the low- (100×) and high- (1000×) power objectives of the microscope. A low-power scan permits rapid evaluation of the smear and identification of the best area(s) of the slide for high-power examination. Otic parasites will be seen at low power (Figure 9-1). High-power oil immersion (1000×) evaluation permits quantitation of yeast and examination for bacteria.

The physical characteristics of the material collected from the external ear canal may provide clues as to the underlying cause. The normal ear canal should have small quantities of yellowish to light brown nonodiferous ceruminous discharge. Dark yellow to light brown discharge is seen in ears infected with gram-positive cocci. Pale yellow, thick, sweet, or sewer-smelling purulent exudates are noted in ears infected with gram-negative rods. Copious, dark brown, waxy, or “yeasty” smelling exudates are seen with the yeast Malassezia canis. Dark brown or black, crumbly exudate resembling coffee grounds suggests the presence of the parasitic mite Otodectes cynotis. A white exudate with no odor, resembling melted candle wax, is often seen after resolution of infection in cases of chronic otitis externa. There is no evidence cytologically of any microorganisms in this exudate, just continued excessive oily or waxy cerumen of hyperplastic ears. Combinations of the various etiologic agents lead to alterations of the characteristics listed previously.

The normal cytology of the external ear canal is characterized by the presence of squamous epithelial cells and low numbers of commensal but potentially pathogenic microorganisms, including M. canis and Staphylococcus intermedius. There is some debate as to whether M. canis is a primary pathogen; however, it is found three times more frequently in ears with otitis externa than in normal ears. M. canis is the most common organism demonstrated in ear specimens. It has been isolated in up to 49% of normal dogs and 23% of normal cats. In dogs, M. canis has been isolated in up to 80% of otitis externa cases and is probably the most common complicating factor of allergic otitis. In one study it was proven that M. canis in the presence of extraneous influences of atraumatic manipulation or moisture enhanced the conditions necessary for proliferation of the organisms and gross and microscopic evidence of otitis externa, establishing this organism as an opportunistic pathogen.2 On cytologic examination, there are usually few to no leukocytes unless bacteria are also present with the broad-based budding yeasts.

A semiquantitative cytologic evaluation of the exudate from normal ears and from ears with otitis externa in the dog and cat has been performed.3 In this study it was shown that numbers of cornified squamous cells are not consistently correlated with clinical findings, as animals with high counts may not show any clinical sign of otitis externa. In the above mentioned study, the results indicated that two or fewer M. canis yeast cells per high-power dry field (400×) should be considered normal in the dog or cat. Mean counts of greater than or equal to five yeast cells per high-power dry field in the dog and greater than or equal to 12 yeast cells per high-power dry field in the cat should be considered abnormally increased. It was theorized that Malassezia otitis may be a more common clinical entity in the cat than previously reported in the literature and that clinical signs are associated with higher mean yeast counts than in the dog.3

In reference to bacteria, mean counts per high-power dry field (400×) less than or equal to five bacteria per field in the dog and less than or equal to four bacteria per field in the cat should be considered normal, whereas mean counts greater than or equal to 25 bacteria per field in the dog and greater than or equal to 15 bacteria per field in the cat were abnormally increased.3 Degenerating neutrophils are seen most often with significant bacterial disease and may indicate the need for systemic antibiotic therapy.

The most common gram-positive organism isolated from cases of canine otitis externa is Staphylococcus intermedius (Figure 9-2). Other gram-positive bacteria isolated include Streptococcus spp., Micrococcus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium spp., and Bacillus spp. Gram-negative organisms isolated from cases of canine otitis externa include Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., E. coli, and Pasteurella spp. These gram-negative organisms, particularly Pseudomonas, are seen more commonly in chronic cases of otitis externa (Figure 9-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree