Chapter 10 MICROBIOLOGY AND DISEASES OF SEMEN

The acceptance of artificial insemination (AI) by some of the major equine breed registries has had a tremendous impact on the total population of mares that can be booked to a stallion in his lifetime. International movement of semen in a cooled or frozen state has made disease transmission across countries a real threat.1,2 Traditionally, the stallion has always been considered an important epidemiological risk factor in spreading venereal diseases. In Europe, North Africa, and some Asian countries, strict regulation of equine breeding through institutions such as national stud farms and remount stations has been implemented since before World War I in order to limit risk of disease outbreak, particularly Dourine.3 Today, with advanced technology and ease of transport of stallions, the same risk still exists. The high risk that the stallion poses to the mare population to which his semen is exposed becomes a more serious threat when we realize that the stallion is an asymptomatic carrier of most diseases.1,4

This chapter reviews the main epidemiological and clinical features as well as preventive measures for sexually transmitted infections in the equine. It draws primarily from a recent review by the authors.1,5 In addition, some of the most important diseases of semen (hemospermia and urospermia) are discussed.

BACTERIAL CONTAMINATION

Contaminant of the Surface of the Penis or Urethra

Many commensal bacteria (Box 10-1) including Escherichia coli, Streptococcus zooepidemicus, Streptococcus equisimilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus spp., Klebsiella spp., and Pseudomonas spp. are part of the exterior of the stallion penis, are not regarded as pathogenic, and may be cultured from an ejaculate or mare uterus.6 Alterations of the normal bacterial flora on the exterior genitalia may cause the growth of opportunistic bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus, which, if inseminated, may cause infertility in susceptible mares. P. aeruginosa has been isolated from penile swab with frequencies ranging from 20% to 40%.7–9

Box 10-1 Common Organisms Isolated from Stallions and Mares

Nonpathogenic Bacteria

S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and K pneumoniae are the most common isolates in cases of endometritis in the mare.5,6,10 Infections caused by P. aeruginosa or K. pneumoniae are often considered venereal because of the mode of transmission of these organisms (e.g., coitus, insemination with infected semen, genital manipulations).11–14 The capsule type of Klebsiella seems to be a determinant in which organism is involved in equine metritis. Capsule types K1, K2, and K5 are the most frequently associated with equine metritis. Capsule type K7 is thought to be part of the stallion’s normal preputial flora.15

The majority of stallions with disrupted microbial flora of the genital tract can shed pathogenic bacteria and are often asymptomatic carriers. The most common manifestation of this infection transmission is persistent mating-induced endometritis or infectious endometritis leading to reduction in fertility in susceptible mares. The factors that contribute to the colonization of the penis by pathogenic bacteria are not well understood. The intact penile skin and the normal desquamation of its cells help combat the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. However, frequent washing of the penis with soaps, detergents, and some antiseptics change the texture of the skin and will increase the susceptibility of the penis and prepuce to colonization by pathogenic organisms.16–18 Excessive cleansing of the stallion’s penis with detergents and antiseptics may also be responsible for severe balanitis and colonization by bacteria or fungus (Fig. 10-1). The environment in which a stallion is housed may influence the type of organisms harbored on the external genitalia. These organisms can also be acquired at the time of coitus with a mare that has a genital infection.

Treatment of stallions depends on the type of bacteria and method of breeding. For stallions breeding by AI, a thorough penile wash before semen collection is recommended. The filtered semen is then diluted with an extender containing the antibiotic for which the bacterial is sensitive and incubated for 20–30 minutes before use for insemination. Minimum contamination breeding technique (MCBT) is very helpful when natural cover is the only method of breeding.19 The mare’s uterus is infused with an antibiotic-containing semen extender just before mating. Stallions breeding by natural cover should be washed and scrubbed thoroughly. After washing, the penis is dried. Alternatively, the mare may be covered and then a uterine lavage performed followed by uterine infusion with appropriate antibiotic between 4 and 6 hours after breeding. However, it should be kept in mind that misguided or improper use of antimicrobials as uterine infusion or additive may pose a serious concern regarding multiresistant bacteria and development of fungal and yeast infection. Stallions with penile colonization by Klebsiella or Pseudomonas can be washed with a weak solution of HCl (0.2%) or sodium hypochlorite (bleach 5.25%), respectively.14,19 Systemic treatment with antibiotics should be avoided since it has proved unrewarding in most cases. Stallions with Pseudomonas infection have been reportedly treated with iodine-based surgical scrub followed by the application of 1% silver sulfadiazine cream daily for 2 weeks. Field observations from practitioners suggest that inoculation of penile surface with bacteria (smegma) from a normal stallion may be helpful in re-establishing the normal flora of the penis.

Bacterial Infection from the Accessory Sex Glands

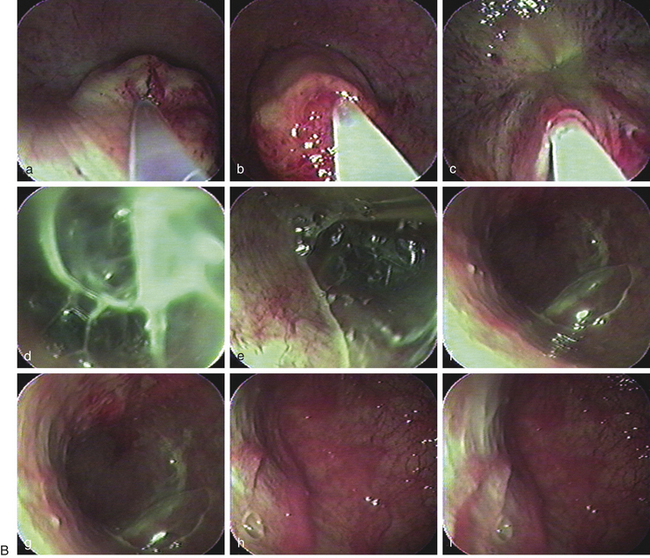

Bacterial seminal vesiculitis is the most common infection of the accessory sex gland in the stallion.20–23 Although not very common, this disease often results in serious economic losses because of its persistent nature, possibility for venereal transmission, and detrimental effect on fertility of both the stallion and mare. The most common isolates from cases of infectious seminal vesiculitis in the stallion are P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Proteus vulgaris and Brucella abortus.13,14,20,22–26 A case of seminal vesiculitis due to Acinetobacter calcoaceticus has been described.27 The infected stallions are usually identified initially by the presence of neutrophils in their ejaculates, pyospermia, hemospermia, sperm agglutination/precipitation, and poor motility along with a history of infertility or subfertility.12,20,23,28 Confirmation as well as treatment may be achieved by direct culture and infusion of the vesicular glands using endoscopy (Fig. 10-2).3,29 Direct sampling from the seminal vesicles can be obtained by videoscopy and catheterization of the ejaculatory duct.3,29–31 Treatment of seminal vesiculitis is often very difficult because the majority of antimicrobials cannot reach the gland in sufficient concentration.20,27,28 Broad-spectrum antimicrobials such as trimethoprim sulfa may be used systemically.28 Enrofloxacin has been reported to reach sufficient concentration in the seminal vesicles following parenteral administration.27 Direct flushing of and in situ infusion of the antimicrobial into the glands is the preferred method of treatment.3,21,22,29 Direct lavage of the vesicular gland with amikacin combined with oral treatment with trimethoprim sulfa for 8 days has been successful for treatment in a case of seminal vesiculitis caused by P. vulgaris.22. Infusion of an extender containing a specific antimicrobial in the uterus of a mare before breeding combined with post-breeding lavage helps prolong the survival of semen and control bacterial growth.13,20,27,32–36

Contagious Equine Metritis

The causative agent of CEM is a fastidious growing, micro-aerophilic, non-motile, gram-negative rod or pleomorphic coccobacillus known as Taylorella equigenitalis, which is not present in North America but is endemic in Europe. Efforts for eradicating the disease from the breeding industry have been successful, but CEM still occurs sporadically in some countries.15,37,38

All breeding stallions in countries with no surveillance system or stallions that are imported from countries where CEM is present should be tested prior to breeding during the quarantine. CEM-infected stallions are asymptomatic carriers and harbor the organism in the urethral fossa, the urethra, or the sheath. Diagnosis of CEM is made by culturing the organism from these sites as well as from semen.39,40 Transport medium is Amies supplemented with charcoal. Swabs are plated on Columbia blood-chocolate agar at 37°C and 7% carbon dioxide. Because of the slow growth of T. equigenitalis, the possibility of false-negative results is relatively high. It is estimated that a single clitoral swab would detect 95% of the carrier mares if infected more that 8 weeks earlier. Cervical swabs detect about 85% of the acutely infected mares and only 30% of chronically infected mares.

Another test that is commonly used is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, which appears to be very sensitive. However, because of the sensitivity of this test, an increase in the number of false positives may be present.41–45 There is also a risk that the test may reveal non-pathogenic strains.

Mares bred to infected stallions will develop a severe purulent vaginitis, cervicitis, and catarrhal endometritis, resulting in infertility and, rarely, abortion. These mares will appear to clean up but will remain infected, and the organism can be cultured from the clitoral fossa.39

Positive stallions must be removed from breeding, and treatment consists of daily washing of the penis and urethral fossa with 2% chlorhexidine gluconate followed by packing the areas with nitrofurazone (0.2%) ointment daily for 7 consecutive days.39,46 In countries where nitrofurazone cannot be used, a suitable alternative is enrofloxacin. Association of the local antiseptic treatment to systemic treatment with sulfamethizole trimethoprim (30 mg/kg) every 12 hours for 10 days.40 Treated stallions should be tested several times within 6 weeks after treatment before breeding. Two swabs must be obtained no sooner than 7 days after completing treatment with at least 2 days between cultures. Regular washing with chlorhexidine is not 100% efficacious for the prevention of CEM in stallions.47

In countries where mule production is important, veterinarians should be aware of a risk of CEM organisms in the jackass. A species of Taylorella has been isolated from donkey jacks in Kentucky and California.48–50 These asinine strains named T. asinigenitalis did not cause a CEM syndrome in mares bred naturally (Kentucky) or with shipped semen (California). However, experimental infection with the Kentucky isolate resulted in infection. T. asinigenitalis has been isolated recently from the genital tract of a 3-year-old Ardennes stallion with a natural infection.

Other Potentially Harmful Microorganisms

Other microorganisms that can be potentially transmitted venereally include Chlamydia spp. and Mycoplasma spp. Mycoplasma spp. have been isolated from the external genitalia and semen of clinically normal and infertile stallions, but their exact role in uterine infection is not well established.51–53 M. equigenitalium, M. subdolum, and Acholeplasma spp. have been associated with infertility, endometritis, vulvitis, and abortions in mares and with reduced fertility and balanoposthitis in stallions.51,54,55 M. equigenitalium and M. subdolum were isolated from the genital tract of mares (5%–34%) and aborted equine fetuses (7%); however, the occurrence of Mycoplasma spp. was not always correlated with reduced fertility.51,54–56

Genital chlamydiosis of horses has been reported to result in mild chronic salpingitis,57 reduced reproductive rates,58,59 low ejaculate quality,60 and occasionally abortion.61–64

Detection of chlamydial organisms from aborted equine fetuses ranges from 20% to 55%.64,65 However, these reported rates may be too high because other infections were present and it is difficult to culture this organism. Chlamydial organisms that have been found in the horse include Chlamydophila pneumoniae, equine biovar associated with respiratory diseases, and C. abortus and C. psittaci, which were both detected in equine abortion cases.63

VIRAL CONTAMINANTS

Although many viruses have the potential to be found in semen during the viremic phase of the disease, only equine arteritis virus (EAV) responsible for EVA and equine herpes virus III, the etiologic agent for equine coital exanthema are considered as sexually transmissible.66 The potential for the equine infectious anemia virus to be transmitted through semen has been suspected and is still a subject of debate.

Equine Arteritis Virus

EAV is a small RNA virus of the genus Arterivirus belonging to the family of Arteriviridae. EVA has a worldwide distribution except for Iceland and Japan.67–71 The virus is non-arthropod–borne and primarily transmitted from stallion to mare.72,73 Horizontal transmission from stallion to another via fomites or contaminated bedding is possible.74 Presently EAV is responsible for major restrictions in the international movement of horses and semen. Prevalence of seropositive stallions in some countries reaches 60%–80% of all stallions.15,72,75–77

The virus targets primarily the endothelium of the small blood vessels and macrophages. The incubation period is 3 to 14 days. The acute phase of the disease is characterized by fever (up to 41°C) and panvasculitis resulting in limb and ventral edema, depression, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, serous nasal discharge, palpebral periorbital and supraorbital edema, and edema of the ventral abdomen.39,68,69,78,79 The virus may cause abortion and has caused mortality in neonates. Stallions may show severe preputial and scrotal edema with variable effects on spermatogenesis and sperm quality.80,81 Experimentally infected stallions experience a necrotizing vasculitis in the testicles, epididymis, and accessory sex glands. Natural EAV exposure results in long-term immunity to disease. Mares and geldings eliminate virus within 60 days, but 30%–60% of acutely infected stallions will become persistently infected, temporarily or permanently shedding virus in the semen.68,69 Mares infected venereally may not show any clinical signs, but they shed large amounts of virus in nasopharyngeal secretions and in urine, which may result in the lateral spread of infection by the aerosol route.

Venereal infection does not affect fertility, but mares infected at later stages of gestation may abort. Identification of carrier stallions is crucial to control the dissemination of EAV. These animals can be identified by serological screening using virus neutralization test. If positive at a titer of 1:4, the stallion should be tested for persistent infection by virus isolation from the sperm-rich fraction of the ejaculate or by test mating. Shedding stallions should not be used for breeding or should be bred only to seropositive mares through natural infection or vaccination technique.68,78,82–86 Total spontaneous elimination of viral shedding has been reported in some stallions.87

Abortion is one of the greatest risks of EAV infection. In cases of natural exposure, the abortion rate has varied from less than 10% to more than 60% and can occur between 3 and 10 months of gestation.76,88,89 Abortion is due to a severe edema and necrosis of the endometrium leading to placental detachment.68,69 The abortions appear to result from the direct impairment of maternal-fetal support and not from fetal infection.

Although mares and geldings are able to eliminate virus from all body tissues by 60 days after infection, 30%–60% of stallions become persistently infected. In these animals, virus is maintained in the accessory organs of the reproductive tract, principally the ampullae or the vas deferens, and is shed constantly in the semen. The development and maintenance of virus persistence is dependent on the presence of testosterone.90 Persistently infected stallions that were castrated but were given testosterone continued to shed virus, whereas those administered a placebo ceased virus shedding. Furthermore, stallions treated with an anti-GnRH product stopped shedding the virus during the treatment period but resumed within a few weeks after treatment ceased.87 Three carrier states are known in the stallion: (1) short-term during convalescence, (2) medium-term (lasting for 3–9 months), and (3) chronic shedder, which may persist for years after the initial infection. Virus shedding in mares and geldings is limited to the convalescence state.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree