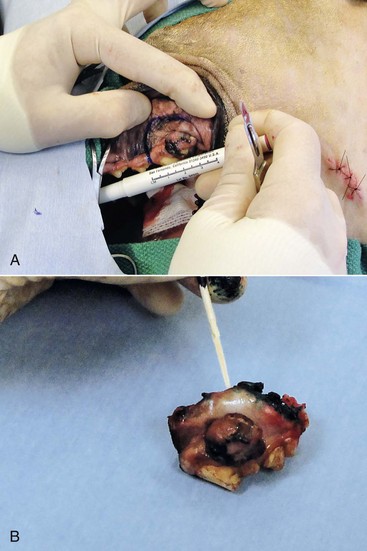

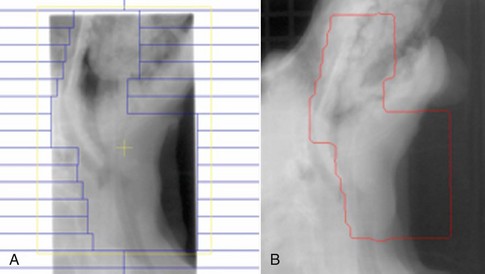

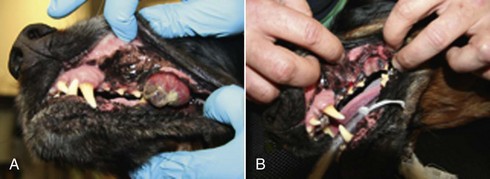

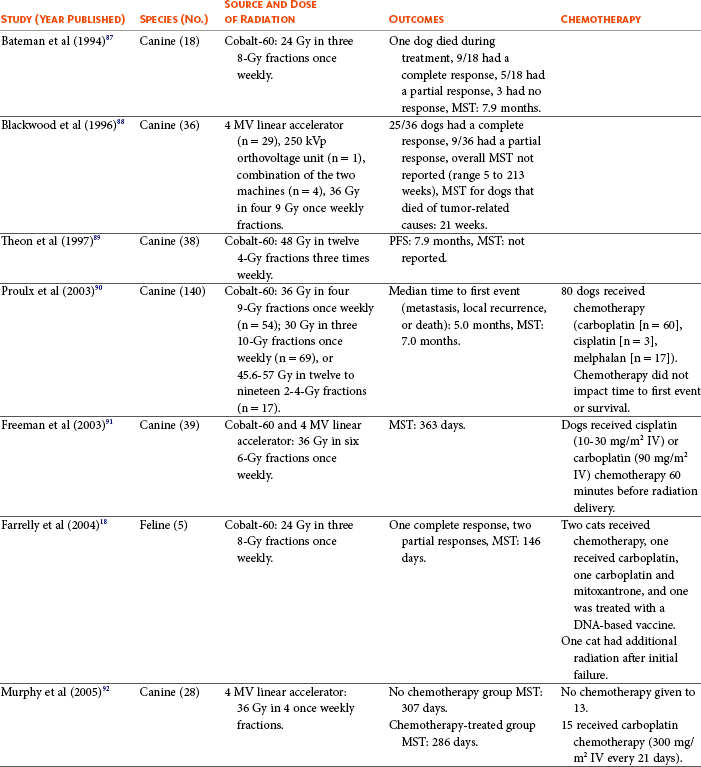

19 Melanoma is a relatively common cancer of dogs, especially those with significant levels of skin pigmentation. Melanomas in cats are relatively rare. The most common location for canine malignant melanomas (CMMs) is the haired skin, in which they grossly appear to be small brown-to-black masses but can also appear as large, flat, and/or wrinkled masses.1,2 Primary melanomas also can occur in the oral cavity, nail bed, footpad, eye, gastrointestinal tract, or mucocutaneous junction.3 Ocular melanomas of dogs and cats represent a distinct clinical syndrome and are discussed in Chapter 31. Metastatic sites can be varied, including local draining lymph nodes, the lungs, liver, meninges, adrenals, and other miscellaneous sites. Melanoma arises from melanocytes, which are the cells that generate pigment through the melanosome by a number of melanosomal glycoproteins. In humans, cutaneous melanoma can arise due to mutations induced by repeated, intense exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light (e.g., frequent tanning or working outdoors). Melanoma is currently the most rapidly increasing incident human cancer.4 Significant recent research into the etiology of human melanoma suggests multiple causes that are independent of the aforementioned UV-associated mutagenesis.5 Since most breeds of dogs have a hair coat that likely affords them protection from sunlight, UV-associated melanoma is less likely as a primary causative agent in the dog. However, pigment cells divide every time there is injury to the skin or if there is constant trauma (e.g., areas where dogs scratch or lick). Nevertheless, risk factors for canine melanoma are not well established. The most common oral malignancy in the dog is melanoma.2,3,6,7 Oral melanoma is most commonly diagnosed in Scottish terriers, golden retrievers, poodles, and dachshunds.2,8 Oral melanoma is primarily a disease of older dogs without gender predilection but may be seen in younger dogs.8–10 Additional oral tumor differentials include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), fibrosarcoma, epulides/odontogenic tumors, and others.2,3,7,11–13 Melanomas in the oral cavities of dogs are found in the following locations by order of decreasing frequency: gingiva, lips, tongue, and hard palate. Feline melanoma is relatively rare but appears to be malignant in most cases.3,14–21 Melanomas in dogs have extremely diverse biologic behaviors, depending on a large variety of factors. A thorough understanding of these factors helps the clinician to delineate in advance the appropriate staging, prognosis, and treatments. The primary factors that determine the biologic behavior of an oral melanoma in a dog are site, size, stage, and histologic parameters.8–10,22,23 Unfortunately, even with a comprehensive understanding of all of these factors, there are melanomas that have an unreliable biologic behavior; thus there is a need for additional research into this relatively common, heterogeneous, and frequently extremely malignant tumor. Melanomas can be difficult to diagnose pathologically in some situations, especially anaplastic amelanotic melanomas, which can masquerade as soft tissue sarcomas.24,25 Numerous investigators have attempted to increase the precision of identification of melanomas predominantly through immunohistochemical means.25–29 This identification can be accomplished through the use of multiple immunohistochemical assays on suspected melanoma tissue or through the use of an immunohistochemical cocktail of antibodies. The use of PNL2 and tyrosinase, beyond the typical use of Melan A and S100, appears to hold particular promise.30,31 The molecular characterization of canine and feline melanomas remains comparatively attenuated compared to the more comprehensive evaluation of human melanomas.32 BRAF is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which is commonly mutated in human cutaneous melanoma.33 However, BRAF mutations are uncommon in canine oral malignant melanoma,34 suggesting that certain canine and/or feline malignancies can have similar molecular signatures in addition to their already well-known clinical similarities in the context of resistance to chemotherapy and irradiation and similar variable sites of metastatic propensity. A number of investigators have reported a variety of molecular abnormalities or associations in canine and feline melanoma.35–52 The anatomic site of melanoma is highly, although not completely, predictive of local invasiveness and metastatic propensity. Melanomas involving the haired-skin that are not in proximity to mucosal margins often behave in a benign manner.1,3 Surgical extirpation is often curative, but histopathologic examination is imperative for delineation of margins, as well as a description of cytologic features. The use of Ki67 immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been reported to more reliably predict potential malignant behavior compared to classic histology for cutaneous melanoma.53 Oral and/or mucosal melanoma has been considered an extremely malignant tumor with a high degree of local invasiveness and high metastatic propensity.2,8–10,22,54 This biologic behavior is similar to human oral and/or mucosal melanoma.3,55 Two recent studies have called this dogma into question and suggest benign oral melanomas can occur more frequently than previously published.56,57 Caution is necessary when assessing histopathologic descriptions, suggesting a benign course for oral melanoma. The first author has managed approximately 20 dogs over the last 7 years presenting with florid systemic metastases with an original histopathologic report, suggesting an expectation for a benign clinical course based on a high degree of differentiation. Similar to cutaneous melanoma, Ki67 appears to hold prognostic importance in canine oral melanoma as well.58 Anatomic sites of intermediate prognostic significance between the generally benign-acting haired-skin and the often malignant and metastatic oral/mucosal melanomas in dogs include the digit and footpad. Dogs with melanoma of the digits without lymph node or distant metastasis treated with digit amputation are reported to have a median survival time (MST) of approximately 12 months, with 42% to 57% alive at 1 year and 11% to 13% alive at 2 years.59,60 Unfortunately, metastasis from digit melanoma at presentation is reported to be 30% to 40%,59,61 and the aforementioned outcomes with surgery suggest that subsequent distant metastasis is common even when no overt metastasis is found at presentation or digit amputation. The prognosis for dogs with melanoma of the footpad has not been thoroughly established; the first author (PJB) has found this anatomic site to be anecdotally similar in metastatic propensity and prognosis to digit melanoma. Interestingly, human acral lentiginous melanoma (plantar surface of the foot, palms of the hand and digit) has an increased propensity for metastasis.62 A thorough review of prognostic factors in canine melanocytic neoplasms has been recently published.63 This review took a regimented, systematic approach to analyzing published reports to date in order to identify those factors that appear to be repeatable and statistically defensible, while also identifying areas in which additional work is necessary due to incomplete data. For those veterinary clinicians and/or researchers interested in canine melanoma, this publication cannot be more strongly recommended. Tables 1 and 2 from this report are particularly useful in estimating prognosis for a specific patient and subsequent identification of the most logical treatment options. For dogs with oral melanoma, primary tumor size has been found to be prognostic. The World Health Organization (WHO) staging scheme for dogs with oral melanoma is based on size and metastasis and is summarized in Box 19-1. MacEwen and colleagues reported MSTs for dogs with oral melanoma treated with surgery to be approximately 17 to 18 months, 5 to 6 months, and 3 months for stage I, II, and III disease, respectively.9 More recent reports suggest stage I oral melanoma treated with conventional therapies, including surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy, have MSTs of approximately 12 to 14 months, with most dogs dying of distant metastatic disease rather than local recurrence.64,65 Other investigators have found dogs with stage I oral melanoma to have median progression-free survival (PFS) times of 19 months, similar to the original MacEwen et al report.66 The staging of dogs with melanoma is relatively straightforward. A minimum database should include a thorough history and physical examination, complete blood and platelet count, biochemical profile, urinalysis, three-view thoracic radiographs, and local lymph node aspiration with cytology, whether lymphadenomegaly is present or not. Williams and Packer reported that approximately 70% of dogs with oral malignant melanoma had local lymph node metastasis when lymphadenomegaly was present, but more importantly, approximately 40% had local lymph node metastasis when no lymphadenomegaly was present.67 Additional considerations should be made for abdominal compartment testing (e.g., abdominal ultrasound) in all cases of CMM, especially in cases with moderate-to-high metastatic anatomic sites such as the oral cavity, feet, or mucosal surface of the lips, because melanoma metastasizes to the abdominal lymph nodes, liver, adrenal glands, and other sites. The use of sentinel lymph node mapping and lymphadenectomy is of diagnostic, prognostic, and clinical benefit in human melanoma.68 Relatively few investigations have been reported to date for sentinel lymph node mapping and/or excision for dogs with malignancies,69–73 and we strongly encourage additional investigation in this area. Furthermore, the use of novel staging modalities such as gallium citrate scintigraphy is also encouraged.74 Surgery continues to be the most effective local treatment modality for melanoma, and early detection is often necessary for a successful outcome. Tumors in the caudal aspect of the oral cavity are often large by the time they are diagnosed relative to rostral tumors; therefore it is more difficult to obtain complete surgical excision. Gross characteristics of melanomas raise suspicion for the diagnosis, and pigmented melanomas can be easily confirmed via fine needle aspiration and cytology. In dogs, small (<2 cm), mobile, well-circumscribed, slow-growing cutaneous melanomas tend to be benign and easily excisable, whereas large, poorly defined, ulcerated, and rapidly growing tumors can make surgical excision difficult. In the latter example, incisional biopsy and IHC can be an important part of the diagnostic work-up, particularly if the mass is nonpigmented and the diagnosis of melanoma is in question. In cases for which lymph node cytology results are equivocal (e.g., difficulty distinguishing between melanophages and melanoma cells), lymph nodes should be surgically excised and submitted for histopathologic evaluation (which includes IHC). Enlarged lymph nodes are often associated with metastasis, particularly with advanced tumors or tumors of high grade, and nodal effacement is common (Figure 19-1). Figure 19-1 Excisional biopsy being performed on the popliteal lymph node from the dog in Figure 19-6. Note the effaced node overtaken with pigmented cells and the smaller nodule within the lymphatic vessel slightly distal to the node (toward the right in the photograph). Benign cutaneous tumors are typically completely excised with 1-cm skin margins (and ideally one fascial plane deep). Partial mandibulectomy and maxillectomy are usually required for complete removal of oral melanomas arising from the gingiva or from other oral mucosa in close proximity to bone.75 A common error is to “shave off” a gingival mass simply because bone invasion is not observed. Due to the close proximity of the gingiva to the underlying bone, this approach typically leaves residual microscopic disease that leads to local recurrence (Figure 19-2). Advanced imaging (i.e., computed tomography [CT] scans or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is critical for assessment of tumor extent and potential bone involvement. It is also helpful in the detection of enlarged regional lymph nodes (e.g., medial retropharyngeal nodes) that are difficult to palpate. Some tumors do occur in mucosal areas that are not adjacent to bone (e.g., buccal mucosa) or originate in the lip (Figure 19-3) or tongue (Figure 19-4) and are amenable to excision of the soft tissues only. The location of the tumor dictates the type of partial maxillectomy (i.e., premaxillary, unilateral rostral, central, or caudal) that is required. Complete excision of oral tumors has been shown to significantly impact prognosis.76 Dogs with tumor cells extending to the peripheral margin were 3.6 times more likely to die from tumor-related causes compared to dogs for which margins were considered complete. In that same study, dogs with tumors caudal to premolar number three (PM3) were 4.3 times more likely to die from tumor-related causes compared to dogs with tumors located rostral to PM3. For small caudal tumors lateral to the dental arcade (Figure 19-5), an oral approach provides enough exposure/access for complete excision; however, large tumors of the caudal maxilla or small tumors that extend medial to the dental arcade are best treated via a combined dorsal and intraoral approach.77 The combined approach maximizes the surgeon’s ability to obtain wide margins on tumors involving the caudal hard palate and inferior orbit. For small, superficial melanomas associated with the mandible, partial mandibulectomy is typically sufficient78; however, for large tumors that show evidence of intramedullary extension, consideration should be given to a subtotal or complete hemimandibulectomy. Local recurrence rates vary from 22% following mandibulectomy to 48% after maxillectomy75,79 and the MST for dogs treated with surgery alone varies from 150 to 318 days, with 1-year survival rates less than 35%.28,75,76,78–81 There are few objective data available to guide decision making for surgical margin width. Given the invasive nature of malignant melanomas, wide margins (2 to 3 cm) are optimal whenever possible; however, for oral lesions, wide margins are often not possible due to the limited amount of surrounding normal tissues. In the author’s experience, 1 to 2 cm margins are usually adequate for complete excision of malignant tumors with well-defined borders (Figures 19-5 and 19-6). As with any oral tumor, inspection of the gross tumor borders must be interpreted along with diagnostic imaging to determine resectability and resection lines. Wider margins are usually possible with digital melanomas because digit amputation can often be performed at a level several joints above the proximal extent of the tumor. Figure 19-6 Malignant melanoma in the webbing between digits 3 and 4 (same dog as in Figure 19-1). Surgical margins were between 1 and 2 cm beyond the tumor edge. Excision was complete in this case. With the widespread access to advanced imaging and improvements in surgical techniques (e.g., combined dorsal and intraoral approach for caudal maxillary tumors) and surgical oncologic training, complete tumor excision is more likely to be achieved. The surgical goals should be driven by the tumor stage, its location, and the surgeon’s ability to perform a wide resection in locations where surgery is difficult (e.g., large caudal tumors). Unplanned or limited attempts at excision should not be made because the first chance to operate is the best chance to achieve tumor-free margins. For patients that undergo surgical excision, quality of life is usually very good and most dogs resume eating in the first day or two following surgery. Further, owner satisfaction with functional and cosmetic results following mandibulectomy and maxillectomy is high.82 The functional outcome of single digit amputation is excellent and partial foot amputations (requiring excision of more than one digit; see Figure 19-6) are also tolerated very well and result in a good functional outcome.83 For tumors that are not amenable to wide excision or result in incomplete margins via histopathologic assessment, the combination of surgery and radiation or surgery plus adjuvant therapy should be considered. Historically, surgery has not been recommended when metastatic disease has been documented (e.g., a positive lymph node is discovered during tumor staging). However, the role of adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or immunotherapy) in conjunction with cytoreductive surgery is being investigated for human metastatic melanoma and such approaches are now being explored in dogs (covered elsewhere in this chapter).84–86 Radiation therapy plays an important role in the management and treatment of canine and feline oral melanomas. As with most tumor types, radiation therapy is used for the purpose of achieving local or regional control of the tumor. Radiation therapy has been described as both a primary and adjuvant therapy and both hypofractionated and definitive protocols have been used (Table 19-1).87–92 Table 19-1 Published Studies on the Treatment of Oral Melanoma with Radiation Therapy MST, Median survival time; PFS, progression-free survival; IV, intravenous. Melanoma is thought to be a relatively radioresistant tumor type often necessitating a higher dose in each fraction to achieve local control, although this point is somewhat controversial.93 Most protocols used in dogs and cats have pursued higher dose per fraction protocols accordingly, although the relative radiosensitivity of melanoma in companion animal species has not been determined. Hypofractionated protocols have the advantage of fewer treatments with fewer anesthetic episodes, lower cost, and less time commitment for the owner. These protocols in general also result in less severe acute effects. The main disadvantage of hypofractionated protocols is a lower overall and biologic equivalent dose, which results in lower rates of local control and an increased risk for late side effects. For a discussion of side effects, see the section on radiation side effects later in this chapter and in Chapter 12. Treatment planning can be done manually or can be planned by computer to allow a more conformal and homogeneous dose distribution with better sparing of normal tissues. Most studies have reported using at least a 2-cm margin around the tumor bed or surgical incision site. The field can be shaped by using manual blocking or, if available at the treating facility, a multileaf collimator (Figure 19-7). The reported range of partial and complete responses to radiation therapy are 25% to 31% and 51% to 69%, respectively, yielding an overall response rate of 82% to 94%.87,90,92 When treating gross disease, responses are generally rapid, and dramatic decreases in tumor volume can be seen within several weeks of starting therapy (Figure 19-8). PFS has been reported to range from 5 to 7.9 months.89,90 Reported recurrence rates after radiotherapy vary and are confounded by different radiation protocols and adjuvant therapies used in these studies. Proulx et al reported a local recurrence rate of 26% when treating microscopic disease after incomplete surgical resection and radiotherapy and 45% for dogs treated with radiotherapy for macroscopic disease.90 The reported MSTs for dogs treated with radiotherapy range from 5.3 to 11.9 months (see Table 19-1).87,90–92 The majority of these studies are retrospective and use a variety of radiotherapy equipment, protocols, and adjuvant therapies, making it difficult to determine an ideal treatment regimen. Reported protocols include 2 to 4 Gy fractions daily for 12 to 19 treatments, 4 Gy per fraction 3 times weekly for 4 weeks, 8 Gy per fraction once weekly for 3 treatments, and 9 Gy per fraction once weekly for 4 fractions. Farrelly et al reported five cats that were treated with radiotherapy for oral melanoma.18 There was one complete response and two partial responses with a MST of 146 days. One cat was treated with carboplatin, and one cat was treated with carboplatin and mitoxantrone, in addition to the radiation protocol. Another cat in this study was given a DNA-based vaccine as adjuvant to radiation.

Melanoma

Pathology and Molecular Biology

Biologic Behavior and Prognostic Factors

Size and Stage

Staging

Treatment

Radiation Therapy

Outcomes of Dogs and Cats Treated with Radiation Therapy for Oral Melanoma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine